Source Feed: Walrus

Author: Martin Lukacs

Publication Date: April 25, 2025 - 13:30

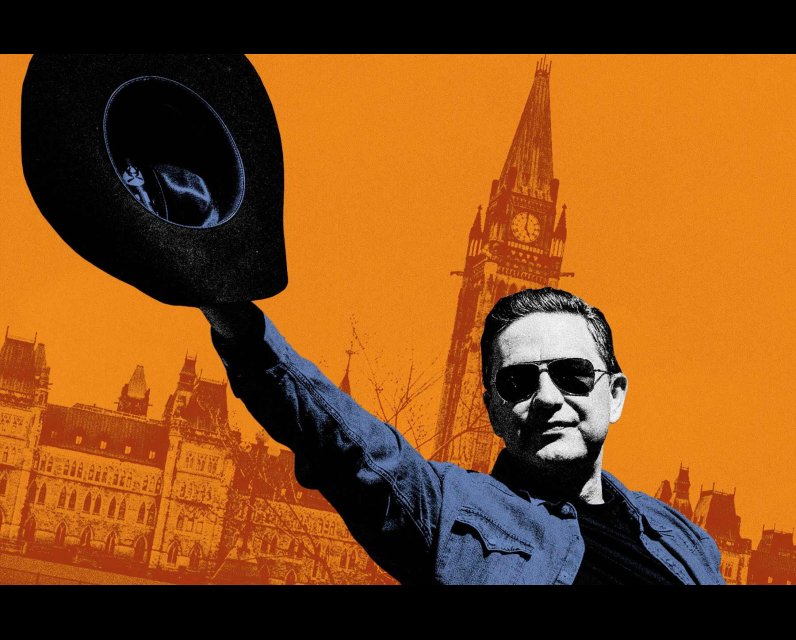

The Book That Built Pierre Poilievre

April 25, 2025

In 2019, the CBC sent an election survey to Ottawa-area members of Parliament and candidates, asking what event, book, or song had made the biggest impression on their “political thinking.” Some cited growing up in a close-knit rural community. Others cited Margaret Atwood’s novel The Handmaid’s Tale or the music of the Tragically Hip. Pierre Poilievre, then MP for the riding of Carleton, the Conservative finance critic, and a rising star in the party, took a different tack. He chose what had, for two decades, been his political bible: Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom.

Poilievre had first come across the book as a fourteen-year-old teenager growing up in Calgary. Out of commission from a sports injury and bored, he tagged along to one of his mom’s Progressive Conservative meetings. “And I just started reading a lot of left-wing books and commentary, and was very, very briefly persuaded by that,” he recounted many years later. Then he stumbled upon Friedman’s book. It made a profound and abiding impression.

Many years on, he described the book as “a transformative resource on the power of the free market and free enterprise in our society.” Over his own career, Poilievre has leaned on it exactly that way, mining it for analysis of the workings of the economy and society and how to go about changing them. From Poilievre’s earliest writings to his most recent viral videos, you can trace Friedman’s footprints.

Capitalism and Freedom is something of a Rosetta Stone, the key to unlocking an understanding of many of his views: his aversion to progressive taxation, his disdain for social programs and public housing, his animosity against labour unions, his opposition to diversity initiatives, and his dire warnings about inflation. It has deeply shaped his worldview, his perspective on Canada’s challenges, and the political program with which he hopes to reshape the country if he becomes prime minister.

In gravitating toward Friedman as a young man, Poilievre hadn’t picked any old obscure academic. The American economist was one of the most influential economists of the last century, widely considered the godfather of today’s corporate-dominated globalized economy.

At the start of his career, Friedman was a lonely voice. In the post-depression era, a Keynesian tendency that markets could not be left to their own devices reigned supreme. In Canada, in the face of powerful labour movements and the growing popularity of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (the precursor to today’s New Democratic Party), governments reluctantly began providing citizens with unemployment insurance and family allowances. By the early 1960s, pensions and health care followed.

Friedman and his own guru, Austrian philosopher Friedrich Hayek, thought otherwise. Hayek believed that interference in the market was a slippery slope toward authoritarianism. The free market was a perfect scientific system, and if individuals were allowed to pursue their self-interest, it would create maximum benefits for all. But if the market did not function as their mathematical models indicated it should, the fault lay with the interfering hand of government. (This evoked a model of a free market that has never actually existed—governments have always used their power to create and enforce markets.)

