Source Feed: Walrus

Author: Adam Nayman

Publication Date: May 26, 2025 - 06:30

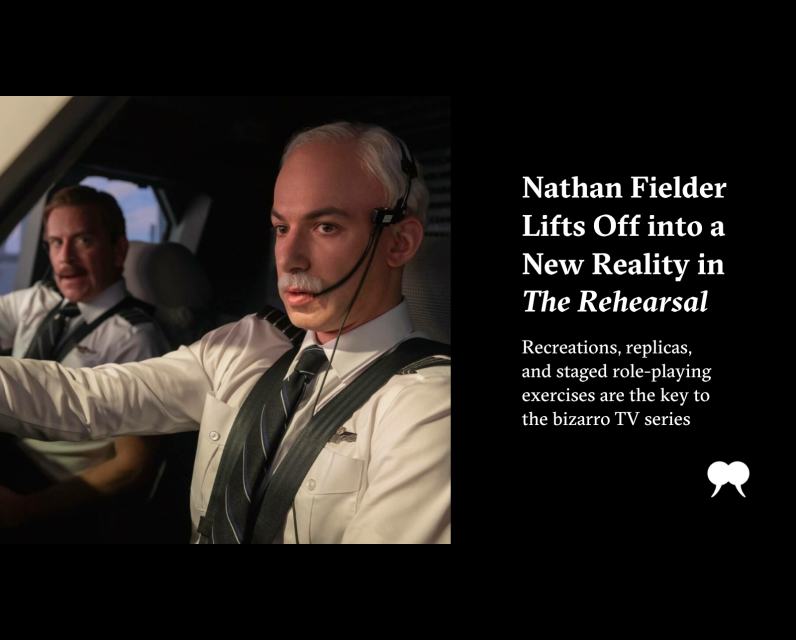

Nathan Fielder Lifts Off into a New Reality in The Rehearsal

May 26, 2025

There are plenty of A-listers with authentic pilot licences: Clint Eastwood, Harrison Ford, John Travolta, Tom Cruise. None of them, however, has ever flown a commercial airliner filled with civilians under the steady, real-time gaze of GoPro cameras mounted around the cockpit. Advantage: Nathan Fielder, the Canadian-born comedian turned conceptual stuntman, whose documentary series The Rehearsal is basically an elaborately subsidized prime-time psy-op.

Last night, Canada’s salt-and-pepper Ethan Hunt concluded the second season of The Rehearsal by operating a remaindered Boeing 737, apparently rented at a deep discount. Ostensibly, the purchase was made to help Nathan with his project of helping to prevent plane crashes; his true mission was nothing less than a Final Reckoning with the form and function of reality television itself.

It’s because of Nathan’s track record as a contemporary cult-comedy icon that he has this kind of carte blanche to treat HBO like the IMF: the International Monetary Fund or the Impossible Mission Force, take your pick. After a successful stint on This Hour Has 22 Minutes, Comedy Central gave him his own series, Nathan for You, which ran from 2013 to 2017.

That show was about helping small-business owners, many of whom were competing against corporate monoliths; now on The Rehearsal, he pursues what R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe once sang about as “conversation fear,” staging elaborate role-playing exercises in order to help iron out small talk and life’s awkward moments. Nathan pursues his goals with a single-minded determination that keeps subdividing itself in different directions. Imagine an HR-department flow chart designed by M.C. Escher, and you’re within spit-take distance of Nathan’s sensibility, formally referred to as “The Fielder Method.”

In The Rehearsal ’s first season, the Fielder Method was applied to more earthbound subject matter—staging a fake family complete with a real child for a woman considering motherhood with Nathan as the simulated father. In the second season, our hero sees whether he can apply his patented form of quasi-Gestalt therapy to the mental health of professional pilots nursing various sublimated forms of stress, trauma, and performance anxiety.

