Valley View Groc. and Conf., Gas Bar

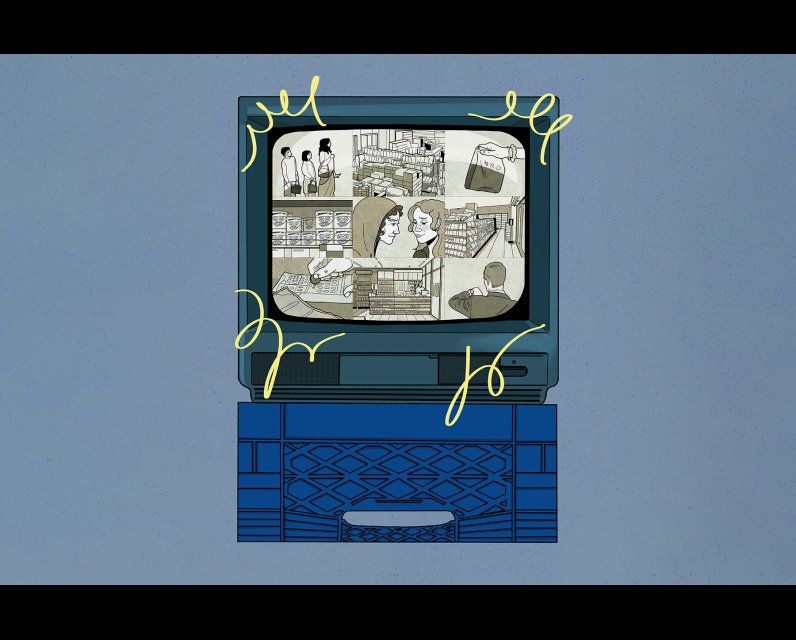

There’s surveillance video. The screen displaying nine squares, and in each square, a different aisle, a corner, the check-out counter, every part of the store visible. The aisles sometimes humming with emptiness, a soundless hum, the pixels building to a vibration of stillness that occasionally breaks up the image, like the sleek fur of an animal bothered by a fly. The image shivers. It can’t contain the stillness, lying in wait, a predator, in the soft grey palette of surveillance video. The nuanced delicate shift in a thousand different greys and whites and darkish greys, but mostly light greys, that camouflage the things on the shelves. Everything too bright, overlit, but grey as grey can be, except for the rims of tin cans, white hot, so shiny the lids of the cans make a pool of obliterating circles, so white the disks seem to burn through the surveillance tape.

The cans don’t move, the camera doesn’t move, the fluorescent lights don’t move, but the lids of tin cans on the top shelf in the third aisle, shown in the top left corner of one of the squares of surveillance video, are animate wobbling dapples of pure white light.

A figure in a black hoodie enters the frame, the pixels reconfigure, reconfigure. He stops right in front of the cans and is transfixed. The customer is stupefied by the choice between SpaghettiOs and ravioli. The head raises, it’s the boy.

The boy the girl behind the counter thinks is the most beautiful person she has ever seen. His eyes are raised toward the ceiling, he is calculating how much bologna he can get if he gets the SpaghettiOs and Coke instead of milk. He wants milk but it’s much more expensive. There’s the new tax on sugar drinks, but even with the sugar tax, Coke is cheaper. The milk is too much.

His girlfriend said they need milk, they need formula, they need a stroller, they need a car seat, they need Pampers. His face in the video is milk pale. Beatific. He glances toward the cash and puts a can of SpaghettiOs in the pouch of his hoodie. She sees him do it on the screen near the cash.

Stealing an ATV from a shed, takes his father’s drill, the boy, and unscrews the doors on the shed, two doors held together in the middle by a latch that’s padlocked, jimmies the doors to the side of the shed, removing them from the frame, rolls the ATV down the lane in the dark, an old one, easy to hot-wire, drives it into the bushes and returns to put the doors back on, fitting them back over the door frame, squatting, his pinky, searing pain, receding pain, tingling, the life jackets, the Ski-Doos, the Sea-Doos, the mountain bikes, the Black + Decker table saw, the chainsaw, an old sleigh, the red tool box, tools hung on a pegboard according to size, all of it belonging to a couple who work at the taxation centre in town, and she, the wife, with walking sticks and fleece and the kayaks, checking her steps on her app. Who are only there on weekends, maybe every second weekend, Tilley hats; the boy holds the doors of the shed back in place with one knee, one shoulder, and repositions the screw in the hole and fits the cordless screwdriver into the tip of the screw, and vroom, and another screw, vroom, takes the next screw from his teeth, vroom, so loud in the dark, the doors back in place.

