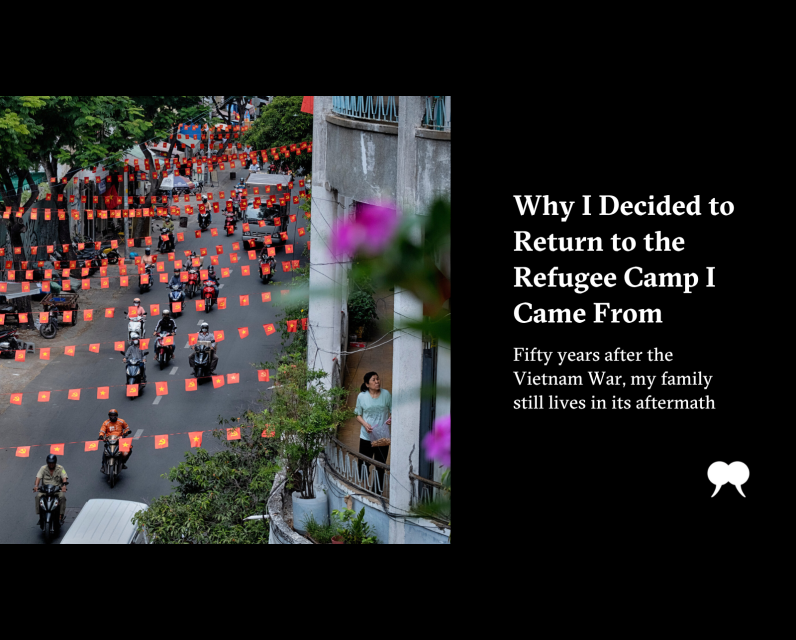

Why I Decided to Return to the Refugee Camp I Came From

I ’m unsure when the idea took hold, but when it did, it wouldn’t let go. Finding the refugee camp again became an obsession, wrapping itself around my consciousness like tendrils reaching for the elusive January light. I would lie in bed at night, my eyes closed, and map out the place in my mind. Our family’s cramped living quarters behind a ditch by the red dirt road next to the soccer field across from the commissary. The large trees with hibiscus flowers blossoming in the sun. The tent where films were projected on hanging canvas. Rusty buses that chartered refugees away to new lives.

When sleep finally overtook me, I would dream of the open sky folding in on itself, children roaming through curtains of monsoon rain, my mother’s slight, electric figure standing in line for rations. Me, a lightning rod, jolting awake. With the glare of the city sneaking in through cracks in the blinds, I sometimes couldn’t tell if I’d made up the past, if the refugee camp in Thailand was ever real.

It had been decades since my mother, my siblings, and I fled postwar Vietnam and arrived at the refugee camps in Thailand, where we were processed by the United Nations and granted asylum. In a black-and-white photograph documenting our first moment as refugees, my mother holds a placard with the number “BT001401.” Her lips are pressed together, sealing tension. Shallow eyes bear exhaustion, like something inside her had been snuffed out.

Clipped to each of our collars is a number from one to five, my mother first, and me, the youngest child, last. No one is smiling, but everyone—except me—is dutifully looking straight into the camera to be captured on film. I am errant, my face turned slightly to the side, eyes downcast. Either I’m a child who can’t follow directions or I’m already on a path away from the narrative given to me, searching for pieces of a broken story.

Every time I look at this photo, I want to reassure this new family that they will be all right, that they are safe. I think of my father, missing from the image, anxious to leave Vietnam and join us at the camp. He was still alive when this photo was taken.

One day, remembering this photo, I googled “Phanat Nikhom,” the camp we stayed in the longest, the final one in a series of camps. The first result I got was a Google Maps location that told me it was in Chonburi province, not far from Bangkok. In its place now were newly built military barracks and a government office surrounded by large patches of brown-and-green fields. I scrutinized the curling shapes of the Thai script and zoomed in on the tops of buildings that looked like tiny Monopoly pieces.

I followed a link to eBay, where someone was selling a T-shirt with an image of a young woman carrying a child on her back. Underneath the image were the words phanatnikom refugee camp—Thailand—1993. I put in a bid but ended up losing to someone else. I wondered who this person was, living a parallel nostalgia to mine.

