Source Feed: Walrus

Author: Mark Bourrie

Publication Date: June 27, 2025 - 12:10

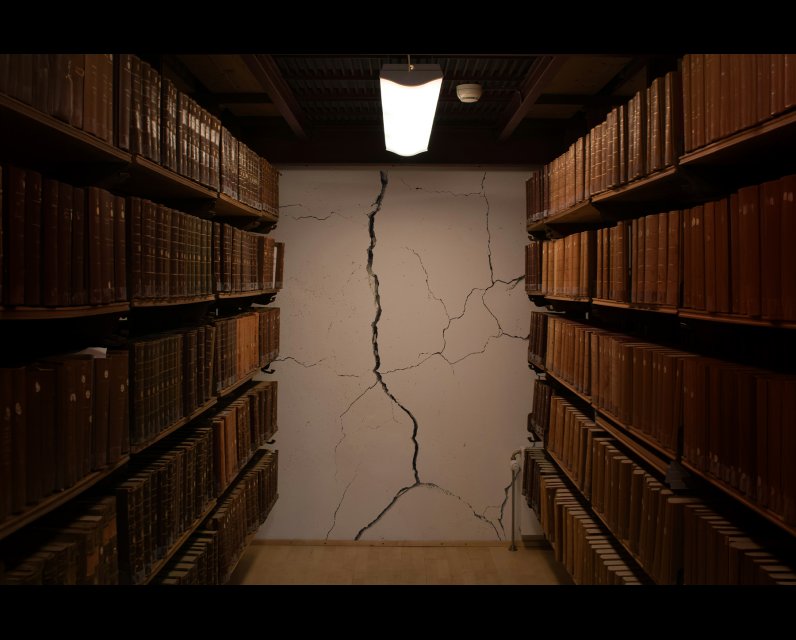

Canada’s Archives Are in Trouble—and So Is Its History

June 27, 2025

R ecently, I showed up in Picton, Ontario, to slake a thirst that I worked up while scouting local quarries for trilobites. I noticed the cute but hobbit-free Shire Hall, the seat of government for Prince Edward County. There’s a building next to it, the local land registry office. These were common in Ontario: little squat fireproof stone buildings that will be there when everything else is gone.

The little registry offices were important to the people who built them. The records of land ownership were stored there, and they looked after them very carefully. If they burned, people could not prove who owned what. Good land records and respect for old documents help keep the peace in our society. Say, you have the old surveyors’ notes of an Ontario township. Then people start arguing about who owns the township’s beach. Did the surveyor draw the property line of the Crown lands down to the water? Or did he draw it to some sort of high-water mark? Do the cottagers own to the water? Or do the cottagers own to the edge of the sand? Can you and I walk along the beach? Those notes can be evidence of who owns billions of dollars’ worth of waterfront.

We should look after all our records that carefully. But we don’t. And we’ve often had bad luck. In 1849, a mob burned down the parliament building in Montreal, along with its library and archives. (A few books and documents were recovered in an archaeological dig in the 2010s, but only enough to remind us of the loss.) Five years later, the replacement parliament building in Quebec burned. The 17,000 books that they’d bought to replace the 23,000 lost in Montreal were all burnt, along with whatever documents were stored there.

After Confederation, some of the country’s oldest records were stashed in a loft in the reading room of the Centre Block on Parliament Hill. That’s where a fire started in 1916 that destroyed the whole building, along with many historic treasures.

This culling of the historic record wasn’t always bad stewardship or poor luck. Few governments have been as careful with documents as the people who run Prince Edward County. During the French Revolution, national records in Paris survived, but regional archives were torched. In 1794, the local government in Puys, along with soldiers and townspeople, burned all the archives and records of the community and then threw medieval statues into the fire to keep it going.

The Palace of Westminster burned in 1834, taking a lot of British history with it. After losing so much, the British started a public records office four years later, beginning the process of putting together its national archives at Kew. The Russians carted off the archives of China’s Qing dynasty in 1902 and didn’t give them back to China until the 1950s. They sacked archives in Germany in 1945, and they’re destroying the historic record of Ukraine now. The Public Record Office in Dublin was destroyed in 1922 during the Irish Civil War when the Four Courts were shelled. Seven centuries of records were lost in a country obsessed with its own history.

Canada got serious about record keeping in the first decades of the twentieth century. Coincidentally, we saw a massive growth in government, generating tons of records and an expectation that the stuff will be kept. And a lot of it is not interesting to people until it is. Indigenous land rights cases are built on written records of Crown agents. And, sometimes, we just want to know the truth about our government: journalist Jim Bronskill fought for years to pry documents out of Library and Archives Canada to find out what Canada’s security agents were doing to New Democratic Party leader Tommy Douglas during the Cold War. (The Supreme Court refused to listen to him.)

If the record is not there and we need it, we’re in trouble, because we probably can’t get it again. It’s also useless if we don’t get to see it because of wonky secrecy and privacy laws.

W e have a crisis in Canadian history just as we’re starting to reassert ourselves as a nation that’s not the United States’ back shed. Not enough students are majoring in Canadian history, and graduate students are scarce.

In 1998, Jack Granatstein wrote a book called Who Killed Canadian History? His less-than-original take: woke people did it. But he was wrong. Culturally, social history and political history are not warring in the bosom of a single state. No one outside academia cares. Canadian researched nonfiction accounts for 5 percent of Canadian book sales. (Canadian authors have just 12 percent of our country’s market, making a joke of the claim that, at least in what we read, we’re not Americans.)