Council hasn’t put a streetlight on this road, the last screw bites the wood, he trots down the lane, blood pounding in his temple, hot-wires the ATV in the light of his phone, goes up the railbed, rides through three communities, and at the crest of the cliff, stops. Bike idling.

Because it’s dawn now, had to stop because of the sun on the water, an infinity of dapples blaringly pink as they roll into shore, and the foam on the waves pink, and the amberness of everything, the trees, the boulders, whales, so many whales, slipping up, slipping under. He can smell the spray from their blowholes, the dew of the grass, the light spreading over the rippling grass, she wants milk, she wants a soother with water in it and a textured surface which you put in the freezer so the baby can teethe, the ice soothing, she has all the books from Value Village, from the Sally Ann, and the baby books say soother, they say breastfeed. But she can’t breastfeed, she says, that’s gross.

He goes to the counter.

Bologna, five bucks’ worth, he says. She flares up, the colour in her cheeks. Bites her bottom lip. All silly, she is. Takes the log of bologna from the fridge, the mah-wah when the rubber seal of the stand-up fridge door lets go, like a sloppy kiss, lays the bologna on the slicer, flicks the switch, the whir of the blade, positions a piece of wax paper, the smell of pressed meat, the faint, deathy, turning smell, the fridge smell, and the waxy rind, smell of the wax casing on her fingers and pink-grey animal.

How thick do you want it? she asks.

His eyes. They are big, and his hair is thick and longish all around his face in curls under the hood, and the door swings open, a man strides up to the counter, looking around with bullish swings of his head, like, how long will this take, like, I’m important, I’m in a suit, with his credit card turning end over end on the counter, making little snaps on the counter she can hear over the slicer, each slice tipping over onto the wax paper.

Then, Mrs. Turner who will hold up the line buying Scratch ’N’ Wins, and who insisted on putting up the blurred poster of her lost cat, her brooch with all the cut-glass gems, a peacock, the spray of jittering red and purple and orange dots of reflected light on her quivering throat from the peacock, as she ducks her head to trawl her purse, one gem missing, the teensy brass claws supposed to hold the jewel clenched around nothing, nothing, her false teeth too uniform, too white, as she pulls the tabs on the Break Opens and wins twenty bucks and buys more Break Opens and a Scratch ’N’ Win. Every day she buys a pack of smokes and holds them up, blazing with fresh astonishment at the price, she lifts them in the air and waves them slowly, turning to the lineup behind her, demanding the other customers join in her bafflement at the price.

Twenty bucks? Twenty bucks? she asks them if they can believe it, she says she can remember when they were five bucks, she touches her brooch as if that is the engine of her memory and stands there at the counter, arm raised and swaying, demanding their attention, lost in some time when everything was cheaper, before the adult diapers, before the tinnitus, before home care twice a week to do the meals in Tupperware with their crystalline fur of freezer burn, before her daughter moved to Alberta, before the cat got so skinny she could feel her spine, her ribs, slept all the time, inert, the fur matted but who could afford the vet, and then she disappeared from the garden.

Behind Mrs. Turner, the mother with the two youngsters, her bright orange sari under her raglan, the hard-edged briefcase, ruby lipstick, stylish eyeglasses, the children with metal lunchboxes, Disney characters, how the youngest tries to pick the Rice Krispies square with the pink sprinkles from all the squares under the counter, tapping the glass with his finger, insistent, No, not that one, the one behind, yes, that one! That one!

The girl tells the lineup she’ll just be a minute, she’ll be with them.

She has adjusted the dial that determines the width of the slice of bologna, she is perspiring because he is radiant, the boy, the young man is radiant, and because look what his proximity is doing to her. She can hardly stand to look up at this boy, a heat, so beautiful and solemn, about the bologna.

