Stay informed

The woke pack comes for a Canadian hero

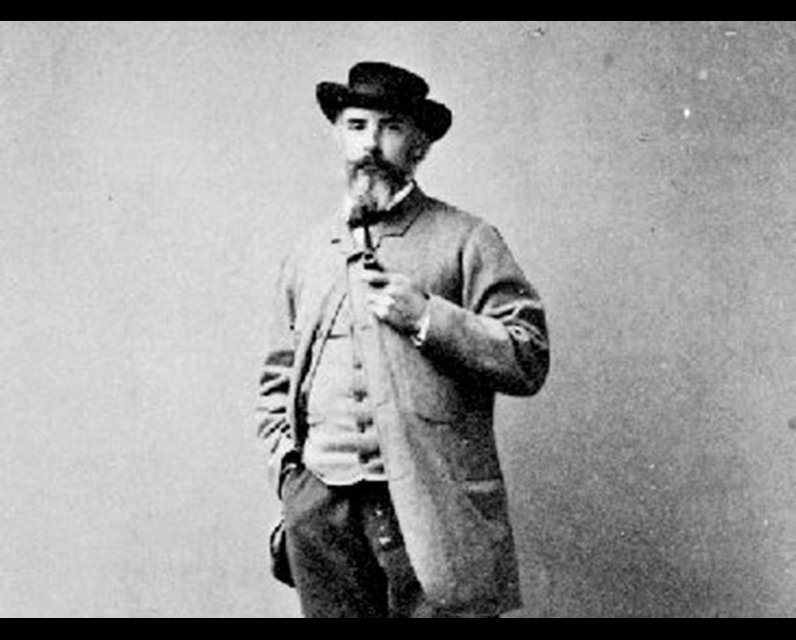

If he was American there would be a movie because Matthew Begbie had hero written all over him. He stood six-five, and when on a horse with his handlebar moustache and van dyke, he looked even bigger. Cutting a commanding figure, he tamed the Old West.

A circuit judge who brought bandits and outlaws to justice, he travelled the highways, biways and rivers of British Columbia before it joined Confederation. He went on horse, on foot, or by canoe, carriage or steamship, and carried out the law in a log cabin, under an oak tree, or in the open wilderness.

Begbie befriended the Native people and spoke Chinook, their trade language in the Pacific Northwest. In 1860 he declared that the Indians held aboriginal title to their land and this must be recognized by law. He forced legislation to ensure Native women shared in the estates of their white partners, married or not.

But Matthew Begbie wasn’t American. He was English. The British appointed him chief justice of the Crown Colony of B.C., then a colony of the British Empire. In no small way he helped pave the way for B.C. to join Confederation and they named things after him. Sir Matthew Begbie Elementary School in Vancouver. Mount Begbie. Begbie Summit. Two lakes and a creek. And in New Westminster a street and public square. But the big thing was that statue in front of the city’s courthouse and there was another one in Vancouver outside the Law Society of B.C. It was fitting because he pretty much wrote the law in these parts and for 125 years everything was fine.

In 1958 the National Film Board of Canada produced a docudrama – The Legendary Judge – that started this way: “He was the form and substance of British justice sent out from England to challenge the wild west.” When he arrived exactly one century earlier, in 1858, he was the first and only judge in B.C.

The January 1947 edition of The British Columbia Historical Quarterly ran a piece about Begbie by historian Sydney G. Pettit who described his subject: “Fearless and incorruptible, he made his name a terror to evil-doers who, rather than face his stern and impartial justice in the Queen’s court, abstained from violence or fled the country, never to return.”

Directly below the title of that publication were the words: “Any country worthy of a future should be interested in its past.”

Indeed.

Begbie was a lawyer in London before arriving in B.C. Remaining a judge for 36 years, he’d be responsible for much of B.C.’s early legislation – the Aliens Act of 1859, Gold Fields Act of 1859, Pre-emption Act of 1860 – statues involving immigration, commerce and settlement. But one case in particular sealed his fate and it was done in a way that only a self-flagellating country like Canada could conceive.

Gold discovered in the Fraser Valley led to the arrival of thousands of miners and that changed everything. Salmon fishing was vital to the Indigenous who fought inter-tribal wars over it. One of the worst massacres ever to occur in what is now Canada happened in 1745 in the Dakhel village of Chinlac. The dispute was between the Dakhel and neighbouring Tsilhquot’in, or as they were known, Chilcotin.

An account of the atrocities, written by a priest, describes in vivid detail how the Dakhel chief returned to his village only to see the bodies of his two wives and children hanging on poles. The children’s bodies had been ripped open and spitted through out-turned ribs like salmon drying in the sun.

The message? Don’t mess with salmon.

When the miners came they washed gravel through their mining sluices, diverting waterways, impacting salmon spawning grounds. Whether that caused the Chilcotin War or not, it led to the deadliest attack against whites in western Canada.

Ever.

In 1864 a crew started building a road through Tsilhqot’ territory. Over several days, a score of killings took place, nine in one fell swoop on April 30 when the men were “shot or bludgeoned to death in their tents” as they slept. The war party then moved on and committed more murders. When it was over, 21 workers and settlers were dead, their bodies mutilated.

There are accounts of what happened. The colonial government set up a search party and found the alleged perpetrators, including their leader, a chief named Klatsassin.

Begbie was the trial judge and court records exist. A jury trial resulted in guilty verdicts for five of eight men charged with murder. Later, a sixth man was found guilty. Back then such a verdict carried the death penalty and the six were hanged.