I downloaded a sixty-four-page master’s thesis by an anthropologist in California and read about identity, community, and resistance inside Phanat Nikhom. When I finished, I thought to myself, “Is this what it was like?” I felt grateful that someone had documented the camp with such scholarly expertise.

I found a technical report on the groundwater supply for the camp and learned the location of wells, the quality of bedrocks, and the amounts of diluvial deposits.

I joined a Facebook group connecting friends who lived in and transited through the area. Late at night, I lurked at posts by strangers looking for people they once knew or reminiscing about a life that’s no longer theirs. I went from one blog to another and saw images of women washing at cisterns, men with their arms around each other, groups of children giving thumbs-up for the camera, rows and rows of tiny makeshift buildings. All this looking fuelled my desperate imagination.

I didn’t tell anyone that the refugee camp had taken over my waking life and animated my dream one. I was afraid my desire would become a broken spell. If I spoke my longing out loud, surely, all traces of the camp would disappear, including my fragmented memories.

O ne evening, after a drunken night out with friends, stumbling from one bar to another, I blurted to my partner—

“I want to go back.”

We were walking home during the early hours of the morning. It was raining that strange horizontal rain, and we had no umbrellas.

“We’re almost home,” he said.

“No, no, I want to go back to the refugee camp in Thailand, return and see—”

“Oh.”

“—what’s there, what parts of myself I left behind.”

We were almost sprinting as we reached the intersection, the traffic lights reflecting on wet pavement. My head was spinning.

“I’m almost forty. I’m scared I don’t know who I am. How I’ve gotten here.”

“Here?”

“This. Toronto. Dreaming in English.”

Either I’m a child who can’t follow directions or I’m already searching for pieces of a broken story.

“Why now?”

“I don’t know. It’s just—”

I sighed.

Everything I was saying felt fanciful and futile at that moment. Nothing about my words, my feelings, or the situation aligned. My life washed away in the falling rain.

My partner held my forearm as we walked side by side in silence, toward the dry shelter of home.

“Okay, I’ll come with you,” he said, with so much conviction at my rash outburst that the possibility of returning to the refugee camp became real for the first time.

V oicing my aching want out loud to my partner made it more bearable, made it exist beyond my inner self. And—just as I thought it would—the desire to return slowly disappeared. As soon as I eased my grip, the idea of the refugee camp slipped away like a stray balloon floating up into grey clouds.

I went back to the progressive routines of my work and social life. Preparing lectures for my classes at the university, where I taught English literature. Joining friends for dinner parties and movie nights. Watching the streetcar go by from a cafe window. Reading a good book in bed next to my partner. I took pleasure from simple housework like vacuuming, taking out the garbage, or washing the dishes.

I flew to Calgary, where my mother lives, to listen to her sing melancholic songs while working in the kitchen. To eat her food and sleep under the same roof as her again.

I took a trip to Mexico City in late summer and marvelled at the vibrancy of a place that reminded me so much of Ho Chi Minh City, where I was born. If my partner had asked me then—the both of us standing in the wide expanse of the Zócalo square—if I still wanted to find the refugee camp, I would have turned to him and said, What camp? What are you talking about?

I’m often ruminating on the past, staring down the long tunnel of memory. When this happens, the more I try to resist, the more the past grips me by the ankles, and then I fall backward, hands and feet flailing in the air. But thinking about this particular moment in time—the summer of 2019, a moment before things changed—I now see that I can be swept away by the present too, that it’s easy to be pulled along from one day to the next, further and further away from the past.

W hat started it all—again—was death.

What made the present, as it was then, unlivable was the untimely death of my best friend and mentor, Don.

Don had a way of pulling you into his confidence, taking you by the arm and whispering something only the two of you would get. I first met him when I enrolled in a graduate program at a Southwestern Ontario university, where he’d been an English professor for decades. A white immigrant to Canada from Trinidad, Don had that singsong island accent, which mismatched the looks he inherited from his German ancestors. He started his career as a Romanticist, writing a book on the English poet John Keats, but gradually began research on Asian North American literatures. He was one of the few scholars in Canada doing this work, and he’d agreed to supervise my thesis.