The first ten minutes of the season’s first episode, “Gotta Have Fun,” proffer a series of black comic tableaux, minimalist recreations of real-life plane crashes staged inside a flight simulator, and dialogue derived from black box recordings; the pilots are played by professional actors. Their last words before impact, recited verbatim, speak the language of a surprising non-confrontation, inhibited by awkwardness. (After asking his co-pilot to check cruise power, one captain says, “All I’m thinking of is a Philly freakin’ cheese steak and an iced tea.”)

In the cast-iron deadpan that has become his trademark, Nathan explains that a lack of communication may be the culprit behind various airline disasters. During a meeting with an apparently long-suffering safety maven, Nathan suggests that the Fielder Method may be the answer.

Absurdism takes skill, of course, but The Rehearsal ’s shivers of prophecy—the way it crept into its spring broadcast slot, trailing a series of well-publicized airline accidents and the Trump administration’s concurrent assault on the infrastructure of the Federal Aviation Administration—exist somewhere beyond evaluative criticism.

“I can’t believe they did all those plane crashes at the beginning of the year to promote season two,” reads one post on X, summing up the collective response of awed, almost superstitious bewilderment. It’s one thing to surf the zeitgeist; it’s another to seemingly predict the size and shape of the waves. Nathan, though, hangs ten on his own carefully engineered sense of distortion.

Suspending disbelief, often at a vertiginous altitude, is Nathan’s MO. Hovering weightlessly above the line dividing fiction from reality—and, just as importantly, sarcasm from sincerity—his work redefines the term “high concept.” The challenges and dynamics of interpersonal exchange—of preparing for confrontations and devising contingency plans for when they crash and burn—have been Nathan’s grind for more than a decade now.

In Nathan for You, he ended up either making a given situation worse (i.e., failing to cut costs or create cash flow) or leaving his clients so embroiled in peripheral intrigue as to render the experiment meaningless. In the first two seasons, Nathan’s efforts tended to be framed sympathetically, as noble failures, or, sometimes, as successful experiments in culture jamming, like the headline-grabbing “Dumb Starbucks” gambit that briefly turned Nathan for You into a global conversation piece.

As the show went on, however, the tone shifted more toward self-flagellation. Was Nathan a helpful good Samaritan or just desperately lonely? The feature-length finale, “Finding Frances,” unfolded as an extended fugue of mortification, pairing Nathan with his distorted mirror image, an older man (and previous Nathan for You guest star) mired in delusion and isolation, trying to track down a long-lost love.

Staged as a dual character study and paced like a slow-burn thriller, “Finding Frances” was uncomfortable enough to win plaudits from no less an anthropologist than the Oscar-winning documentary filmmaker Errol Morris. The final shot, a POV from the perspective of a drone revealing the surrounding camera crew, came as a relief, suggesting Nathan had grown uncomfortable with his own alienation effects and was perhaps taking himself out of the reality TV fray once and for all.

Not so fast. Just when he was out, he pulled himself back in, first with The Rehearsal and then with 2023’s The Curse, a superbly unnerving scripted series about the artifice of reality television. (The show was co-created by filmmaker Benny Safdie, who wrote about Nathan for You in the pages of the Canadian film magazine Cinema Scope.) In the show, Nathan played Asher Siegel, the furtive, self-flagellating husband of Instagram addict Whitney (Emma Stone), disingenuously peddling environmentally friendly “passive homes” in search of an HGTV deal.

In the end, satire converges with the supernatural as Asher gets sucked into space while Whitney is in labour. It was an ending that defied gravity, as well as conventional dramatic logic, while also feeling absolutely correct. After spending so much time trying to cultivate an appealing image, Asher’s lack of anything resembling core values hollows him out and lifts him up where he belongs—away from the reality TV cameras and into his own private purgatory.

“We are dim shapes, no more, and weightless shadow,” wrote Sophocles. It is probably a stretch to class Fielder as some kind of a neo-Greek tragedian, but he engages with the concept of deus ex machina with disarming sophistication, casting himself simultaneously as an all-powerful deity and a hapless prisoner of his own elaborately jerry-rigged devices.