Hayek, Friedman, and other neoliberal thinkers saw distorting interference everywhere: in governments capping prices, establishing public education and medical care, and even in permitting the existence of labour unions. Friedman was convinced that introducing such distortions into a supposedly self-equilibrating market would actually hurt rather than help people, and that wiping them away should be the government’s mission. In Capitalism and Freedom, his first best-selling book, Friedman distilled this mission into a policy playbook.

Governments would need to sell off any publicly owned assets to be run instead by private companies. They would need to remove all regulations that obstructed corporations from accumulating profits. And they would need to drastically reduce social programs by cutting taxes and slashing spending. Friedman included a list of items in Capitalism and Freedom, stretching across multiple pages, that would not exist in a supposedly free economy: a minimum wage, rent control, public housing, the postal service, old-age supports and retirement pensions, and even national parks. (To underline the point about the importance of sweeping cutbacks, privatization, and deregulation, Friedman added a notorious note: “This list is far from comprehensive.”)

It amounted to a reversal of everything that had been gained by the workers’ movements since the Great Depression.

By the 1970s, these ideas found a much ready audience. The corporate class in the United States and Canada was chafing over their uneasy post-war compromises. With militant unions, rising expectations, shrinking profits, and higher inflation, their tolerance for taxes, unions, and regulations petered out.

In Canada, corporate executives, who had been alarmed by some of the activist inclinations of Pierre Elliot Trudeau’s government and NDP leader David Lewis’s attacks on “corporate welfare bums,” began funding think tanks, like the Fraser Institute, to spread the word of the free-market rule book. What followed, starting in the early 1990s when Canadians were inundated with warnings that the country was about to hit a debt wall and that drastic measures were needed to get spending under control, was the real world impact of Friedman’s rule book: incredible profits for a privileged few, the gutting of the middle class, and exploding inequality.

But victors have always wanted more. In a later edition of Capitalism and Freedom, Friedman would distill a strategic lesson Poilievre seemed to take to heart. The duty, he wrote, is “to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable.”

In the mid-1990s, Poilievre deepened his ideological commitments. As a high school student, he attended seminars hosted by the Fraser Institute, which targeted university campuses in a major recruitment effort by offering large cash prizes for student essays. In major cities across Canada, their day-long events involved a mix of talks by Fraser Institute staff and invited university lecturers, as well as free lunch and copies of free books like Friedman’s.

Poilievre was younger than the other attendees, but he was precocious and smart. He was soon drawn into Reform politics, a predecessor to present-day Conservatives, and found he had a knack for working the phones for local candidates. He volunteered in call centres for the party, attended meetings, and became a delegate at national conventions. As a fifteen-year-old, he found his way into Reform MP Jason Kenney’s election campaign. Poilievre’s biographer, Andrew Lawton, relates how Kenney was “astonished” by Poilievre’s “genius” skills on the phone and his personal sales pitch describing Kenney as a “tax fighter.”

After graduating, Poilievre enrolled at the University of Calgary and began speaking to larger crowds at the campus speaker’s corner. He also joined the Reform Club. Lanny Westersund, vice-president of the club at the time, recalls travelling with Poilievre across the backroads of the province to fundraise so that students could attend regional and national conventions. When the university student union banned the Reform Club for poster infractions, Poilievre and his friends organized a melodramatic “funeral for democracy.” The stunt made headlines and was a taste of Poilievre’s knack for attracting media coverage.

In his late teens, Poilievre had already taken to publishing op-eds in local Alberta newspapers. In the Calgary Herald, he savaged the Liberal government for its reforms to the Canada Pension Plan (not usually an abiding teenage concern). In another, he praised Alberta’s social services minister, Stockwell Day, for putting the “government on a diet” to support “a pro-growth flat tax.” He also kept up his advocacy for “school choice,” writing in another Calgary Herald op-ed in favour of government-funded vouchers for parents to cover the cost of private education, a surefire way to undermine the public system.

