Whiteouts, Ice Roads, and Wolverines: What Working at a Diamond Mine in the Far North Is Like

D escending into Diavik is like landing on a distant moon, the world sealed in a hard sheet of ice and snow stretching in every direction. The plane circled a few times and then slid into a landing pattern which brought it into contact with a rough strip that shook the outdated Canadian North Boeing 737, one of the few larger planes that can touch down on gravel.

The cold that ripped through the plane after the door was opened caused a wave of grumbling. The cabin speakers came on and the pilot welcomed us, casually noting that the temperature outside hovered around thirty below. This was why we had to fly with our boots and parkas in hand. I had seen men in fleece zip-ups and sneakers turned away at the boarding gate.

The second shock as you left the plane, after the freezing wind pulled your breath straight out of your chest, was catching sight of what looked like a 1970s Canadian school bus. It was our transport to the intake facility. Steamed-over windows, tattered green seats, and rubber floor mat: it was all exactly as I remembered from childhood. I was not a tall man, so having my knees bashing into the seatback ahead of me was a novelty, and I felt for the bigger gents whom I could hear complaining, and who must have been sitting sideways.

We crossed the length of the island, passing what looked like a natural hill but was actually a massive stockpile of excavated material from the mine. The twenty-minute ride to the main camp ended at a huge blue and white steel building. We were directed through the front doors, into what looked like a food court in a large mall, and lined up behind a checkpoint, happy to be in the warmth. We each walked through a metal detector, and our bags were put through an X-ray machine. It was very much like airport screening, except we could all smell the food being cooked in the huge kitchen across the eating area. Most of us had been travelling for at least a full day, flying in from all over the country, so we were hungry.

After going through intake, you were handed a room assignment. Mine was in the building we were standing in—near hotel-quality accommodations, by camp standards. Others weren’t so lucky. Their assignment meant a long walk down an endless hallway, then a brief step back into the cold to cross the road to the contractor’s camp—a smaller, harsher setup more typical of mining camps across Canada. Tiny bunk rooms, narrow beds, heat cranked to sweat-inducing levels. I’d spent months there before, and I didn’t take for granted the upgrade my construction management role now afforded me. After years of dragging my aching body through one brutal site after another, I figured I’d earned it.

I walked out onto the edge of the tailings impoundment. It lay on outcrops poking out from the ice-covered surface of a lake. Diavik Diamond Mine sits on an island in Lac de Gras, north of Great Slave Lake and Yellowknife, in a frozen expanse just 220 kilometres shy of the Arctic Circle—a technicality, really, since the cold here rivals the North Pole on any day. As far as I knew, the plant site building was the largest structure in the entire territory.

The region was a maze of water and stone, making any attempt at building infrastructure, be it a mine or human settlements, challenging and costly. The rock beneath us was among the oldest in the world and was the very reason the mine existed. It was kimberlite, a rare, dark igneous stone known as the primary host for diamonds. The gems lay hidden inside it, needing no chemical extraction—just crushing, rinsing with water and ferrosilicon, then spinning through a cyclone where diamonds and waste rock split apart by difference in density.

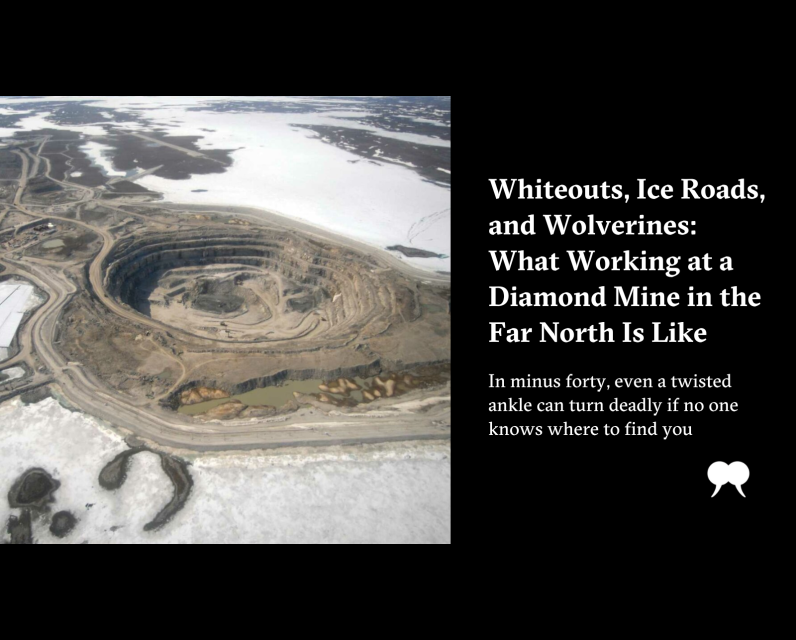

To reach this treasure, the land itself had to be reshaped. From the air, the mine appears as two vast open pits. Known as A-154 and A-418, they were gouged out over years under the watch of an army of engineers. Their terraced walls, called benches, spiral downward in geometric precision, like an inverted ziggurat. Along these narrow ledges, giant Komatsu haul trucks inch up and down. At the bottom, far below the former lakebed, massive electric shovels claw out kimberlite and ancient rock.