During our first meeting in his bright corner office, he’d asked if my family knew I was gay. His question came out of nowhere, shocking me as I rambled on about research topics and book titles. But this was Don—bold and curious, awkward and up close. I didn’t realize it then, but thinking back, I understand it must’ve been his own unspoken queer sexuality that was on his mind. He must’ve been wondering how someone decides to come out to their family.

Once, we had lunch, and he was characteristically charming. He folded up his tiny glasses before fitting them inside a small tube, then dug his knuckles into his eyes. After a quiet sigh, he hunched his shoulders and started rubbing his upper leg vigorously with both hands. He took long, silent pauses in between sentences. “You’re lucky that your generation can be gay so openly—” he began.

After he came out, at the age of fifty, we went dancing and vacationed with our partners. We told each other secrets, asked for dating advice, and checked out cute guys together. He drove me to Ikea when I needed bookshelves and had me over for Christmas dinners with his children. There was a twenty-nine-year age gap between us, and despite our tropical backgrounds and different life journeys, we’d found each other in the snowy landscape of Canada. Don was a soulmate, the closest thing I had to a father figure.

When I received the phone call from his partner telling me that Don had had an aneurysm, it was an unusually warm October afternoon. I saw the caller’s name on the screen first, and the moment I picked up, I knew something was wrong: Don had had a pounding headache, he’d pushed through and lectured, he’d driven home, he’d made dinner, he’d collapsed into a seizure, he’d been taken to hospital, his head full of blood.

I started shaking—the sensation of being pierced by an icicle.

I asked if I could see him, but it was too late. The doctors were going to operate on his body in a few hours: cut him open, remove his organs—and put them into someone else.

When I saw him next, his ashes were sealed inside an urn. I held it in my hands. It was heavy.

A nd then something else happened. In the midst of my grief—that throbbing deprivation that rearranges the mourner’s body—another lurking death resurfaced.

Don’s passing pricked at the open wounds of my past. It set off something I knew—indeed feared with every fibre of my being—was long overdue. For almost three decades, I’d managed to avoid coming to grips with my father’s mysterious death while seeking asylum.

In 1989, my father packed his belongings and followed the same route that we, his family, took to get to the refugee camps in Thailand. Like so many refugees before and after him, my father lost his life in the open waters. His death had always been a fact of my life, but I’d never actually mourned him—never looked his death directly in the face and said, Here, I am here.

For years, I had made various mental negotiations with myself: I’ll deal with his death when I’m in a better place, when I’m more stable, more secure, more mature. Perhaps if I just sidestep it at every opportunity, it might somehow go away on its own. If I delay it enough, working through his death will become a problem for the future.

But the future always arrives, sooner than anticipated and without warning. Attempting to mourn Don felt doubly hard because every feeling, every thought, every question opened up to more feelings, more thoughts, and more questions about my father and about the nature of death itself. Everything became entangled because both men left my life with the same abruptness—a boxer’s illegal knock to the back of the head.

One moment they were in the world, and the next they were gone. I didn’t have the chance to say goodbye or the gift of time to negotiate and pray, to imagine how I might reorient myself without them—only concussive questions and nowhere to turn.

I lost my father when I was a child, and with Don’s passing, I experienced that loss again as an adult. One death became two, and the two are now one.

My father’s death had always been a fact of my life, but I’d never looked his death directly in the face and said, Here, I am here.

O ne cold and windy afternoon, an image shoved its way to the front of my mind: a block of ice sitting inside a round plastic basin.

The ice is slowly melting in the heat of the room, with mosquito nets hanging from the ceiling. Slippers are strewn one on top of another in the entryway. My mother, lying on her side, fans me into afternoon slumber, an elbow propping her up. A sliver of light cuts across our reclined bodies.

In the refugee camp, ice was a luxury. Ice was the gold we bought from nearby locals through an opening in the fence. I’m reminded that the border of the camp was not impermeable. Goods and things and people passed through gaps in the corrugated tin and barbed wire barriers, places where guards accepted a few surreptitious notes passed into their waiting palms.