Poilievre was always a “good pitchman” who was hard to say no to. But he was just as likely to be found with his nose in Milton Friedman’s A Monetary History of the United States. One former student says the continuities are uncanny: “The guy you see giving speeches right now is the same guy that you would have seen giving speeches when he was nineteen years old,” he said. “Even the content. Phrasing. Pierre’s views have not really wavered.”

Most people outgrow their teenage intellectual preoccupations. But Poilievre’s views have not evolved, and he has preached only from Friedman’s book. The influence pops up again and again in his speeches in Parliament, in op-eds, in catchy viral videos, and even in Poilievre’s memes.

Perhaps the most unyielding principle that Poilievre has drawn from Friedman’s work is his view that one should never have the government do what can instead be done on the private market. Any act of collecting taxes and spending to create social programs or public works is a forceful imposition, crowding out what people might instead do freely on the private market.

Ryan Kelpin, the scholar who has closely explored Poilievre’s intellectual debts to Friedman, points out that Poilievre has restated this frequently, often in phrases nearly identical to Friedman’s. “We should not expand government into areas people can decide upon and act out on their own volition,” he said in Parliament in 2017, echoing the same language from Capitalism and Freedom. A few years later, Poilievre cast this in even more stark terms: “Everything the government does, even the good things, is done by the coercive force of taxation, a gun to the head.”

Surely, however, most Canadians are happy with the government “forcibly” imposing medical care, pensions, standards in handling food and sanitation, minimum wages, and clean public drinking water, especially when “imposed” as a fulfillment of the democratic will of citizens. The alternative, of course, was that these would remain commodities only available to those who could afford them, which, indeed, is the inescapable logic of Friedman’s and Poilievre’s position.

Kelpin points out that Poilievre subscribes to Friedman’s leviathan model of the state. In an interview where Jordan Peterson asked what Poilievre learned from Friedman, he invokes this theory, describing how special interests and bureaucrats benefit most from government programs. “So when this big beast called government gets bigger and more powerful, those who have the ability to steer that beast are the ones who are going to profit from it.”

This view has driven Poilievre to certain positions—rolling back taxation, stopping programs of redistribution, and withdrawing the state from providing for its citizens. In an article in the Financial Post in 2018, Poilievre called the welfare state “truly horrific.” It “survives only by keeping people poor” and “engenders a self-serving bureaucracy whose survival depends on a growing clientele of poor welfare recipients. To end poverty, this bureaucracy would have to put itself out of business, something it will never do.”

Another policy proposal Poilievre has borrowed from Friedman is for a universal basic income, but not as a means of redistributing money to ensure a guarantee of a dignified life. Poilievre described the Ontario Liberal government’s basic income pilot project in the 2010s as “feeding the beast more money and more people.” Instead, he says a universal basic income should be a route to “replacing the entire welfare state” with “a tiny survival stipend for all low-income people to be gently phased out as they earn money.” This would come with a catch: “Governments would pay for Friedman’s basic income by eliminating all other programs, including housing, drug plans, child care, and the bureaucrats who administer it all.”

Friedman’s core philosophy has even seeped into Poilievre’s views on family life, Kelpin notes. Poilievre fondly cites his adoption as an infant using Friedmanite language, saying that “voluntary generosity among family and community are the greatest social safety net we can ever have. That’s kind of my starting point.”

In the summer of 2022, as inflation put a major financial squeeze on most Canadians, the director of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation asked Poilievre in a YouTube interview what book on economics he would recommend to viewers. Rooting around the library behind his desk, he pulled out a thick volume and waved it at the camera; it was a copy of Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s A Monetary History of the United States, its pages brimming with sticky notes.

The book provides a one-size-fits-all explanation for inflation, claiming it is caused by “too much money chasing after too few goods.” Poilievre has relied on this theory for years. He is fond of invoking Friedman’s idea that, because inflation reduces the purchasing power of money, it is like a de facto tax. “Taxation without legislation” is a line Poilievre regularly quotes. When the latest round of inflation hit Canada in 2021 and became a national focus, Poilievre’s regurgitated Friedmanite talking points took on new significance in his constant attacks on Justin Trudeau and the Liberal government.

“This was all so predictable,” Poilievre said in the House of Commons in 2023, in an ode to Friedman. “Rapid increases in the quantity of money produce inflation. So said the greatest expert on monetary economics in the history of the world, as recognized by the Nobel Committee.”

