Source Feed: Walrus

Author: Soraya Amiri

Publication Date: May 26, 2025 - 06:31

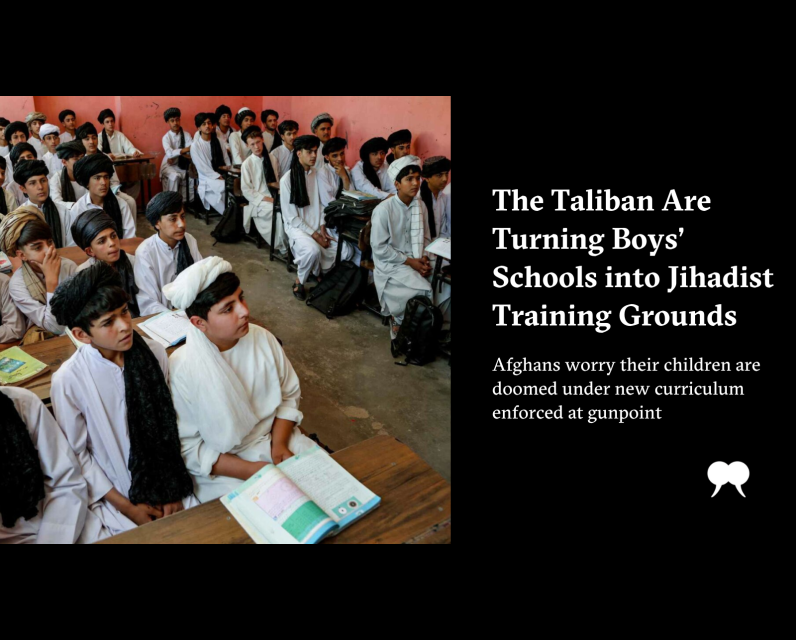

The Taliban Are Turning Boys’ Schools into Jihadist Training Grounds

May 26, 2025

When the Taliban seized power in Afghanistan in August 2021, Aman and Zaynab encouraged their children to keep going to school. (For their safety, the couple asked that pseudonyms be used for this story, and only first names.) At first, their two older boys, who are now fifteen and thirteen, resisted. Their favourite subjects, including English and science, weren’t being taught anymore, and their new teachers were rough with them.

Aman and Zaynab felt school was still worthwhile, even under the new circumstances. Both are former teachers, and Aman served as a district education director in one of Afghanistan’s provinces. But late last year, the family fled the country. Their primary reason: school had simply become too dangerous for their kids.

Within weeks of their takeover in 2021, the Taliban, who now form Afghanistan’s de facto government, began making sweeping changes to school curricula. They cut courses they considered westernized and, in their view, anti-Islamic, such as civics, art, cultural studies, and human rights. They banned girls from continuing past grade six, and they segregated classrooms. Taliban soldiers patrolled schools, carrying guns, to make sure these orders were followed.

Taliban authorities fired most female secondary-school teachers or stopped paying them until they were forced to quit, often replacing them with underqualified men. In many cases, these were ulema, or religious scholars, with few teaching credentials. Male teachers and administrators were told to grow out their beards and wear traditional dress, including turbans.

Any remaining female teachers were forced to cover their faces and told to teach only the Quran. When Zaynab tried to comply, she was told she wasn’t doing it correctly. After a year, she left her job. She continued teaching girls in secret for some months but stopped after Taliban authorities began following her and asking questions.

Over the past four years, there has been widespread condemnation from Afghans and the international community about the crushing barriers to education girls and women in the country face. What’s less visible, though perhaps just as concerning, is what kids are learning in school. Particularly boys.

Aman and Zaynab began to notice changes in their sons. Their family is Hazara, part of a predominantly Shia minority in Afghanistan, and initially it bothered Shams (who also used a pseudonym), their oldest son, that the Taliban forced students to learn only Sunni teachings. Teachers encouraged the kids to fight for the Taliban one day. But over time, Shams began to grow accustomed to the religious lessons. He even made friends with Taliban members outside of school.

At home, he and his brothers listened to Taliban-sanctioned songs that celebrated the group’s so-called jihadi victories. They would tell their younger sister that she didn’t need to go to school since she wouldn’t be allowed to continue her education anyway. “It was hard for me” to hear that, says Zaynab. Around them, other families complained of similar behaviours, with boys preventing their sisters from going to school and telling them to cover their faces.