Thinking about what happened to my father led me back to thinking about the camp, about how he never arrived. If it was possible to enter and leave that enclosure, then why couldn’t my father? Why him? Why this outcome and not another?

I imagine him, in the middle of the night, lifting the corner of a fence and squeezing his head through first. I imagine him walking with light steps to where we are sleeping. I imagine him parting the mosquito net, then sliding his tired body next to our resting ones. I imagine the sound of crickets. The brilliant orange sunrise.

And so the refugee camp took up residence in my mind again. I began to make serious plans to return, looking into flights, accommodations, and, most importantly, the precise location of Phanat Nikhom.

My partner encouraged me, suggesting that we go the next summer, that we also travel throughout Southeast Asia. Go back to Vietnam, where I, at that point, hadn’t been for over a decade.

The trip to find the refugee camp in Thailand became an entire journey, one that would carry the weight of my missing father, my refugee past, and my ability to continue living in the present. It took on a mythic quality—the magical act that would propel me forward.

But because the cosmos has its own plans and cares nothing about our human need, the entire world shut down in early 2020. For months, a virus had been replicating itself inside human cells, moving from body to body, making the infected sick with severe flu-like symptoms. Circulating in the air, the virus travelled fast and far, reaching every corner of the globe in a matter of weeks. Deaths began to multiply at a dizzying pace.

I folded back into myself, feeling the insignificance of my own experience. Minimizing my own sorrow. Denying that leaden feeling in my chest.

But I’ve had to learn the hard way that it doesn’t work to pit a personal experience, so embodied and immediate, against a social one, so grand and urgent. There has to be room for both, because the personal is the training ground for the social, and the social gives form to the personal. I had to figure out a way to make enough space for what I was going through if I was to be good or useful to anyone else besides myself, if I was to stay tethered to this life.

That was when, one evening, in a hazy confluence of illnesses—stomach pains, allergies, headaches, and skin rashes—I opened a blank document on my computer and started sketching with words an image of a man falling through empty space.

It took days for me to recognize that this man was my father, and that my task was to populate that space he was falling through with my own memories and desires, and in doing so, to make his fall from this life acquire some significance beyond another senseless refugee death, a nameless person disappearing from history.

It was a way, also, of saving myself.

I began to move, even though airplanes were grounded and national borders were shut. I travelled long distances across the years in my mind. I went to places overgrown with weeds and tangled roots, places that required hard-to-obtain entry visas.

I asked myself for permission.

My task was to make his fall from this life acquire some significance beyond another senseless refugee death.

Returns aren’t just physical, I realized. They’re also psychic and emotional. The past, the refugee camp, and my father had always been there waiting for me, if I dared to go further down that memory tunnel, to extend my fingers a little more and touch, with the tips, something like the truth.

I was chasing certainty.

I had become, at the core, simply a fatherless person looking for answers. But when I turned my gaze backward, the first things I saw were bomb craters littering the landscape. Unexploded ordnances. Unmarked graves. Remnants of war.

I needed to revisit the Vietnam War—where my father fought and where my mother, my siblings, and I still live in its ongoing aftermath. The war ended before my birth, but its fighting shaped my life in ways I have yet to realize. To arrive at a personal resolution, I would have to trek through the ruins of many demolished lives.

Those who have been through war know that war scrambles our stories and timelines. Our fragile worlds. It leaves behind no continuity, no whole. Its legacy is mess.

To make sense of what happened to my father and to my family, I would need to bend memory, stretch facts, and conjure desire. Lay out all the contradictions.

I had to unstitch myself to make a story.

So I fell into the past, grasping for some kind of coherence.

It felt like trying to hold on to the falling rain.

Adapted and excerpted, with permission, from The Migrant Rain Falls in Reverse: A Memoir by Vinh Nguyen, published by HarperCollins Canada, 2025.

The post Why I Decided to Return to the Refugee Camp I Came From first appeared on The Walrus.

Comments

Be the first to comment