The signature image of both seasons of The Rehearsal is Nathan’s laptop harness, a contraption that effectively infantilizes his MacBook in a parody of work-life equilibrium. If the not-so-buried subtext of the first season of The Rehearsal was Nathan’s burgeoning desire to become a father, played out vicariously in a controlled environment alongside an actress contemplating motherhood, his pseudo BabyBjörn visualizes the idea of puppet strings that ensnare their wearer in both directions.

Nathan’s need to obsessively insulate his collaborators against life’s uncertainties via the Fielder Method is, among other things, a pantomime of paternity—one in which father doesn’t necessarily know best. The most uncomfortable episode of season one found Nathan confronted with the unexpected attachment issues of a young boy who’d been enlisted to “play” his son on screen and was now seemingly having difficulty letting go of the relationship. The impression was of a line that had been crossed, and Nathan’s angst over his status as a “Pretend Daddy” (also the episode’s title) cut through the show’s calculus of surrogates, stand-ins, and doppelgangers; it felt real.

Determining whether ontologically wonky shows like Nathan for You or The Rehearsal are “real”—measuring how much of their ostensibly spontaneous action is scripted, or whether the people on screen are really everyday civilians or else skillful accomplices—is futile not because the answer is irrelevant but because it matters enough that the auteur has cornered the arguments in advance. “Reality,” Nathan said back on Nathan for You, “is what you make of it,” and he makes good on this premise. The set-ups of Nathan’s projects, with their open-cattle-casting calls and embedded promises of fifteen seconds of fame (temptations yoked tightly to non-disclosure agreements), are not only conducive to bizarro moments but finessed for escalation.

Nathan loves frameworks, and he also loves showing himself lurking at the edges of various construction sites, overseeing while being seen. The Rehearsal ’s much-vaunted scale replicas of a dingy Brooklyn bar, fluorescent airport lounge, stylized studio headquarters, and an oversized childhood nursery serve explicitly as prosceniums or echo chambers. They amplify their own artifice and make all the world into a (sound) stage.

I can watch spaceships on Andor or CGI dragons on Game of Thrones and not bat an eyelid, but the sight of the Alligator Lounge, with its torn upholstery and corner pizza oven, makes me think about the Pyramids of Giza and the wonders of which humankind is capable with the right amount of motivation. Nathan may be Canadian, but conceptually, he resides in Synecdoche, New York.

On The Rehearsal, even more than Nathan for You, the choice to populate the episodes with professional and semi-professional actors—and to foreground auditioning, performance, and, especially, scene study and direction at every turn—calls attention to the reality genre, complicating and perpetuating the possibility of an overriding put-on.

For some critics, like The New Yorker’s always perspicacious Richard Brody, who wrote that the first season of The Rehearsal made him want to throw his laptop across the room, Nathan’s instrumentalization of the people around him speaks to cruelty and exploitation: the tactics of a confidence man. And yet, speaking only for myself, the last thing I feel when engaging with Nathan’s work is conned. Rather, I’m fascinated and, more often than not, moved by his thoughtful evocations of solipsism and vulnerability, including and especially his own.

On the one hand, The Rehearsal is a kind of TV funhouse, made up of secret compartments, blind alleys, and escape hatches. On the other hand, it’s a labyrinth that leaves its maker wholly exposed, lost in a maze of his own making with nowhere to hide. There are no safe spaces in his work, in any sense of the word. The agonized desire to be seen, even through a set of meticulous prisms, is at the heart of why civilians sign up for competition shows or panopticonal endurance contests; it’s also what makes Nathan a real artist.

That the Fielder Method is also a dangerous method is part of the joke; it proposes that simple problems demand complex solutions, which in turn become problematic on their own terms. People susceptible to cerebral whiplash are advised to avoid The Rehearsal, and even hardened veterans of cringe comedy may find their worlds rocked. Humour this hallucinatory obliges you to build up a tolerance.

