Source Feed: Walrus

Author: Carmine Starnino

Publication Date: May 8, 2025 - 13:10

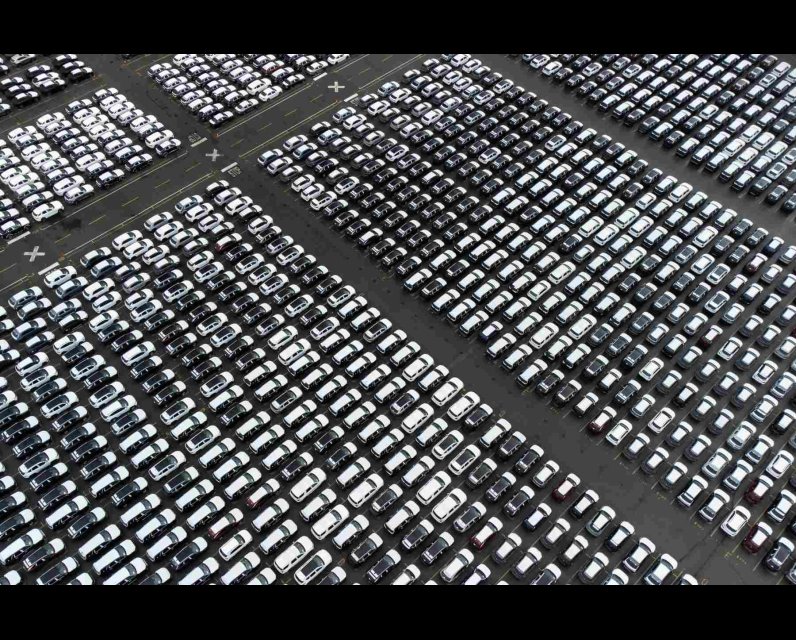

The Economy Is One Tariff Away from a Supply-Chain Meltdown

May 8, 2025

Flavio Volpe is one of those rare people who can make trade policy sound like a contact sport. As head of the Automotive Parts Manufacturers’ Association, he’s become one of Canada’s most vocal and effective industry advocates. In 2022, when protesters blocked the Ambassador Bridge—cutting off a billion dollars in daily trade—Volpe stepped in, securing a court injunction that reopened the vital link. Then there’s Project Arrow, his boldest initiative yet: a fully Canadian, zero-emissions concept vehicle unveiled in 2023, designed to showcase what this country’s auto sector can do. But it’s his fight over US tariffs that’s put him at the centre of a high-stakes economic debate. Volpe has pushed back—hard. He rallied industry leaders to speak out on the real-world impacts, emphasizing the risk of layoffs and supply-chain disruptions on both sides of the border. Much of his attention in recent weeks was focused on stopping tariffs on Canadian auto parts, scheduled to kick in May 3. That danger has receded; parts that meet the Canada–United States–Mexico Agreement are exempt—at least for now. I called Volpe, over Zoom, to talk about the stakes for Canadian manufacturing, his strategy, and what happens when politics and production lines collide.

Congratulations on winning the parts exemption. Can you explain why the panic around this specific tariff was so intense?

It’s a partial win, at best. The 25 percent blanket tariff on all car imports to the US still stands. But yes, we got relief on the bigger threat on auto parts. Why bigger? Because on parts, you’ve got 1,000 fail points. Meaning, you’ve got 1,000 suppliers who operate at razor-thin margins of 6 or 7 percent. If they’re told by their customer that they’ve got to eat a 25 percent duty, there’s no point in making anything. They’re done. A tariff on parts—and you can quote me swearing, I don’t care—will fucking crash the industry.

Break it down. How?

Automakers can try to absorb the import tariff, because it’s not on all their vehicles. They’ve managed to spread the cost across both domestic and imported vehicles. Every year, about $125 billion worth of cars flow into the US from Canada and Mexico. Slap a 25 percent tariff on that, divide it over 250 production days, and you’re looking at $125 million a day in added costs. And somehow, the automakers have been eating it. Some, who have stronger balance sheets, haven’t adjusted the prices, because they think, “Oh, this is going to be temporary. It might be a week, might be a month, might be three months. I could price that in now on any units I move, and the impact might be a couple of thousand dollars per vehicle”—which, by the way, is your entire profit. But if you know it’s short term, especially if you can survive and your competitor doesn’t, then survival of the fittest means you might have access to greater market share after.

