Unpublished Opinions

Indigenous voices put land rights and sacred land on the reconciliation agenda

Non-Indigenous Canadians seeking to know what reconciliation looks like must heed the voices of Indigenous writers, artists and activists speaking their truths about a core value settlers need to honour: the land.

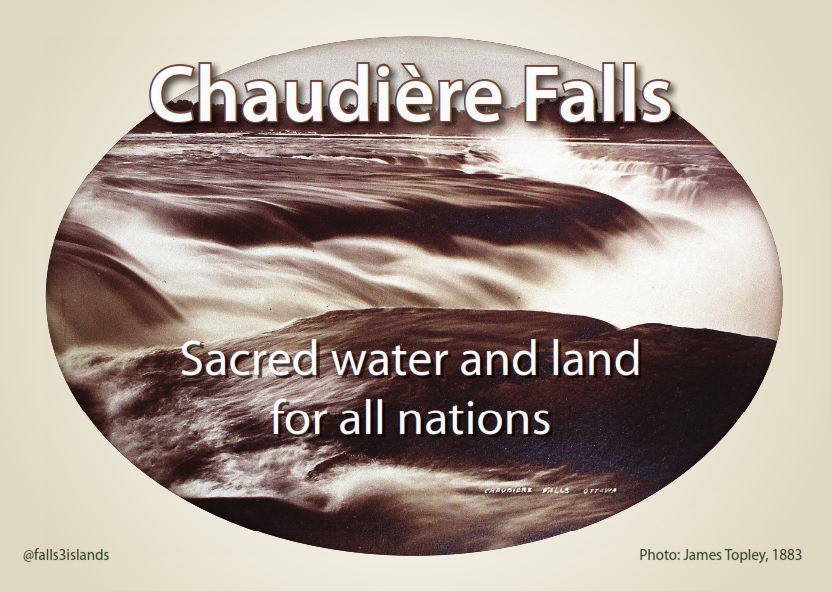

Islands in the Ottawa River currently threatened by two corporate profit mongers sit on unceded, traditional, and sacred land. All of these terms describe the land rights that Indigenous people are asserting as they speak in defence of Chaudière, Albert and Victoria Islands, and the massive waterfall that animates this deeply spiritual place.

In 2015, nine Algonquin chiefs asserted land rights to the sacred site Akikodjiwan. Their request to be heard by federal, provincial, and municipal officials has mostly been ignored, although two recent meetings with the National Capital Commission (NCC) point to some accommodation by that federal body. The NCC knows only too well that the massive condo project it has supported since early 2015 may be on shaky ground, and that the duty to consult Indigenous groups is one it cannot shirk. Taking responsibility on questions of land is paramount in the new world of reconciliation that Canada says it will embark on.

Christian churches, too, are coming to know that an ecumenical announcement of March 30, which promises actions that will uphold the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), must be based on more than atonement or morally motivated and gracious generosity.

Anishinabe comedian and podcaster Ryan McMahon told a radio interviewer on Easter Sunday that the way settler Canadians view reconciliation needs to move beyond "a basic life skills program." In this 7-minute interview, he focuses on the need for settlers to first decolonize—their minds, hearts and some deeply held beliefs—before they proceed to reconciliation.

"Decolonization starts with land. It starts with the question of land," McMahon said. Too often, he added, the conversation about reconciliation focuses on kindness and understanding, instead of asking hard questions about land, sovereignty, and treaty implementation, CBC reported.

A timely editorial from the Times Colonist has taken a recent pilgrimage by an Anglican bishop in support of reconciliation as an example of how atonement may be the start of something that looks like reconciliation. It then cites McMahon's statements as a different side of that coin: one that is much less about settlers being "nice" and a lot more about them advocating for systemic change.

What is more precious to settler Canadians than private property? What is the Canadian Crown prouder of than the ceded and unceded Indigenous lands now under its control? The Algonquin chiefs have cited sections of UNDRIP that refer to land rights in their declarations related to the Chaudière waterfall and islands sacred site Akikodjiwan.

For their part, the two corporations proposing to build 2,000 condos on tiny islands in the Ottawa River are asserting the kinds of rights that oil and mining companies assert when they convince governments to support resource extraction projects. Economic growth and tax revenues entice greedy governments to proffer support. But what if the unceded Algonquin territories of Chaudière and Albert Islands, which constitute half of the sacred site Akikodjiwan, are not for sale?

Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg Elder, Albert Dumont, titled his March 28 blog post Asinabka: Impossible to buy! The same day, Metis youth activist, Gabriella Fayant released her own post on the subject, calling it Free all Sacred Sites.

Their strong voices decry the desecration of Indigenous unceded lands that hold spiritual significance. Like Ryan McMahon, they are urging settler Canadians to move beyond sympathy to a deeper understanding of what is at stake.

At the church-sponsored event in support of UNDRIP, Elder Shirley Williams told priests, bishops, and lay people that "the land is our church." She also spoke of how water holds deep power and significance.

Many Indigenous people are determined to ensure that the business consortium called Dream Windmill, and the government bodies that support it, do not desecrate this sacred site and the waterfall that protects these islands. Who in the settler community will stand with them?

Comments

Be the first to comment