From then until 1993 there was no ‘controversy’ about Begbie. But that year a report of the Cariboo-Chilcotin Justice Inquiry examined the relationship between Indigenous People and the justice system, and called for a posthumous pardon of the six chiefs. More than two decades later, in 2014, B.C. Premier Christy Clark issued an apology. She said the chiefs were “fully exonerated of any crime or wrongdoing.”

Then the snowball effect. A plaque posted near the Fraser River in Quesnel, B.C., said the chiefs were wrongfully hanged. In 2015 we had the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report, in 2018 Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s public apology, and in 2020 the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement. With that came the rising woke slant on history with everything Indigenous deemed good and everything white, colonial and settler bad.

I looked online for details of that plaque in Quesnel and found it under the headline Legacy of the crimes of British colonialists; the website belonged to the Marxist-Leninist Party of Canada!

The floodgates now opened for Begbie being the fall guy. But not everyone saw it that way. Peter Shawn Taylor wrote in The 1867 Project: Why Canada Should Be Cherished – Not Cancelled (Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy, 2023): “The final requirement for this new narrative affirming the natives as victims is the transformation of Begbie into a villain. His punishment is to have his reputation rubbished and his name scrubbed from the province’s road maps and lobbies.”

Never mind that it was trial by jury which meant the jury decided things and, as presiding judge, Begbie’s duty was to uphold the verdict and pronounce sentence.

Or that two members of the Tsilhqot helped find those who committed the massacre.

Or that one testimony came from a Clahoose Native who said the execution of the six was justified and his own people were “nearly annihilated” by Tsilhqot’in.

Begbie still paid the price.

In 2001 the University of Victoria removed his name from the school’s law building.

In 2017, the statue of him on horseback in the lobby of the Law Society of B.C. building in Vancouver was purged, as was a plaque that read: “His 36 years of fearless and impartial service made a lasting contribution to the administration of justice in the Pacific region of Canada.”

No longer.

The Tsilhqot’in leaders who inspired this then demanded that his name be removed from all public places.

As usual, the media played its sorry role in this misrepresentation of history. When Begbie’s ‘controversial’ statue was removed from the B.C. Law Society, CTV News reported: “The society previously featured the statue of Judge Matthew Begbie, who wrongfully convicted six Tsilhquotin War Chiefs of murder in 1864, sentencing them to death by hanging.”

The city of New Westminster renamed Begbie Square and Begbie Street in honour of two chiefs who had been wrongfully hanged, and Sir Matthew Begbie Elementary School in Vancouver was given an Indigenous moniker.

Sam Sullivan is a former mayor of Vancouver. After the Law Society of B.C. in Vancouver and the city of New Westminster removed their Begbie statues, he was so incensed he made a video about the gold rush, Indigenous inter-tribal conflicts, and Begbie.

“While south of the border the U.S. Army waged a dozen wars against Indigenous people, Judge Begbie risked his life in hostile environments for a more just society,” said Sullivan. “With a legal system that owes so much to him in a province whose very existence depended on the force of his personality, one must wonder if the justice he worked so hard for was done.”

Sullivan says the Law Society made its decision to remove the Begbie statue “in secret.”

Legal historian Hamar Foster is a law professor emeritus at the University of Victoria. He contributed an essay for the book Voicing Identity: Cultural Appropriation and Indigenous Issues (University of Toronto Press, 2022), his subject the Law Society decision to remove the statue. Foster’s essay made several points:

The Law Society report said Begbie “found (the Tsilhquot’in warriors) guilty” of murder and “ordered their execution,” but this was not so since the jury found them guilty and death was the mandatory sentence for murder.

The colonial governor, not Begbie, had discretion to commute the death sentences.

Said Foster: “I spoke to a number of people, and almost everyone, lawyers included, whose only source of information about the events of 1864 was the media, believed that the decision to convict and sentence the men to hang was Begbie’s, and his alone. Which is not true. Some also did not know what the hanged men were alleged to have done.”

The Law Society report said Begbie “epitomizes the cruelty of colonization” and his relationship with Indigenous people was “negative.” Not true, says Foster. What does he conclude about Begbie?

“His record is much better than that of his contemporaries in Australia, the U.S., and the rest of Canada. And when his career is subjected to close examination, he stands out as both insightful and sympathetic when compared to most British Columbians of his day.”

Foster says the Chilcotin had legitimate grievances – not being consulted about the road, the threat of smallpox, sexual assaults against their women. As for the 21 white men killed and mutilated, he said the Chilcotin thought of this as warfare. But he has a beef with how the Law Society made its decision about the statue. He said the full membership wasn’t consulted and the benchers rendered the decision on an “incredibly one-sided report.”

Author David R. Williams wrote a biography on Begbie called The Man for a New Country (Gray’s Publishing Ltd., Sidney, BC, 1977). Said Williams: “No other judge in Canada combines an historical reputation of national proportions – Canada might, without Begbie and a few others, have had its western boundary at the Rocky Mountains.”

So, if not for Begbie, British Columbia as we know it today might not exist. Yes, if he was American there would be a movie. But in Canada we do things differently.

This excerpt is taken from Sleepwoking by Jerry Amernic, now available on Amazon

Our website is the place for the latest breaking news, exclusive scoops, longreads and provocative commentary. Please bookmark nationalpost.com and sign up for our newsletters here.

Comments

Be the first to comment