Deportation hearing for alleged Mafia boss in Canada derailed by wiretap decision

In the middle of a high-stakes deportation hearing against an alleged Mafia boss living in Canada, the government unexpectedly declared it will no longer rely on any evidence obtained from controversial Italian police wiretaps covertly made using the phones of visiting members of a mob family to Canada.

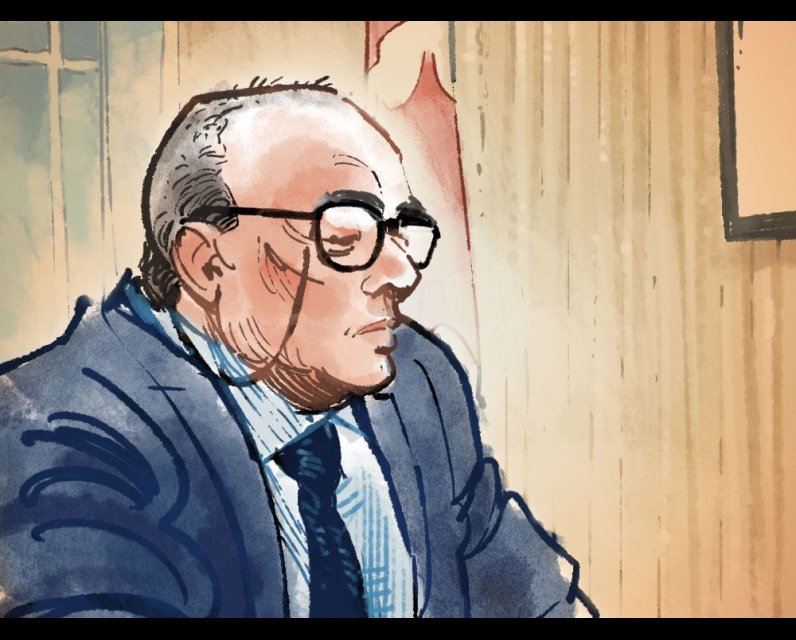

The announcement Friday threatens to derail yet another attempt to deport Vincenzo (Jimmy) DeMaria, a man accused of being a Mafia boss in Ontario who has successfully fought off deportation for more than 40 years.

An Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB) hearing is underway on the government’s latest attempt to deport DeMaria based on allegations he is a member of the ’Ndrangheta, the proper name of the powerful Mafia that formed in Italy’s region of Calabria. DeMaria has denied the allegation.

Lawyers for DeMaria had repeatedly called for the Italian police wiretaps to be rejected, calling them illegal foreign interference. On Friday, however, they said the government’s sudden agreement in the middle of the hearing was absurd.

“What we have here is an abuse of process by the minister (of public safety),” said Shoshana Green, one of DeMaria’s three lawyers at the hearing.

“It is an absurdity that the minister, on a whim, is changing the nature of this entire hearing. How can Mr. DeMaria properly prepare for a matter when they are literally changing the foundation of their case four days in?”

Green said information from the wiretaps has already been extensively “co-mingled” with other evidence entered in the case over years, including in two days of testimony earlier this week by a senior police officer from Italy who was the government’s first witness at this hearing against DeMaria.

Green asked Benjamin Dolin, the IRB member deciding the matter, to issue a stay of proceedings, which would suspend the government’s appeal of an earlier immigration board decision to allow DeMaria to remain in Canada , where he has lived since moving from Italy as an infant.

“Or in the alternative, we would certainly consent to the minister abandoning their appeal,” Green said.

Andrej Rustja, arguing on behalf of Canada Border Services Agency, said that after reviewing its strategy for the case Thursday night, the government decided to not rely on the wiretaps recorded by Italian police in Canada in 2019 and told DeMaria’s lawyers as a courtesy and to save time at the hearing.

Neither Rustja nor government lawyer Daniel Morse said why they shifted their strategy.

Dolin told Green the government’s change “would seem to benefit” her client. “I don’t see any prejudice to Mr. DeMaria,” but he adjourned the hearing to allow DeMaria’s lawyers to file a written motion for a stay and for the government to respond.

DeMaria had been scheduled to testify in the case Friday morning.

The Italian wiretaps have been under scrutiny for years.