But on parts, it’s different. That’s a twenty-four-hour inventory system, just in time. On cars, you could spread the tariff out across other inventory you have in the lots. Usually, dealers have two to three months of inventory, sixty to ninety days. You can try to absorb it. You can’t do that on parts. The seat that you’re buying in London has to go into a Jeep in Ohio. It’s bought today and installed tomorrow. If it’s not installed tomorrow, it’s installed the day after. And if you have to absorb the tariff in producing that seat, you stop making it. But as a car manufacturer, you can’t make a car without all of the parts. If I have a Jeep without seats, I don’t have a Jeep. And if I don’t have a Jeep today, I’m not going to schedule production tomorrow. So don’t send me the wheels. Don’t send me the engines. Don’t send me the screens.

It’s all connected.

Yes. When the Ambassador Bridge was blockaded, it took two days for plants from Ontario to Kentucky to get shut down, and they shut down for five days. I had to go to Ontario Superior Court, as the plaintiff, seeking an emergency injunction. I had to argue irreparable harm. In that case, I successfully argued a billion dollars in lost production, and they gave us the injunction. My point was that the blockade wasn’t something we could figure out in a couple months. The car companies would be dead in a couple months.

What you’re describing is a situation where the supply chains are so heavily integrated that the lights start going off everywhere.

A lot of people say I’m an alarmist. But that’s not how this works. It’s math. You’re going to run out of money, or you’re going to run out of time. Likely, you’re going to run out of time and money. A couple of weeks ago, every single association in the auto sector in the US co-signed a letter saying, “Don’t go forward with these tariffs on parts.” Amongst all the other risks, all it takes is one supplier to cause an automaker’s production to be shuttered. You cannot sell product at a 15 or 20 percent loss every day out of a greater cause. There’s no greater cause in automotive. We aren’t feeding hungry kids in Africa. We’re making a product for a discretionary purpose, a discretionary purchase.

Again, it’s not just reduced orders or factory slowdowns or layoffs. It’s a system-wide crash, even if one supplier can’t deliver in the entire chain?

Pick whatever product classification you want. If any one of those suppliers isn’t able to deliver, it stops all the other suppliers from delivering. We know this is true because we saw it during the pandemic. It was covered widely on the semiconductor shortage. We saw North American automotive production dip in 2022 while we had a chip shortage for probably five or six quarters. Why? Because during the pandemic, we stopped making cars for sixty days, which never happened before. Most of the automakers called their suppliers and said we’re not taking delivery of anything. That meant they also didn’t take delivery of microchips. But what else happened during the pandemic? The whole world got online, and the crushing demand for electronic products meant that the chip makers kept manufacturing. They just found new customers. So when automakers came back, chip makers were like, wait in line. And the automakers had no choice, so production dropped almost immediately. If I can’t get chips in these cars. I don’t have a car.

The argument from the Trump side is that he wants to move factories and jobs back to the US.

Right, but remember that the other half of the Canadian industry is based around Toyota and Honda. I don’t remember anybody in Tokyo and Nagoya saying let’s check with Washington before we build our companies. These were never American jobs is my point. Trump constantly says he wants to bring manufacturing back. The US used to make Nikes. So are they going to make shoes again? Are they going to hire their own eight-year-olds to stitch running shoes together? Is that where prosperity is at? The American lifestyle of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century is accommodated by access to Walmart, and Walmart drives prices down, so the cost of living is down. But the Walmart model drives sourcing to the lowest-cost jurisdiction. We created the China that we’re now fighting against.

Let’s assume, to be generous, that the Trump people all know this. Why are they doing it?

It’s a cult. They’ve surrendered all reason. Fanaticism for Trump has also whipped up a voting bloc that scares Republicans and his own cabinet members. It doesn’t help that he’s surrounded by people who don’t know things, like Peter Navarro, who has pitched car tariffs as a silver bullet. Let me be generous. Navarro is articulate, but he articulates arguments with lies and then, using the gravity of the office, pushes those lies out.

The situation you’ve just described seems like insanity. On some level, are you trying to intuit a strategy here? Are you trying to make sense of what doesn’t make sense?