And that’s everything from Fossils of Ontario Part 1: The Trilobites (a book that changed my life) to cookbooks, biographies, and the works of Granatstein. We don’t have a history-textbook business in this country thanks to the Canadian government’s insane copyright rules that allow universities to sell writers’ and publishers’ work to students without compensating rights holders. And it’s almost impossible to promote a Canadian history book. We don’t have the CBC making many Canadian history documentaries. Our newspapers—what’s left of them—don’t have many book pages. People just don’t hear about our books.

Library and Archives Canada, which should be fostering Canada’s history, is part of the problem. A couple of years ago, Robyn Doolittle and a team of the Globe and Mail did a series on access to information and protection of privacy—ATIP—across the whole federal, provincial, and municipal spectrum. “Secret Canada” showed all three levels of government don’t take the public’s right to know seriously. The journalists found, to their surprise, historians were among the angriest users of access-to-information regimes. ATIP was supposed to improve freedom of information, and it ended up as a secrecy tool of bureaucracies, masked as protection of privacy.

A little over a decade ago, when I was doing research for a military safety project, I wanted to see the plans for Second World War fortifications around Prince Rupert, BC. The city was a major shipping point for American forces in the Pacific and was protected by artillery mounted in bunkers. I had a secret clearance. This was a good thing, because Canada’s bureaucracy acts as though Hirohito plays a long game. Those fortifications are long gone, but the plans for them are still secret. I went into a special room to look at the blueprints for the forts that don’t exist, just in case there were spies in the main LAC reading room.

LAC’s secrecy and slowness to declassify records are so bad that people in the military, who have even higher security clearances than I did, pray that their history project involves another NATO partner so they can go through archives in Brussels, Washington, or London to get material.

Charlotte Gray has bird-dogged the history crisis for years. She recently interviewed Stephen Azzi, professor of political management and history at Carleton University, for a long Globe and Mail article about LAC’s ATIP backlog and institutional secrecy. Azzi says he’s been waiting more than two years for records he needs for a book on the 1988 federal election. The discussion in 1988 was about Canada’s relationship with the United States. This is a book that should be written right now, but the author can’t get the material he needs.

Norman Hillmer of Carleton University told Gray, “Today, it is the responsibility of researchers to justify their right to know what governments did or were doing, rather than the responsibility of government to put its records and those of its predecessors into sunlight.”

LAC didn’t make the privacy law. It’s so broad that a simple name and address, no matter how old, is red flagged. The government needs to come up with a more reasonable privacy regime. A person can go to a major library and pull old phone books or city directories to find information protected by Canada’s ATIP law.

There are 200 archivists at LAC working on ATIP. But when a researcher needs help with a project, LAC staff aren’t around. There isn’t money for everything. Historians can trash-talk Library and Archives, but Leslie Weir, the chief librarian and archivist, should not be forced to make so many hard choices. She explained to me that she follows the advice of justice department lawyers. And she doesn’t decide how much money Parliament appropriates to protect and share the historical record.

People in the military pray that their history project involves another NATO partner so they can go through archives in Brussels, Washington, or London.

Patrice Dutil at Toronto Metropolitan University says LAC is Canada’s research facility of last resort. On top of the secrecy, it takes ten days to get a box of records from LAC’s conservation building in Gatineau, Quebec, to the public reading room in downtown Ottawa. It used to take two or three days. (At the British archives in west London, material arrives in an hour or two, since the reading room and storage are in the same building.) Out-of-town researchers can’t afford to spend weeks waiting for LAC deliveries.

LAC is making deals to survive and seem relevant. It has a partnership with ancestry.ca, which generates a lot of clicks on digitized LAC records. Ancestry.ca sells internet access to national records like census results and military records, which are popular with genealogists. Instead of building one large archive with an on-site room for researchers, LAC partnered with the city of Ottawa to share a new building. Ottawa’s sad, brutalist central library will move in with the national archives and the federal library in 2026. The new building won’t have enough room for the national library’s books, so they, like archival documents, will have to be trucked in to waiting readers.

It seems absurd to me that the national library and the national archives are a single entity. They might seem like it to politicians on Parliament Hill or the suits in the Prime Minister’s Office, but they are not the same thing to researchers. They have different mandates: the national library gets and keeps copies of every book published in Canada and maintains a large collection of foreign books. The archives gathers, sorts, and keeps important government and private documents used by historical researchers. The librarians must compete with their library colleagues for the agency’s money. Now the national archives will be part of a city library—in something that’s going to look like an archival Disneyland, with bright sitting areas, and a smudging room, but no historical records and few books from the national collection kept on site.

If we’re going to remain a real country with a serious claim of valuing our culture and history, we need to do better than this. Telling our story well depends on our ability to research it properly, and LAC is often more hindrance than help.

Adapted from a talk given to the Association of Canadian Archivists annual conference on June 12. Reprinted with permission. The post Canada’s Archives Are in Trouble—and So Is Its History first appeared on The Walrus.

For the Ottawa Redblacks to enter their bye week with a much-needed victory in a game on which their season might hinge, they have to prevent the CFL's top receiver from beating them for the second time in eight days. Read More

July 19, 2025 - 17:57 | Don Brennan | Ottawa Citizen

Tyler Heineman hit a two-run home run in the eighth inning and starter Eric Lauer gave up two runs over six to lead the Toronto Blue Jays to a 6-3 victory over the San Francisco Giants on Saturday.

July 19, 2025 - 17:39 | Globalnews Digital | Global News - Ottawa

After a large-scale power outage that left thousands in Ottawa without cooling on July 13, Environment and Climate Change Canada has tips on how to beat the heat if it happens again. Read More

July 19, 2025 - 17:35 | Paula Tran | Ottawa Citizen

Comments

Be the first to comment