The lawyer at the counter picks up one of the egg sandwiches the girl made this morning, she made egg, tuna, chicken salad, cream cheese and jam, the plastic wrap drawn so tight the egg smears against it.

I’ll be with you in a second, she says to the man with the credit card, the lawyer with the egg sandwich, she sees the back of him in the surveillance video, the pants too long, the jacket so tight there are three wrinkles pulled taut between his shoulders, but the glare on the screen makes his legs winnow into two points, like toothpicks, his feet disappear into the floor.

She hears her father at the adding machine, in the little office crowded with cartons of cigarettes, toilet paper, his desk squashed in, he uses the machine that came with the store, instead of the calculator on his phone. She hears the squeak of her father’s office chair as he pushes back from the desk with his heels, pushes back from the adding machine, as if blown back by a great wind—they are getting a hurricane, the radio said—and the receipts and the awful truth of how will they meet the gas bill, they are being carried, her father says, carried, last week they were carried by Esso, Central Dairies, the smokes rep, her father shoves himself away from the desk, hands locked together at the back of his head, elbows out.

Mrs. Turner is asking the lineup if they know who the winner is yet? Anybody know? Has the winner been identified?

They’d sold the winner, the winner, they had the winner, the 16 million, they sold the ticket, four weeks ago, five weeks? Six? They got the phone call at the store, they were the vendor. Somebody bought the winning ticket from her or her father or her mother or Mrs. Mercer who only comes in for one shift a week so her parents can have Sunday afternoon together which they spend in bed.

But the winner still hadn’t come forward, and their share, her father’s share, for being the vendor, the guy who sold the ticket, his store, he gets a percentage of the overall winnings, and that could cover the gas bill, but the winner has a year before they step forward, somebody in the lineup said, the winner is getting their ducks in a row, the winner has to think what they’ll do, be prepared, because they’ll come out of the woodwork, the relatives of the winner, or charities, everybody will want a piece of the winner; or the winner doesn’t know, the winner lost the ticket, the winner is oblivious to their good fortune, has yet to discover they are a winner, and so after school, she has been going over the surveillance video, when she doesn’t have cheerleading or figure skating, all the customers, fast-forwarding them through their gestures, their contemplations and purchases, the light of the video going dark, going bright, as the hours pass in minutes, seconds, people speeding in, speeding out of the store, waggling and jerking like wind-up toys, like robots malfunctioning, at the counter in greys and whites that go dark and lighten up, jostling each other, their gaits automated and harried, little jerky nods of their heads as they chat, she has watched maybe nine hours, so far, maybe twelve, fast slow fast slow fast slow, what they put on the counter, most of them regulars. She is watching for whoever is behind the counter turning to the machine that spits out the tickets, she is watching as she or her mother, or her father, or Mrs. Mercer, sells the tickets, sells everything. Waiting for the winner. Stop. Start. Stop. Start.

She is watching for the boy too. She puts the boy in slow motion. Studies what he buys, how he slowly moves a curl of hair out of his eyes. For a few days, maybe a week, he had the trace of a moustache, then the day it was gone, the day he came in soaked to the bone.

But now it’s the morning rush, and they are piling in, because of the hurricane, weather warning in effect, because of the drop in gas prices, rushing to fill their tanks, every other customer asking if the winner has come forward, not forward yet?

The lawyer looking at his watch, shaking the cuff back from his Fitbit, four youth in custody, and if the traffic isn’t bad he’ll get to the RCMP detachment before court, and whoever’s the Crown today, because if it’s John, John never met a kid he thought shouldn’t be in jail, John with his Lycra shorts and broad chest of lime-green Lycra, his chest flung out, fists pumping, running around the lake, John sending kids to Whitbourne like each incarceration is a personal win, but Gillian, he could get Gillian, she might be the Crown if he’s lucky, she doesn’t fuck around, Gillian, she makes a decision. All this lawyer has to do, his credit card tapping the counter, is look at a kid to know he’s innocent, the lawyer knows these kids, he can smell guilt, practically, and the little fella drunk driving, maybe seventeen, two more in the car with him, hit a pole, could have been killed, depends on the judge, or if the lawyer is late, the judge might be pissed, the lawyer will ask for youth diversion for the drunk driver, maybe the kid writes an essay, picks up garbage, the girl behind the counter taking her dead time, last thing he needs, to be late. What the hell is that girl doing?