Shams asked Aman to buy him a turban and declared his intention to grow out his hair, apparently trying to imitate his new friends. For Aman, this was especially alarming. (Aman had been forced to grow out his own beard and to comply with the Taliban’s dress code at work.) He knew of high school–aged boys who’d dropped out of school to join the Taliban as fighters and, as they put it to him, work “for Islam.” He and Zaynab worried their boys might be compelled to do the same.

In the early days of the Taliban’s return to power, Aman had tried to leave his job, but that proved risky; Taliban officials questioned why he would work for the previous government but not for them. The threat was implied: if he quit, that might be a sign of disloyalty and cause for punishment. So he stayed on.

Whenever he felt reasonably confident that no Taliban representatives could hear him, Aman would encourage teachers and students not to lose hope, to continue the study of subjects like math and English. He still believes that the Taliban won’t last forever, that Afghanistan may one day be free of them again.

That belief wasn’t enough to keep him and his family in the country. Last September, they fled and now live abroad. Because they aren’t registered refugees, Aman and Zaynab still can’t send their kids to local schools. Instead, the children are enrolled in online courses, learning English and computer science. They’re starting to develop an interest in their studies again and have expressed their intentions to become doctors and teachers.

Aman and Zaynab haven’t yet found work, nor have they succeeded in applying for resettlement in another country. But even as he tries to chart a path forward for his family, Aman still worries about the students he was responsible for back home. “My head is still in Afghanistan,” he says.

Through their draconian decrees, the Taliban have already destroyed the aspirations of girls and women, he says. That’s half the population. The other half may also be doomed if nothing changes. “Now I’m very worried the new generation will be believing the Taliban ideology,” he says. “After one or two years, if the regime is not finished, there’s no hope for the new generation.”

The Taliban’s school curriculum is essentially a tool for radicalization, says Mirwais Balkhi, who served as Afghanistan’s acting education minister from 2018 to 2020. Now based in the US, Balkhi is editor-in-chief of the University of Afghanistan’s Journal of Diplomacy and International Studies and a member of Princeton University’s Afghanistan Policy Lab.

While private schools, which typically cost between $90 and $200 in annual tuition, retain limited control over their affairs, public schools are required to follow a Taliban-imposed curriculum. In high school, any surviving subjects, such as the sciences, are being warped to reflect the Taliban doctrine. (A spokesperson for the Ministry of Education was unavailable for comment.)

“The overall objective is not to teach chemistry, not to teach physics,” says Balkhi. When a religious scholar teaches chemistry, he says, “he talks about the chemistry of the human being, which is created by God, and [how chemistry] is mentioned in some of the Quran and Hadith quotations.” Some Taliban-appointed teachers encourage students to “reject the modern sciences,” which in the Taliban’s view are “based on illusion, not on reality,” and contradict religious teachings. They may promote the idea that scientific achievements, such as the moon landing, are hoaxes.

These teachings aim “to extend a Taliban ideology all across Afghanistan, [and] through that to extend the survival of the Taliban,” says Balkhi. The new regime has introduced competitions in which students are quizzed on aspects of the Taliban. Even the language of instruction is weaponized: Ahmad Gardezi, who teaches Persian (Dari) at a public school, says government authorities send schools materials mainly in Pashto, the Taliban’s preferred language. (He also asked for a pseudonym.) He worries the Taliban might eliminate Dari from the curriculum altogether.

The current school curriculum emphasizes how Afghans fought against the British, the Soviets, and the US and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, resisting imperialism; democracy is presented as antithetical to an Islamic state. Suffusing the population with what Balkhi describes as a rejectionist mentality, the Taliban are guaranteeing that Afghanistan will have “a society without any competency, without any skill, without any . . . taste of modern education.”

“It is not worrying because people will learn about Islam,” says Orzala Nemat, a UK-based scholar focused on political ethnography. “But it is worrying because, in addition to Islamic studies, these are spaces that allow radicalization to happen.”

While not all teachers working today are radicalized, says Nemat, there are indications that, in many schools, “the leadership is in the hands of the Taliban,” whose members were themselves educated in militant madrassas, or religious schools, that over the past few decades were breeding grounds for radicalized fighters and suicide bombers. “That means that whatever the beliefs of the top leadership of the madrassa, that will spread to the teachers, and through the teachers, it will also spread to . . . boys who are attending these educational programs,” says Nemat.

Between 2020 and 2024, the number of madrassas across the country shot up from about 1,800 to 22,000, with more still being built, says Balkhi. (According to some reports, the pre-Taliban number of madrassas may have been much higher—around 5,000.) Falling under the purview of ministries such as the one for hajj and religious affairs, many madrassas are established by mullahs and funded in part by wealthy donors looking to win favour among Taliban leaders. Girls are permitted to attend madrassas at any age, though it’s not clear what they’re taught. To encourage enrolment, the Taliban cover tuition costs.

