The Artist Who Tries to Paint Trump’s Soul

.main_housing p > a { text-decoration: underline !important; }

.th-hero-container.hm-post-style-6 { display: none !important; }

.text-block-underneath { color: #333; text-align: center; left: 0; right: 0; max-width: 874.75px; display: block; margin: 0 auto; } .text-block-underneath h4{ font-family: "GT Sectra"; font-size: 3rem; line-height: 3.5rem; } .text-block-underneath h2{ font-size: 0.88rem; font-weight: 900; font-family: "Source Sans Pro"; } .text-block-underneath p { text-transform: uppercase; } .text-block-underneath h3{ font-family: "Source Sans Pro"!important; font-size: 1.1875rem; font-weight: 100!important; }

.flourish-embed { width: 100%; max-width: 1292.16ppx; }

.th-content-centered .hm-header-content, #primary.content-area { width: auto; } .entry-content p, ul.related, .widget_sexy_author_bio_widget, .widget_text.widget_custom_html.widget-shortcode.area-arbitrary { margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; } .hitmag-full-width.th-no-sidebar #custom_html-45.widget { margin: auto; } @media only screen and (max-width: 768px) { .img-two-across-column{ flex-direction: column; } .img-two-across-imgs{ width: auto !important; max-width: 100%!important; padding:0px!important; } .main_housing, .text-block-underneath { margin-left: 25px !important; margin-right: 25px !important; } .text-block-underneath h4{ font-family: "GT Sectra"; font-size: 35.2px; line-height: 38.7167px; } } @media only screen and (min-width: 2100px) { .main_housing, .text-block-underneath { margin-left: 32% !important; margin-right: 32% !important; } } @media only screen and (max-width: 1200px) { .main_housing, .text-block-underneath { /* margin-left: 25px !important; margin-right: 25px !important; */ } } @media only screen and (max-width: 675px) { .main_housing, .text-block-underneath { margin-left: 10% !important; margin-right: 10% !important; } } .hero-tall {display: none;} .hero-wide { display: block; } @media (max-width:700px) { .hero-wide { display: none; } .hero-tall { display: block; } } ARTS & CULTURE / DECEMBER 2025 The Artist Who Tries to Paint Trump’s Soul Can art reveal the true nature of the American president? BY RICHARD WARNICA ART BY ISABELLE BROURMAN

Published 6:30, October 1, 2025

How do you picture Donald Trump? When you close your eyes and summon his name, what do you see? Is it the fake tan—orange and blended so badly it shears off like a shoreline at low tide along his ears? Maybe it’s the hair—that improbable swoop. Or the scowl and squint. Likely it’s some combination, all the broad and laboured tics of a man permanently performing a kind of political drag.

Two days before Trump’s second inauguration, this past January, I was in the Phillips Collection, America’s first museum of modern art, in Washington, DC. I was walking through the galleries with Isabelle Brourman, the artist who has come closer than any other in my mind to excavating what there is of Trump’s soul.

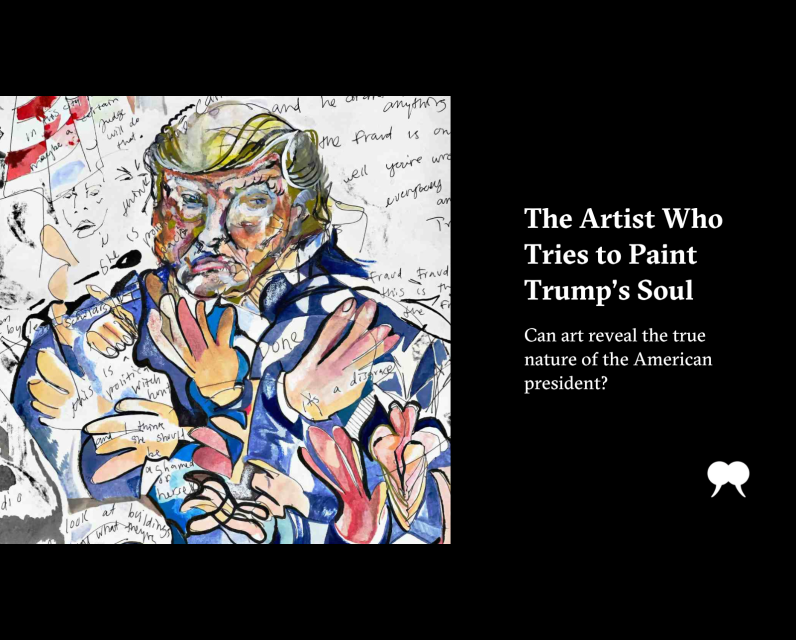

I first met Brourman in court in New York, at Trump’s trial for criminal fraud, which Brourman was sketching and painting daily for New York magazine. I had been writing about Trump for more than eight years by that point. I was used to the effect he has on a room. He says and does so much. It often feels impossible, in the moment, to adhere to any one thing. To my mind, no one has ever captured that kaleidoscopic inconstancy the way Brourman has. Her works are kinetic. Her trial paintings, several of which were recently exhibited at a solo show at the Will Shott Gallery in Manhattan, collide images and words. Witnesses, testimony, symbols, unearthly colours and improbable faces: they all refract and react on the paper.