The girl behind the counter can barely raise her eyes to meet the boy’s eyes, this boy lifting his chin, a little jut of his chin, letting her know to keep cutting more bologna, to keep going, slice after slice, flopping one slice on top of the other on the wax paper, and it’s a serious load of bologna.

The ATV covered by alders, he drove it through the alders where there’s a little clearing, and slapped some paint, scratched off the serial number, got it on Facebook, and now he’ll get the goddam car seat or bouncy chair, the Pampers, put the doors back on the shed so he could buy himself a week, maybe two weeks if they don’t come out for a little trip in the kayak, the Sea-Doos, the couple from the taxation centre, if they don’t know the ATV is gone, if they don’t look in the shed, he’ll have it sold inside a week, less than a week.

Keep going, he says, another jut of his chin, bologna, eggs, she made him be there, his girlfriend, when the baby was born, she made him be there. This is now, he has a kid and dropped out, and the old truck he bought for fifty bucks, for parts, up on blocks, and the fish plant night shift, see if he can get his stamps, he’s got chickens and the egg yolks are orange, not yellow, orange, but the rat in the chicken coop and she set up a camera, the girlfriend, and called him when it came over her phone, the live video, the rat in the hen house.

He’s in there now, she said. It moved into the light, a bare light bulb for heat, sitting back on its haunches and smoothing its whiskers, like he’s in a soap opera, the rat, and she phoned him, because he was out in the garage, and he got the BB gun and shot the little bastard. That was a moment, her on the phone screaming, the rat exploding. He has the weed growing, which he will sell, a room of tinfoil with the lights and stink, the greenery and the vivid funk of it. And she selling buckets of blueberries she picked, on the hood of his car out on the highway.

That’s enough, he tells the girl behind the counter. The baby, his baby, the bong on the coffee table, the blood of the placenta, he’d never been in a hospital before, except when he was born himself, all the people who took over, the nurses or whatever, the way they talked to each other as if it were all ordinary, and they told her to Come on, come on now, that she could do it, and he got in their way, they said, Excuse me, but they got excited toward the end of it, even though they’d seen it all before, they were patting him on the shoulders, they clapped, they all clapped, how she twisted, and the noise coming out of her, and when it was over, the baby girl wrapped up, the polite awed clapping, she sent him down to Tim’s for a sandwich and he got lost, wandering through some other wing where there were people in wheelchairs, some who had lost a limb, old men whose faces were like the ash, the delicate, caving ash from a long-burning cigarette, fragile wrinkled faces, so grey and craggy, the johnny coats, he’d seen the wink of a white flabby arse, an old man’s arse, another man standing straight, strong arms, with one leg and crutches, and on the white bandage over the stump, a growing spot of very, very bright blood. Tears sprang to the boy’s eyes out of nowhere, because this was the wrong ward and he’d walked and walked forever, for the girlfriend. She’d sent him on a quest. Coffee and a muffin.

He didn’t know if he could take her, she was a loud mouth, she said mean things, he hardly knew her, but there she was on the couch watching TV after picking berries, the baby in a sling, she told him she had to have a sling, and she had been right, she cleaned all day with the baby in the sling, and cooked good stuff, but she bossed him around, the mouth on her, and look at this girl behind the counter, so pretty, beautiful, and all mixed up, shy, muddled, taken with him, and they couldn’t help looking at each other, the baby squawking, and his girlfriend weeping or raging and wanting all these things, the milk, she craved milk, first she used a glass like a normal person, but then straight from the carton and glug, glug, glug, and she put the carton down, wiped her face with the back of her hand and her eyes glittering, he really knew absolutely nothing about her. He was only seventeen, he had come to understand that, became aware that he was young and he had never known that before, too young, the social worker said.

