How Jane Goodall’s Breakthrough Began with a Chimpanzee in Tanzania

My partner Travis and I were speed-walking along Toronto’s Front Street on our way to Meridian Hall. We had rushed straight from work, fought the inevitable traffic along Highway 401 between our home in Guelph and Toronto, and grabbed a quick bowl of lobster bisque from St. Lawrence Market.

As we neared the theatre, we could see crowds flocking toward the entrance. Puffing a little from our swift walk, we showed our tickets to the usher and made our way to our seats.

“This way,” I said.

“Really?” Travis asked as we walked closer and closer to the front of the theatre.

I grinned and nodded. I had sprung for the good seats.

We finally stopped, just five rows from the stage. I pulled off my coat and turned to hang it on the back of my seat. As I did, I paused to take in the 3,000-seat theatre that was rapidly filling up with people of all ages. A woman behind us wore a traditional African dress. Another woman had brought her golden retriever service dog with her. The two men beside us, dressed in suits, looked like Bay Street traders. I scanned the audience to see if there were any familiar faces.

“I don’t see anyone we know,” I said. Primatology is a small world, and it wouldn’t be surprising to spot a few colleagues. I turned back around and looked at the stage, where a couch and a podium were ready for the honoured speaker. Several stuffed animals were lined up neatly on the podium.

My heart pounded in anticipation. The Jane Goodall would soon take the stage. This was a woman who, driven by her fascination with animals, had travelled across the world to complete the first long-term study of wild chimpanzees in Africa. She made huge discoveries that contributed to our understanding of primates and human evolution. This was one of Goodall’s first live events since the pandemic, in late 2023, and would showcase her groundbreaking research on chimpanzees and her focus on primate conservation and climate change.

As we waited for the lecture to begin, the theatre buzzing with excitement, that burning question popped into my head: Why have so many women been drawn to the discipline of primatology? In that moment, one answer seemed obvious: Goodall was a role model to everyone in that theatre and to the many women who would go on to study wild primates, myself included.

I elbowed Travis. “Do you think she’ll talk about the termites?”

Those small insects with their wriggling winged bodies and large red heads turned everything upside down.

The year was 1960, and Jane Goodall, a twenty-six-year-old Englishwoman, had travelled to the mountainous Gombe Stream National Park in western Tanzania. Gombe is nestled on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, the second largest lake in the world by volume. British explorers in 1860 described it as “an expanse of the lightest and softest blue” and “sprinkled by the crisp east wind with tiny crescents of snowy foam.”

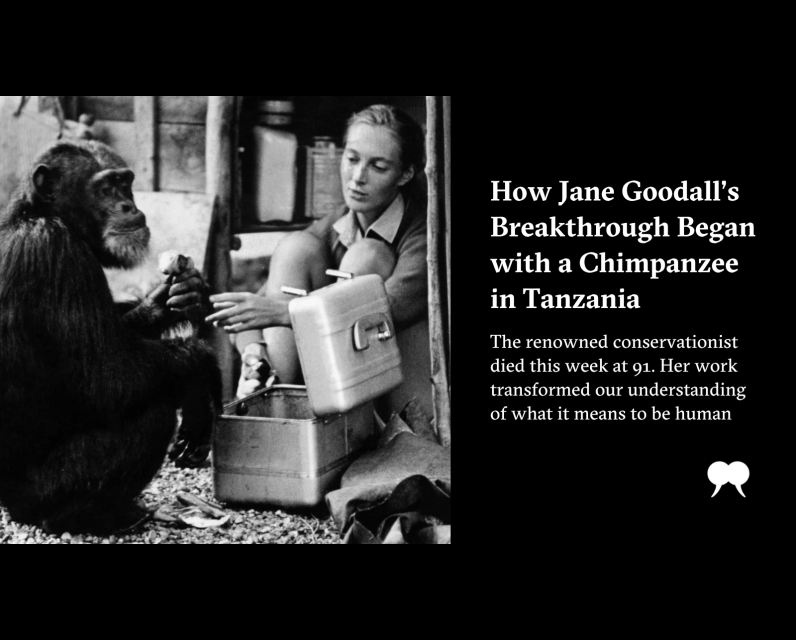

On the shores of Lake Tanganyika, with high mountains as the backdrop, this deceptively demure-looking young woman, with her characteristic low blonde ponytail, was filled with grit, determination, and a passion for wildlife. She was dedicated to studying and protecting wild chimpanzees.