Brourman and I were both in Washington for the inauguration. We had agreed to meet up one morning to look at paintings at the Phillips, an old mansion near Dupont Circle. As we walked through the galleries, she pointed out works that caught her eye. When we entered one room, she gasped in front of a large canvas by Joan Mitchell, one of the great abstract expressionists of the mid-century. Later, she spent several minutes studying a pair of lithographs by Honoré Daumier, a nineteenth-century French artist, satirist, and sculptor known, among other things, for his courtroom sketches from the Palais de Justice in Paris.

Brourman was scheduled to paint Trump at one of his inaugural balls. She had come to the museum directly from an event space where she had set up her easel next to a spot reserved for Doug Mills. A New York Times photographer, Mills captured perhaps the most famous photo ever taken of Trump. A painting based on that photo—shot from below, moments after a gunman’s bullet nicked Trump in the ear last summer—now hangs in the White House, replacing a portrait of Barack Obama.

When we sat down, Brourman told me about travelling to Mar-a-Lago last summer to paint Trump’s portrait just weeks after the failed assassination. In the final work that came out of those sessions, Trump looks almost beatific. His wounded right ear is literally glowing. Were it not for one element, you’d almost call the work flattering. But there’s a tell in the eyes. Looking out from under Trump’s blonde eyebrows are two black ovals. The colour is so dark it’s less a shade than an absence—like deep space.

Brourman’s best works are an affirmation that, yes, everything is happening all at once, but also an assertion that all of it matters, every detail. You can’t edit it down. You can’t smooth the edges. You can’t look away. And if you stare long enough, you might finally get a feeling for what, if anything, is underneath.

In the Phillips, Brourman told me she explained the absence to Trump by quoting Amedeo Modigliani. The Italian painter is said to have once told a model, “When I know your soul, I will paint your eyes.” The quote appears to be apocryphal, but the supposed meaning, for Modigliani’s work, is clear enough: he left the eyes blank unless he knew the subject’s soul.

With Trump, I think it’s a little different. This is my interpretation, not Brourman’s. But when I look at the flat, black eyes in her painting, I see someone with no inner life at all.

I have long been fascinated by the juxtaposition between Trump and fine art. Before his first inauguration, I spent an afternoon at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, looking at the museum’s famous collection of enormous colour-block paintings by Mark Rothko. On the campaign trail last year, I jogged from Trump rallies to art museums all over the United States. I saw Helen Frankenthaler in New Jersey, José Clemente Orozco’s murals in New Hampshire, Cy Twombly’s ten-part Fifty Days at Iliam in Pennsylvania.

On July 13, 2024, Trump survived that assassination attempt in Butler, Pennsylvania. Two days later, I—along with several thousand other journalists—joined Trump in Milwaukee, at the Republican National Convention. It was there that I encountered the most effective and, to my mind, tellingly political work I would see all year.

I’m not a huge fan of most overtly political art. In my general experience, art that strives to be “important” first often ends up being “boring” second and third. This is not, to be clear, an invective for painters to stick to paint. I applaud anyone with a platform who uses it to fight for a better and more just world. Taken on the whole, I think the poets and artists of the world have been far braver and more outspoken about Israel’s campaign of slaughter and starvation in Gaza, for example, than have their colleagues in journalism or politics. I just think art and activism are different practices, with different methods and goals. Anyone who wants to succeed at either needs to know the difference between the two.

Rashid Johnson’s Untitled Anxious Audience (2017) is an exception to that admittedly pretty porous rule. The sculpture—a large rectangular grid of thirty-four horrified faces carved from soap and wax on ceramic tile—went on display for the first time at the Milwaukee Art Museum about six months into Trump’s first term. I don’t know if Johnson was directly inspired by Trump’s rise. But I suspect the work, with its panicked, swirling eyes and flat rictus grins, was at least informed by the world that created and enabled him.

Looking at the work that day in Milwaukee, the morning before Trump accepted his third Republican nomination for president, I felt like I had in Brourman’s studio that spring. It was like an emotional echo: an assurance, through the art, that someone else was feeling what I was too, that we are living together through a landslide of the uncanny and the inhumane and none of us are really holding on.

My personal interests in Trump and art have largely been rooted in a series of contrasts and connections. On one level, the art is just a nice tonic. Looking at one of Frankenthaler’s gauzy colour swirls after a Trump rally is like taking benzodiazepine for a society-wide panic attack. It just slows everything down. On a broader level, good art is true and beautiful. Trump’s entire political project is anything but. The deep contrast, I believe, is good for my writing and for my soul.

In my own work, I’ve mostly used the parallels and oppositions of Trump and fine art as rhetorical or literary devices. In the first eight months of the second Trump term, however, those links have become more literal.