The shock of the old man’s naked body underneath the johnny coat, because they didn’t pack a bag or anything, he and the girlfriend, so he had to go get her something to eat at Tim’s, and he was lost, lost, but the whales and the smell of them, the honking spray, he tried to count maybe there were fifty whales, maybe sixty, the amber light stealing over the boulders and the long grass. His thighs trembling because he’d just fucking stole an ATV and got away with it.

The girl puts the pile of bologna on the scales and the red digits flutter madly, up down up down up down, it is under ten bucks, which he can handle, he reaches over the counter and takes a slice off the top, peels the waxy rim and drops it into the trash on top of a pile of ripped Break Opens with lemons and cherries and bells, and he folds the piece of bologna and eats a third of it, so the end hangs out of his mouth, like the pink tongue of a panting dog, just for a second, before he takes another bite.

The lawyer yanks at the cuff of his shirt, making it stick out half an inch from the jacket sleeve, four more people behind him now, and the pumps full. Would the hurricane start when he was on the highway, or after court, dead still outside, dead still. Not a breath.

The boy in the hoodie steps in front of the lawyer, in front of everyone, she’s put the bologna wrapped in brown paper with the price in marker, the marker squeaks as she writes, the smell of the marker making her nose crinkle, waking her up, $8.72, and she draws a happy face, next to the price, and she carries the package of meat to the cash, and rings it in and rings in the milk.

It is so hard to look up when she asks him, but she absolutely has to ask him, her eyes so heavy, she had taken a lot of time putting on the mascara, the hard bristles on that little brush, almost lifting her eyelid from her eyeball, the tug of that brush, into his eyes, palest blue, the dark lashes, freckles across the cheeks, plump lower lip, but she does, she forces herself to look, she makes him look at her too, she is aware of the quality of attention she’s giving him, she knows him, she has eaten him up, they are each other, this is new, a kind of crush that wipes her out, she is fifteen, her heart is so loud in her ears and her cheeks hot, and what does she know about him? Nothing about him, except the folded bologna, the hunger, the hurricane that’s supposed to come later in the afternoon, upgraded, a woman says, she is reading from her phone, category six, the heat from this boy, what the romance novels she reads call aroused, she has imagined his mouth on her mouth, and the weight of it, the throb of just that much, just that little bit, just a kiss, the tip of his tongue, while she’s in bed, drifting to sleep, and she had maybe her first really hard intense orgasm, is that what it was? Without even moving, and the thrill of it, the newness.

And the SpaghettiOs? she asks.

He looks up from his phone, there has been a ding, somebody already wants the ATV, it will be gone by five, he unwedges the can of SpaghettiOs out of his hoodie pouch and puts the can on the counter. The lawyer clocks it. The sign, Shoplifters will be Prosecuted, over the ice cream cooler. She called him out, she fucking ratted him out, the boy can’t believe it.

She rings in the SpaghettiOs.

He hands her the money and she can’t count back the change. She is paralyzed. People leaning in now, people in the lineup, to see what’s making this so slow, she has named him for the thief he is, it’s her father’s store, and he has to pay, she is always watching the video surveillance, she knows, her palm out with the loose change and the bills, but she can’t count it back, and he so fucking angry that she mentioned the SpaghettiOs, made him pay for the SpaghettiOs, she has no idea the tremendous pressure he’s under all the fucking time, he was raised by a single mother, has five siblings, two in foster care, and the puppies near the woodstove, pink as can be, red-rimmed eyes closed, and how one died and how he raised the others and sold them, one by one, over Facebook, and loved them as he will never love anything, anything, but now an infant he has to take care of, fuck her SpaghettiOs, and he will not help her, he will not reach into her hand, turned upward, cupping the change, his money, ready to give it back to him but unable to count it.

The lawyer rips the plastic wrap off the egg sandwich, and the court stenographer will begin typing, and wolfs it down, half the sandwich in two bites, and it is so good, just the right amount of mayo, salt, he’ll get these four kids off, because 99 percent of the time all they need is a good scare, bang, they hit a parked car loaded drunk, and a fire hydrant, bang, a good scare, having to face a judge in a court of law, all the pomp, the theatre, remove your hats before the judge arrives, everybody, remove your hats, give a testimony maybe, and they’ll never do it again. They’ll never get behind a wheel intoxicated again after that.