At the end of episode three, an all-time mindfuck entitled “Pilot’s Code,” which finds Nathan trying to get into the mindset of a real pilot (and also contemplating going to therapy), I told my wife that I needed some time alone in a dark room with my thoughts. I relocated to our bedroom and sat there thinking about how to successfully reconcile Nathan’s exploration of nature versus nurture, which begins with a litter of (actually?) cloned puppies being conditioned, Pavlov style, and builds to a larger-than-life recreation of “miracle on the Hudson” hero Captain Chesley Sullenberger III’s childhood, complete with a hairless, nearly naked, diapered Nathan being cradled and breastfed by a puppet mama pumping out milk from her papier-mâché breast.

These scenes are screencap fodder and nightmare fuel (one friend told me she was planning to bring them up in therapy), but they’re also strangely touching. Dangling from wires, Nathan reverses the image of the laptop harness so that he’s the one being babied—the micromanager as his own marionette.

If Nathan is an architect, he’s one whose annotations eventually overwhelm the original blueprint; his genius emerges from how assiduously he scribbles in his own margins. The title of The Rehearsal ’s season-two finale is “My Controls,” a term that refers specifically to aviation protocols but which also draws a bead on Nathan’s world view: his reluctance to cede authority, whether in the cockpit or the editing suite.

In this vein, the image in “My Controls” of that massive plane steadily decelerating after touching down on a far-flung strip of runway in the finale isn’t just a satisfying blockbuster spectacle. It’s well and truly ecstatic, an intricately engineered yet deeply plangent metaphor for a performer whose increasingly kamikaze trajectories belie his ability to stick the landing.

“Did you get enough?” Nathan asks toward the end of “Pretend Daddy,” a question that’s devastating in its particular context, forcing a split-second referendum on whether it’s being directed at another actor, a crew member, or the audience. Or, said another way: has he gone too far? Does acknowledging the collateral damage of the Fielder Method excuse the wreckage left in its wake? For those of us who like our comedy double edged, Nathan’s sharpness is, paradoxically, a balm; he may be a prick or a bleeding heart, but either way, we feel something.

I’m thinking now of the coda of season two’s “Star Potential,” where Nathan reckons with his long-ago stint as a producer on Canadian Idol and wonders whether his experiences rejecting aspiring pop stars left him forever incapable of effectively dishing out criticism and even less equipped to take it. He is finally confronted with empirical evidence of a stranger’s feelings about him—an evaluation rated on a scale of one to ten.

Except it’s not so empirical; he sees a six, looks unhappy, and rotates 180 degrees until it’s a nine. As Nathan flips the slip of paper, we can feel his self-image turning nauseous somersaults along with it. The scene made me think about the possibly apocryphal story of J.M.W. Turner, who was told by a gallerist that one of his canvases had been hung upside down. “Turn her,” the painter replied. Nathan isn’t Turner, but he makes you wonder which end is up. The post Nathan Fielder Lifts Off into a New Reality in The Rehearsal first appeared on The Walrus.

The Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) said Wednesday countries, including India, "leverage" criminal gangs to allegedly conduct "threat activity" on Canadians soil.

June 19, 2025 - 04:00 | Alex Boutilier | Global News - Canada

More than a year-and-a-half after it opened, a site at a the Collins Bay Institution where inmates can inject, snort or swallow substances under medical supervision has only had one user.

June 19, 2025 - 04:00 | | CBC News - Ottawa

Quebec’s public security minister announced changes to how transgender inmates will be incarcerated, citing fairness and safety priorities. The move comes just after the high-profile case of Levana Ballouz, a trans woman who requested a transfer to a women’s prison after being convicted of murdering her partner and kids.

June 19, 2025 - 04:00 | | CBC News - Ottawa

Comments

Be the first to comment