The recordings provided an intriguing and colourful peek into activities of the ’Ndrangheta and revealed links between those under investigation in Italy to alleged affiliates in Canada.

In 2019, Italian police learned that a mobster in Calabria named Vincenza Muià was coming to Toronto to speak with people here to find out who within the ’Ndrangheta had murdered his brother in Italy, so that he could properly avenge his death.

Muià said he needed to be 100 per cent certain before enacting his vicious retribution for his dead brother because of organizational volatility. He wanted to check with DeMaria and other alleged ’Ndrangheta bosses in Canada about it, according to Italian police testimony heard earlier .

In one recording, according to a transcript translated into English, Muià told a Canadian who was travelling between Toronto and Calabria to tell “Jimmy” (who police identified as meaning DeMaria): “For my brother, once I know who it was, if I can, I’ll eat him in pieces, in pieces, but I have to be sure…. I’ll eat him in small pieces, small pieces on the barbecue, and I invite him to come eat.”

Police could listen to Muià’s plotting because they inserted a Trojan house virus into his phone that turned it into a microphone — recording not just what was said in phone calls but all sound in the room where the phone was, even when it was not in use.

The recordings are controversial because while the bugging was approved by an Italian judge, there was no judicial authorization by a Canadian court for communications to be intercepted in Canada when Muià visited, bringing his bugged phone with him.

The hearing heard this week that Italian police had asked police in Canada to help them bug the airplane that the visitors were arriving and departing on so they could hear what they said during the flights.

The Italian authorities were told by Ontario prosecutors that intercepting such communications in Canada without judicial authorization was illegal. While Canadian police helped Italian police retrieve a listening device that had been installed in Italy on an Alitalia jet once it landed in Toronto, they refused to help install bugs for the return flight.

Complaints were made about the wiretaps in Italy, as well.

Some of those charged in Calabria based in part on the recordings made in Canada appealed their conviction, but Italy’s high court accepted the operation was legal in Italy because the bugs were installed on the phones in Italy and the recordings captured on them in Canada were transmitted to Italy before they were listened to by police.

In Canada last year, in anticipation of this deportation hearing, DeMaria’s lawyers asked the IRB to exclude the wiretaps, along with other evidence, from the record of the case. They said the wiretaps would be considered illegal in Canada’s courts.

Dolin refused their motion in October, saying that under Canadian law, immigration hearings used different rules of evidence than criminal courts.

“When it comes to entering documentation as evidence, almost anything will be admissible as long as it is relevant to an issue to be decided by the IAD (Immigration Appeal Division),” Dolin wrote in that ruling.

The interruption to this hearing and complaints and arguments over evidence and process are not as surprising in a case against DeMaria as they might otherwise be.

Ottawa has been trying and failing to kick him out of the country for more than 40 years.

DeMaria has lived in Canada for almost all his 71 years after emigrating from Italy with his parents when he was nine months old, but he never became a Canadian citizen. The door to citizenship slammed shut after he was convicted of shooting a man who owed him money, killing him at a fruit store in Toronto in 1981.

Ever since his second-degree murder conviction, the government has been trying to deport him, with each attempt fully challenged and litigated by DeMaria and a battery of lawyers.

He was released from prison on full parole in 1992 and lived without legal problems for some time. Over the years, however, various police investigators alleged he grew to become an influential member of the ‘Ndrangheta in Toronto.

At one immigration hearing a police officer named him as the mob’s “top guy in Toronto.”

At a previous immigration hearing in 2023, DeMaria denied being a mobster, or knowing anything about the ’Ndrangheta, apart from what he had read in newspapers. He claimed ethnic profiling and anti-Italian prejudice was behind efforts to deport him.

Dolin gave lawyers for both sides at this hearing until the end of August to send him all of their arguments and responses in writing for him to rule on DeMaria’s stay motion.

The hearing was scheduled to reconvene in October unless he told the lawyers otherwise.

• Email: ahumphreys@postmedia.com | Twitter: AD_Humphreys

Our website is the place for the latest breaking news, exclusive scoops, longreads and provocative commentary. Please bookmark nationalpost.com and sign up for our daily newsletter, Posted, here.

Comments

Be the first to comment