Okay, okay, the boy reaches into her palm, but he does it so slowly, he makes a holy show of her, everybody can see she can’t count because she has this stupid crush, taking the quarters first, snapping them down on the counter, counting as he does it, oh the condescending tone as he counts out the change, he is touching her, and she can’t hear anything but his voice because everyone can see she’s blushing, she is blushing so hard she can’t count the change back.

Then he remembers the Pampers.

He says, Wait! and he knocks into everybody getting to the back of the store and knocks into them again getting back to the front of the line, actually knocking the lawyer to the side with his shoulder, and puts down the Pampers on the counter.

The rain splats the windows, strong, as if someone had thrown a bucket of water, and the whole store is rattling because the wind has picked up, the sign over the outside of the door creaking, slapping back and forth, there was no rain, no wind, there are lashings of torrential rain, 150k winds, just like that, like wrath, like an opera, or the way she leaps into the air and twirls, arms over her head, elbows bent, making a diamond with her arms, the whole rink a spinning blur, and down, the skate blades hit the ice, shaving it up, glides one leg out straight behind. She will blur him away, get rid of him. Never think of him again.

She looks at the package of Pampers and says, Six to eight weeks?

She stammers it out again: Six to eight weeks?

He’s not mad about the SpaghettiOs now. He has betrayed her, he knows it. He has betrayed her, he has betrayed those puppies he sold, he has betrayed the girlfriend and her buckets of blueberries on the hood of his beat-up Toyota Corolla with the manifold gone, no manifold so the roar of car wherever he goes, a big racket, and the radio always off the station, he has betrayed his infant daughter, by regretting her, just for a millisecond, regret, but then such an overwhelming love, her little fingernails, the way her eyes flick under their lids when she’s asleep. Regretting he is young and regretting dropping out of high school and regretting the crab boat and the welts all over his body where they pinched him, for three months of the summer, the acid or whatever the fuck they leak stinging so bad, and the weather, and the hours and the chicken whose head he chopped off with the axe and how long it lasted after that, the chicken, the girlfriend and her milk moustache and her grin, regretting all the milk, the cost of it.

Because he’d had this girl’s attention, the girl behind the counter, he had allowed it, felt it, in the store bright as diamond is the truth of it: he has a baby, and his life is all blazing light and not stopping for anything.

The store is a diamond or a fossil, that is the imprint of her adolescence. The brightest thing was the slicer. The brushed steel, a very soft grey. Her father keeps it clean. The bologna with the faint colours in the waxy skin, a pale red, a soft blue, like the advertising for beer in the milky ice of the skating rink, when she grabs the blade of her skate from behind and spins, her chest out, her ponytail. The whir of the slicer blade was muted. It was a whisper.

How she had set the dial to a thickness, a very particular thickness, and asked him: And the SpaghettiOs?

He said, Make it thicker. Other customers with big families ask her to make it thin, so there’d be enough for everybody at the table. The sheaf of bologna curling away from the blade, and another, and another.

The thunder over the store, right over the store, over their heads, so loud, a net of lightning, smacking down on the lot, on the store, on the trees in the distance, everywhere, lightning.

Then the power failure.

Lost the electricity, the lawyer says.

The whole city, it looks like, says someone by the window.

The whole island, someone on their phone says.

Everything shut down, someone else on their phone.

Her father emerging from his office, bewildered, broken.

The sudden, artificial gloaming. The dusky rustle of someone’s rain jacket. The gonging sign outside banging so hard against the store.

The fridges, the cash register, the surveillance cameras, the lights over the gas tanks on the lot, going out, out, the silence, as if they were in church or somewhere actually holy. They were holy together. She shut her eyes and saw his upturned face, the eyes, in the surveillance video, what? Five, six weeks ago? Fast forward, slow motion, too young, younger, older, too old.

Her hand and his hand in the surveillance video, she remembered it now, she’d passed him a lottery ticket. He’d bought a lottery ticket.

Normal speed, he lifted his eyes.

The post Valley View Groc. and Conf., Gas Bar first appeared on The Walrus.

Comments

Be the first to comment