It was a simple and compelling explanation—and it was factually incorrect. In the 1980s, central banks, influenced by Friedman, strictly applied the idea and tried to control the expansion of money. These policies directly sparked a damaging global recession, forcing a rethink among most economists and central bankers.

Inflation is far more complex and can have different causes, sometimes spending and in other cases, high wages, high profits, or energy costs. But as inflation peaked in Canada, Poilievre simplified Friedman’s theory even further by blaming Trudeau for single-handedly causing inflation by “printing” and spending too much money, with the Bank of Canada acting as the prime minister’s “personal ATM.”

As economist Jim Stanford pointed out, the particulars of this were wrong too; most money in Canada is not printed. Much of it is created by private banks rather than the Bank of Canada, and the money supply was actually shrinking, even as Poilievre’s attacks reached a fever pitch.

According to Stanford, these Friedmanite views came across as particularly dogmatic because the inflation that gripped the country over the last few years was sparked by the consequences of lockdowns and other supply disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as major profiteering by corporations that took advantage of supply chain shocks to boost their prices and pad their margins.

Stanford also noted an irony. In 2022, Canada’s central bank—run by bankers whose views overlap with some of Friedman’s—embarked on a course of high interest rates, putting a chill on borrowing and spending, suppressing workers’ wages, and throwing people out of employment while driving inflation down. But that didn’t bother Poilievre. Guided by his Friedmanite north star, he wanted them to chart an even more fundamentalist course: refusing to print money to buy government bonds. The bonds helped the government borrow cheaply so that it could help people survive the pandemic. If actually implemented, Stanford says, Poilievre’s deep aversion to government spending would more surely than anything have led to a “full-blown market crisis.”

In recent years, Poilievre has been cautious about explicitly spelling out the full implications of such views, but in unscripted moments, the mask has occasionally fallen away. During a press conference at a Vancouver gas station in the spring of 2024, this is how Poilievre responded to a question about federal government spending with a line straight from Friedman verse: “I’m very hesitant to spend taxpayers’ money on anything other than the core services of roads, bridges, police, military, border security, and a safety net for those who can’t provide for themselves. That’s common sense.”

The overwhelming majority of Canadians would likely find such a vision for the country far from commonsensical. Instead, they’d find it incredibly bleak to have a state stripped down to providing only “core services.” Poilievre did not explain what would become of the universal social programs and services that most Canadians hold dear: health care, education, pensions, public transit, housing, parks and pools, community centres, or support for the arts. These are the publicly provisioned elements of a liveable society that ensure culture and care are accessible beyond those who can personally afford them.

None appear to figure in Poilievre’s conception of the government’s role. We could call this thinking neoliberal nostalgia, a desire to turn back the clock to when the state’s role was limited and often violent: paving the streets, sending soldiers to fight imperial wars abroad or put down striking workers at home, dispatching police to protect property or clear the destitute off the streets, and offering some basic alms to the poor. It was a vision of society that existed before the hard-fought struggles of organized workers in the ruins of the Great Depression and World War II, when children died in the crib because of preventable diseases, the average lifespan was fifty-eight years, and people worked intolerably long weeks.

This vision of Canada, ideologically hardline, would continue to steer Poilievre’s work as he headed to Ottawa.

Adapted and excerpted from The Poilievre Project: A Radical Blueprint for Corporate Rule by Martin Lukacs, with permission from Breach Books. Copyright © Martin Lukacs 2025. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.The post The Book That Built Pierre Poilievre first appeared on The Walrus.

Prime Minister Mark Carney urged Israel to allow the World Food Programme to work in Gaza, saying food must not be used as a "political tool," hours after the UN agency said it had run out of stocks due to a sustained Israeli blockade on supplies.

April 25, 2025 - 21:44 | | CBC News - Canada

Multiple attendees have alleged that security at Prospera Place used excessive force on fans during the show’s opening act.

April 25, 2025 - 21:27 | Victoria Femia | Global News - Canada

WorkSafeBC confirmed it is investigating the incident that happened at approximately 3:30 p.m. on April 11 at the site located in the 600 block of Herald Street.

April 25, 2025 - 21:25 | Amy Judd | Global News - Canada

Comments

Be the first to comment