I’m using realpolitik. I am speaking strategically about something that’s insane, because, number one, we don’t have the leverage to be insane ourselves. We’re in a marriage that we can’t get out of. It’s toxic. The reason we can’t leave this marriage is—well, physically we can’t. We’re here: the end. We can’t ship our parts out. From a commercial point of view, there’s no opportunity on the ocean. The ocean eats the profit from manufactured goods. Unless your manufactured goods are made in a place that suppresses the cost of labour anywhere from 90 percent to 100 percent. Unless you don’t have to worry about any of the environmental concerns we have. Unless you’re able to rally all the resources of a jurisdiction into the sole objective of winning market share, even if you have to buy it around the world. That’s the only way to make it work: suppress costs, ignore consequences, and marshal every resource toward one goal. Obviously, I’m describing China.

We don’t have any of that, so we have no choice but to be strategic in the face of insanity. And it may not work, but I use the analogy of being locked in a cage with a tiger. The tiger will eat you. But if you freak out, you’re just going to speed that up.

Where do you see Canada’s automotive industry in four years?

In many ways, it relies on Americans. We’re not in a vacuum. Trump is trying to break the Canadian automotive industry, yes, but he’s also trying to break everything—he’s trying to break all the industrial conventions in the US and all the political conventions. He’s infringing on individual rights, but also on congressional and state jurisdictions. He is creating real grievances throughout society. Republicans are starting to open their mouths, like the four who supported Senator Tim Kaine’s resolution to terminate Trump’s economic-emergency declaration on Canada, which was used to justify new tariffs. There are also enough people—others in the billionaire class—who have built up their own empires and don’t really care about Trump. The best thing to do right now, they’ve probably decided, is to go along with him. But wait till their money gets hurt.

My question still stands. In four years, will we still build cars here?

Yes. And the reason is math. We buy more cars than we build. General Motors, for example, sells 300,000 cars here. Most of them come from the US, but we have the capacity to make as many in Oshawa and Ingersoll. Same thing with Ford. Canadians like F-150 pickup trucks. How many are you going to sell? Well, you probably sell 75,000 here. There was a big story recently about how Honda was going to move. But why would they move? Nearly 70 percent of what Honda makes here gets sold to Canadians. That’s a really good example of build where you sell. As an industry, we have to focus that way. If the world is going to move away from globalization into regionalism and, with big enough markets, nationalism, we can absorb a lot of that demand locally—if we work together with automakers here. And I’m going to say something other people are not talking about: this is a time to think about Canadian automakers. We have the technology, and we have the people. We proved it with our own project.

You mean Project Arrow.

We built it as a demo. But every single part of that car, including the screens, we got locally. Look at the Mexicans. The government is launching the Olinia, an EV company that’s going to sell a low-cost mini electric vehicle to Mexicans who can’t afford foreign cars. The Olinia is, in essence, an electric quadricycle that presents like a smart car, to be sold for $10,000. Part of their solution for demand in Mexico will be: we’ll build it ourselves. Turkey’s done it. Vietnam has done it. If Canada is going to continue to invest in its automotive sector, which is a clustering of the most technology in the highest-priced consumer good on the planet, then we need to do things differently. Look, this isn’t really about Project Arrow. Project Arrow is our John the Baptist—the one clearing the path, announcing what’s coming. It says: this is what you can do, where you can do it, and who your partners can be. The government doesn’t have to do the legwork on whether it’s technically feasible or whether we have the people. We know it’s feasible. We have the people. Now get them together in an effort to see if we can’t make something Canadians will buy. Maybe they won’t. But god damn it, give it a shot. The post The Economy Is One Tariff Away from a Supply-Chain Meltdown first appeared on The Walrus.

The Toronto Blue Jays' visit to Seattle comes as fewer Canadians travel to the U.S. amid President Donald Trump's tariffs and threats of making Canada the 51st state. April saw a 51 per cent drop in cars with B.C. licence plates heading into the U.S. from southwest B.C. compared to the same month last year.

May 9, 2025 - 21:18 | | CBC News - Canada

The initiative has many people, including residents, business owners in affected communities and local governments, expressing some serious concerns.

May 9, 2025 - 21:18 | Klaudia Van Emmerik | Global News - Canada

'I feel really fortunate that Gabe was able to be there with our little brother because we know he would have been scared and he always needed somebody to feel that comfort.'

May 9, 2025 - 20:57 | Sarah Komadina | Global News - Canada

Comments

Be the first to comment