That morning, Goodall had been up for hours, climbing up and down the valley, crawling on her hands and knees through dense undergrowth in search of the chimpanzees. So far, nothing.

It was October and the rains had come. Her khaki field uniform—shorts and a button-up shirt—was soaked from pushing through the wet foliage. This was not the first time Goodall had come up empty in search of the chimpanzees. These primates had proven elusive. Sometimes she would hike for hours without spotting a single chimpanzee, or, if she did get lucky, they would see her, call out in alarm, and flee. As a result, many of her observations were from a great distance: she would squat atop a perch on an open, rocky mountain about a thousand feet above the lake—“the Peak,” as she called it.

The chimpanzees, she would later write, did not at first accept this “strange white ape who had invaded their forest world.”

On that day, something caught her eye. A flash of black in the long grass about fifty metres away. Then, as though in a dream, the dark shape slowly came into view.

A black head. A long arm covered in jet-black hair.

She could see him fully now, his dark face with just a wisp of silvery hairs on the chin.

David Greybeard. Goodall had named this chimpanzee after David and Goliath, and Greybeard because of his silver chin hairs. David had been less afraid of Goodall than the others, and his presence calmed the group. Whenever Goodall spotted David, she knew she had a shot at getting up close with the chimps.

“In those early days,” she later wrote in In the Shadow of Man, “I spent many days alone with David. Hour after hour I followed him through the forests, sitting and watching him while he fed or rested, struggling to keep up when he moved through a tangle of vines. Sometimes, I am sure, he waited for me.”

Now, David was sitting next to a large mound of red earth on the ground—a termite nest—but what was he doing?

Goodall pushed a stray hair back behind her ear, quietly moved closer, and raised her binoculars to her face. She stood and watched, barely breathing, as David carefully poked a long stem of grass into the nest. The termites coated the stem. The chimpanzee raised it to his mouth and hungrily slurped up the insects with his lips, chewing each mouthful slowly and deliberately.

Goodall watched and waited, enraptured, as David fished for termites for an hour. She carefully observed and recorded everything she saw, and when he finally moved away, she rushed to the scene, where she examined one of David’s discarded tools and tried her hand at termite fishing.

In the coming days, Goodall would observe this behaviour several more times and with several other individuals. On a few exciting occasions, she watched as the chimpanzees prepared the twigs for use. If a leafy twig was selected, the chimpanzee would strip the leaves off. If the twig became bent in the process of fishing, the chimpanzee would break off the bent pieces. The chimpanzees were modifying the twigs in advance and with purpose.

Goodall knew that modifying a natural object for a particular purpose is the very definition of tool use. Before her discovery, scientists had regarded the ability to make and use tools as unique to the human species—a behaviour and cognitive ability that set us apart from the other primates.

Goodall sent telegrams—the text messages of the 1960s—to her mentor, Louis Leakey, sharing her observations. Leakey received Goodall’s communications with wild enthusiasm. He cabled a message back to the young primatologist immediately: “Now we must redefine ‘tool,’ redefine ‘man,’ or accept chimpanzees as humans.”

As a woman and a trained primatologist, I find myself reflecting deeply on Goodall’s extraordinary life and legacy. She was my first inspiration. She showed me that it was not only possible but necessary to travel to remote places, study wild primates in their natural environments, and advocate fiercely for their protection.

Goodall carved out an entirely new path in a field once dominated by men, redefining what it meant to be a scientist, a conservationist, and a woman in science. Her groundbreaking discovery of tool use in chimpanzees transformed our understanding of what it means to be human.

But her influence didn’t stop there. From pioneering community-centred conservation to founding the global Roots & Shoots program that continues to empower millions of young people, Goodall’s impact has been both profound and enduring.

On her passing, I feel immense gratitude—not only for her scientific contributions but for the personal inspiration she gave me and countless other women to believe in our voice, our vision, and our ability to make change. Goodall was, and remains, a force of nature. Her legacy lives on in every one of us she inspired to follow in her footsteps and to forge our own paths.

Adapted and excerpted, with permission, from Sisters of the Jungle: The Trailblazing Women Who Shaped the Study of Wild Primates by Keriann McGoogan, published by Douglas & McIntyre, 2025. All rights reserved.

The post How Jane Goodall’s Breakthrough Began with a Chimpanzee in Tanzania first appeared on The Walrus.

Comments

Be the first to comment