In the past, madrassas focused on religious teachings, says Nader Nadery, a human rights activist and a visiting fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. Because madrassas functioned like boarding schools, they were often a way for poorer families to ensure their children were housed and fed while they also learned to read and write. Now, however, there are more and more jihadi madrassas emphasizing military training to churn out fresh, zealous recruits for the Taliban’s security forces and Ministry of Defense. While Afghanistan is not currently at war, says Nemat, such jihadi madrassa recruits could one day be persuaded to join suicide squads, should the need arise.

To Nemat, having little access to female professionals is a driving factor in becoming Taliban. The group is “paranoid” about women’s empowerment, she says, precisely because few of its leaders were exposed to women during their own upbringing and training. Many were orphaned during the anti-Soviet era and raised in all-boys madrassas, where they lived away from their extended families and rarely encountered women decision makers, she says. She’s seen first-hand how, when young madrassa students met her, they were incredulous at the idea that women could be educated and eloquent.

Child abuse is “not a new phenomenon in madrassas and schools,” says Nemat. (According to a 2023 Human Rights Watch report, children are regularly exposed to corporal punishment in the classroom—an issue that predates the Taliban takeover but has since worsened.) What’s particularly concerning now, she says, is that there is no regulatory body to address such allegations. While the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs contains a child welfare department, it rarely takes action against mullahs who run madrassas, since they are generally regarded as “good people,” she says.

One private-school director, who asked not to be named for safety reasons, says madrassa students are often taught by high-ranking Taliban officials and promised government jobs upon graduation. Some madrassas serve as post-secondary institutions, where students can receive undergraduate or even master’s degrees on an expedited timeline. These degrees, the school director says, give madrassa graduates an unfair advantage over students pursuing a more typical university education. (According to Nemat, the Taliban also oppose the idea of Afghans going abroad for their university education.)

Some of Afghanistan’s education woes predate the Taliban. When Balkhi was education minister, around 3.7 million children were out of school, largely due to poverty and conflict; many families sent their children to work instead. In some rural areas, educating girls wasn’t seen as the main priority. There were fewer women teachers at the time—which may have served as a barrier for families who didn’t want their daughters being taught by a man.

To try to address these gaps, Balkhi says, the former Ministry of Education recruited women teachers, even those who had an education only up to grade twelve, and built all-girls schools. They also launched a campaign to convince tribal families in rural areas that girls deserved an education, and Balkhi recalls one man who reported travelling twelve kilometres every day to take his two daughters to school. Through these efforts, the aim was to build “the thirst for education” all across Afghanistan, says Balkhi.

But now, the Taliban’s attitudes to education are becoming more deeply entrenched in Afghanistan’s social fabric. Balkhi points out that when the Taliban first came to power, in 1996, they ruled Afghanistan for five years. Even after the US-led invasion that temporarily defeated the Taliban in 2001, some civilians still exhibited what Balkhi describes as a Taliban mentality—for example, punishing young men who didn’t grow out their beards. As the current regime approaches four years in power, its effects are more far reaching, in part because the Taliban have embraced social media, using platforms such as WhatsApp and Telegram to spread and reinforce their extremist views.

“It’s difficult to say what is the full justification” for the Taliban’s education policies, says Nemat. “No one has an explanation, including Taliban.” Some of the group’s leaders insist they aren’t against a secular education, and that the country needs engineers and other professionals. Yet, to Nemat, the Taliban seem bent on holding back progress in the country, especially through systematic discrimination against women.

Even if girls’ secondary schools were to reopen tomorrow, says Nemat, “that will not be a simple celebratory time for us, because we will not be able to get a clear grasp of what subjects students will learn when they attend these schools.”

Balkhi has already observed how some girls have begun changing their mentalities, giving up on their own education. With male family members gaining even more privileges than before and becoming the sole breadwinners, “it naturally gives dominance to the boys of the family.” The private-school director says he’s noticed that boys are increasingly being persuaded that girls are meant only for marriage. He says he can foresee all of Afghanistan eventually becoming like the Taliban and all schools being run like madrassas.

Sometimes, says Balkhi, “no education is better than a bad education.”

The private-school director, who oversees a number of institutions with a large student population and faculty, says teachers are divided. About half are pleased with the Taliban’s restrictions, while the rest are trying to secretly encourage their students to continue their education.