As part of a broader cultural and fiscal gutting of the American project, Trump has sought to slash federal arts grants and replace the leaders of major public and quasi-public arts organizations at an unprecedented rate. In February, Trump had himself named chairman of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts (and was later officially elected to the position). Months later, Republican lawmakers introduced a measure to rename the centre’s opera house after his wife, Melania Trump. Not to be outdone, a different Republican put forward a bill in July to rename the entire centre after Trump himself. Both measures are still subject to full votes in the House and Senate. But when I was in Washington in June, separate portraits of the Trumps were already up at the Kennedy Center, beside the main stage door.

In April, officials from Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency met with the director of the National Gallery of Art, according to Bloomberg. The same institute eliminated its own office of “belonging and including” in January, following a presidential decree, according to the New York Times. In May, Trump announced he was firing the head of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. The president doesn’t actually have the authority to do that. But weeks later, the gallery’s director, Kim Sajet, quit of her own accord. (In September, Sajet was named the new director of the Milwaukee Art Museum, the same gallery where I’d first seen Rashid Johnson’s work the previous year.) In August, as a direct result of Trump’s cuts, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which funds, among other organizations, PBS, announced it was shutting down.

Several commentators have seen echoes, in Trump’s war on culture, of Nazi Germany’s fascist campaign against “degenerate art.” It’s easy enough to see why. “NO MORE DRAG SHOWS, OR OTHER ANTI-AMERICAN PROPAGANDA—ONLY THE BEST!” Trump announced in a post about the Kennedy Center in February, employing, like only he can, the diction of a toddler and the spirit of Joseph Goebbels. Those echoes have certainly become louder after the assassination, in September, of the right-wing activist Charlie Kirk.

At the same time, I’ve never quite felt like fascism was the right lens through which to view Trump’s personal or cultural projects. He has empowered fascists, certainly, and the broader movement he created has been teetering more and more in that direction. But Trump’s own aesthetic tastes aren’t fascist. “Fascist aesthetics is based on the containment of vital forces; movements are confined,” Susan Sontag wrote in 1974, “held tight, held in.” Trump has never held anything in his life. His tastes bend toward excess and gold. One writer recently called his Oval Office redecorations a “gilded Rococo nightmare.” The unifying theme of a recent exhibit on the Nazi war on degenerate art was “hate,” Patt Morrison wrote in the Los Angeles Times. The unifying theme of everything Trump does is “more.”

This isn’t to diminish the dangers Trump poses, to American democracy, to vulnerable people, to the world. It’s just an argument that fascism, culturally, isn’t what he, personally, is doing. I have no idea if Trump actually believes half the things he says. But I am pretty sure he doesn’t care one way or the other.

Trump doesn’t have a central intellectual or cultural project. He just wants more (literal) gold. I’ll give you an example. When I first covered him, in 2016, I was horrified by the way he spoke about Islam and Muslims, and even more horrified by the way his crowds reacted every time he said things like “I think Islam hates us” or told a debunked story about a US general killing Muslims with bullets dipped in pigs’ blood. When I returned to the campaign trail last year, I was confused at first, then terrified, to find that trans people had replaced Muslims as his go-to punching bag. At multiple events over more than twelve months, I saw Trump whip up his crowds by vowing to get “transgender insanity the hell out of our schools” and to keep “men” out of women’s sports.

Trump didn’t invent American Islamophobia or demonization of trans people. That’s not what he does. Instead, in both cases, he heard it. He echoed it. He found it effective, so he amplified it, no matter who it hurt, how many people it got killed.

That’s what I mean when I say he has no central project. It’s what I see when I look in the blank eyes of Brourman’s Mar-a-Lago portrait: a man with no core beliefs who will say and do anything to advance himself. The self, after all, is the tenet to which Trump truly ascribes. In that way, he is less Hitler than he is the American answer to dictators like former Romanian leader Nicolae Ceaușescu or former Philippines president Ferdinand Marcos. Trump is a kleptocrat. He is looting America to get himself paid.

Brourman once referred, in one of our conversations, to the “glitteriness and the clarity and the details and crowdedness” of any live scene where Trump appears. I can’t imagine a better description of her own work. It’s glittery and clear, detailed and crowded. It’s messy, complicated, and true. That’s the way it usually is with good art. It’s rarely simple or direct; it hits at all the core things that are difficult to put into words. That’s also why, with exceptions, good art and good activism are so often such different projects. Effective activism is insistent, straightforward, collective, and unrelenting. The goal isn’t creation; it is change. Art is a different endeavour, with different ends. It’s an alchemical mixture of documenting what is while also creating something new.

That isn’t to say the two can never intersect. Recently, Brourman has been back in court, painting asylum hearings in New York. In July, a photographer captured her in a courthouse hallway, sketch board propped against her hip, pencil in her right hand. In the photo, a masked Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent is staring down at Brourman’s paper. He’s looking at a picture of himself. “Documenting the surreal discrepancy between court proceedings—judges’ orders—and the subsequent detainment of respondents by ICE agents in the hallway,” Brourman wrote under the image on Instagram. “Clashing protocols abound.”

The post The Artist Who Tries to Paint Trump’s Soul first appeared on The Walrus.

Comments

Be the first to comment