Most of the earlier textbooks are banned or have been altered to remove any pictures of living things (for some Muslims, such imagery is associated with the idolatry and iconography that many in the faith reject). Some teachers still use the outlawed textbooks but disguise the covers, giving them false titles to throw off Taliban inspectors. If caught, they can be arrested, tortured, and barred from ever teaching again.

At home, some parents are trying to supplement their children’s schooling, with mothers typically bearing the brunt of the added pressure. A number of organizations abroad provide online classes, some of which are run by members of the Afghan diaspora. (The private-school director, for example, is pointing students to Ontario-based Parry Sound International School for supplementary courses.) Balkhi estimates these programs reach around 20,000 girls, mostly in Afghanistan’s major cities and among refugees in neighbouring countries such as Iran and Pakistan. But access to such courses depends on having an internet connection, which in Afghanistan can be expensive and unreliable.

Some parents are appealing to religious scholars to put pressure on the Taliban and improve the domestic education system, says Balkhi, though it may not be enough to effect any considerable changes. “Because nowadays, any family who can afford to register their daughters in any school in Iran and Pakistan, they are migrating from Afghanistan,” he says. Like Aman and Zaynab, many of these families are fleeing not only for their daughters’ sake—“education itself is a concern because they are afraid of their boys’ destiny in the future,” he adds.

Today, there are still around 5 million girls out of school, says Balkhi. Over time, as girls and women are systematically denied an education, there will be “no educated mother in Afghanistan who can change the behaviours of the family.” Culturally, he says, Afghanistan will be doomed to collapse.

Dissenting voices are crucial in Afghanistan, Balkhi says, because they can demonstrate to the international community that the Taliban aren’t acting on the will of the people, that this education system isn’t what most Afghans want. Foreign aid organizations, says Nadery, are sometimes reluctant to criticize the Taliban’s approach to education, arguing that the focus on religion could be considered a part of Afghanistan’s culture. But, he says, “exposing a child to education that promotes militancy and violence is in no one’s culture.”

Nadery, now fifty, grew up in Afghanistan and remembers the time militants burned down his elementary school when he was in grade three. From then on, his classroom consisted of a plastic sheet spread out on the ground in the open air, with a blackboard that leaned against a tree. The teacher would sit in the only available chair. It was uncomfortable for students, especially on hotter days.

“And then my teacher, she would say, ‘Hey, I know how you feel, but look up in the sky. How far do you see? Is there something blocking your view?’ We would look up and we’d say, ‘No, it’s all sky and sky and sky . . . ’” To which the teacher would say, “‘The sky is the limit for you. Nothing can stop you, and your thinking should not be bound by any walls,’” Nadery remembers. “The philosophy around that is amazing,” he says. “What mattered was not the fancy classrooms, which we didn’t have, but . . . the quality of the teacher.”

The absence of women in the classroom has undoubtedly affected children, says Zaynab. “Without female teachers, students are more serious.” When asked to elaborate, she said, “Women listen better; men don’t listen to students as much. . . . Students can share their problems with a female teacher more easily than with a male teacher, because they feel kindness from a woman.”

Gardezi says he’s noticed among his students—all boys—that their “behaviour has become more rigid.” On the other hand, “there are also young people who have a positive mindset, but their numbers are small, and sadly, they are becoming fewer because the environment is having a strong influence on them.”

Zirak, an eager-looking fourteen-year-old and one of Gardezi’s former students, says he hopes the Taliban will change their approach to education. (He asked that just his first name be used.) He speaks in Pashto but then switches to English. “We have a lot of problems,” he says—especially, teachers who are “not clever.” He doesn’t plan to leave the country for a better education, but he does hope to switch to a private school, if his family can afford it.

“I want to learn chemistry and English,” he says, smiling. “It’s my favourite subject.” The post The Taliban Are Turning Boys’ Schools into Jihadist Training Grounds first appeared on The Walrus.

The City of Saint John is on track to welcome 22,500 new immigrants by 2030 and the city is expecting newcomers to fuel key sectors, including health care.

June 19, 2025 - 05:00 | Rebecca Lau | Global News - Canada

Prime Minister Mark Carney came under fire from Canadian Sikhs for inviting Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to attend the just-concluded G7 summit in Alberta, given the Indian government’s alleged complicity in the 2023 assassination of activist Hardeep Singh Nijjar. Read More

June 19, 2025 - 04:30 | Christina Spencer, Ottawa Citizen | Ottawa Citizen

When it comes to starting the school day, there is such a thing as “too early to learn.” Read More

June 19, 2025 - 04:15 | Christina Spencer, Ottawa Citizen | Ottawa Citizen

Comments

Be the first to comment