Our duties covered the entire operation, monitoring several projects at once. It was our job to assure things were being done to design, and when changes were needed, that those changes were met with the intent of what was required.

The gems lay hidden inside, needing no chemical extraction.

The North provided more than its share of dangers, the first of these being the cold. Improperly dressed, forty below zero will kill a man in about thirty minutes; he is likely past the point of rescue after fifteen. Hypothermia and severe frostbite are an excellent tag team for death. Wind ups those risks substantially, dropping the actual temperature well past what a thermometer may tell you and adding to the air conduction of body heat.

One of the biggest hazards was whiteout—near zero or total loss of visibility caused by wind-whipped snow, turning the landscape into a blinding void. In a place where 300-ton haul trucks roamed, that kind of blindness wasn’t just disorienting; it was deadly. The mine dedicated days to training, much of it focused on staying safe around heavy equipment. From the cab of one of those towering trucks, the scale and danger became clear: a vehicle the size of a shipping container could be parked directly in front of you and still disappear from view. Operators spent weeks in simulators and trained closely with experienced drivers before being allowed to operate solo. Even then, accidents happened. Fatigue, distraction, or a moment of confusion could prove fatal when you were behind the controls of something that massive.

But the threat wasn’t limited to giants of the fleet. Even a simple pick-up had to be ready for the worst. A hard-and-fast rule was to never drop below half a tank of fuel. If you were caught in a whiteout and had to pull aside for a few hours, or longer, how else were you going to stay warm? Our pick-ups were stocked with emergency supplies: food, blankets, shovels, fire extinguishers, med kits. As a manager, nothing was more stressful than knowing someone on your team was stranded in a storm and there was no way to reach them; the very conditions that trapped them made rescue impossible.

Weather forecasts were monitored constantly, a fixture in our daily safety briefings, along with strict tracking of each person’s movements. Radio check-ins were mandatory any time someone changed locations or stepped out of a vehicle. When possible, the buddy system was enforced—because in minus forty, even something as simple as a twisted ankle could turn deadly if no one knew where to find you.

For newcomers, the rules could feel overwhelming. But most adapted fast or didn’t stick around. Every project attracted people who thought life on site sounded exciting, only to realize it demanded more grit than they had bargained for.

Wildlife encounters were a routine part of life in the North, and foxes were by far the boldest. One day, while driving around the site, I spotted one: a vivid red shape trailing Wayne, one of our lead surveyors. Wayne was out marking the route for a new dam, seemingly unfazed by his four-legged shadow. Foxes had a habit of tailing surveyors, drawn by the movement or maybe the company, but they carried a high risk of rabies and could turn aggressive without warning. Wayne had fended off more than a few over the years—his stories kept us laughing around the dinner table.

A day later, I was at the dam. The sky was clouded in, but we were not near whiteout yet. Beside me was Jay, my cross shift, the guy who filled my role when I was rotated home. I was watching another haul truck roll into view, appearing like a ghost out of the drifts, when Jay bumped my arm.

“You see it?” he said.

“What, fox?” I asked.

“Nah, goddamn, look at that beauty,” he said.

Then I saw it. Huffing and puffing its way along the dam surface, tossing snow to either side as it shuffled. A wolverine in the wild was something I never fully adjusted to; they were part wonder and part nightmare. Provoked, they are like a mini grizzly high on meth. The wolverine came straight for our truck, and I was glad for the 3,000 kilograms of steel, rubber, and glass between us. He cruised past, and with my window down just a touch, I could hear the rasp of his breathing. He gave us the slightest side-eye, just a passing glare. His tracks, left in perfect suspension in the fresh flakes, were already disappearing.

O ne day, touring the island in the narrow band of sunlight we had in the winter months, we saw other lights. They belonged to long-haul truckers who had driven the ice road from Yellowknife, crossing over 400 kilometres of frozen lake and the occasional patch of ground. The ice road was the one shot the mines had at getting what they needed—fuel, food, gear—before the thaw claimed the route. Miss the window and your only option was to fly it in, at insane cost and with all the headaches that came with it.

Diavik’s airstrip averaged two Hercules flights a day, its schedule in constant negotiation with other mines and remote communities that depended on the same fragile network. Coordinating the logistics of it all was like running a troop movement, with supply lines dictating not just the pace of work but how much ore could be blasted and hauled out. Maybe that’s why so many who took these jobs were ex-military.

The lights grew brighter and sharpened into shapes: long trailers, flatbeds stacked with wooden crates, rolls of liner, and fuel drums. One flatbed carried the blade from a dozer, and on the next, the dozer’s engine and cockpit. These huge machines were sectioned off and shipped around the world to buyers who rebuilt them on site. The process took weeks. Every day, when you drove by the yard, you would see more pieces of the puzzle fitting together, cranes lifting parts into place and flashes from the welders who connected them.

The convoy rumbled up the ramp onto the island. Trucks blew their horns as they came ashore, undercarriages crusted with frozen sludge and gravel, windshields smeared with weeks of grime. We blasted our horn in response. Headlights still stretched out for kilometres across the ice, and it was half an hour before the final vehicle pulled in. Then the radio crackled to life: “Last truck off the ice.”

Diavik was one of three mines the ice road fed: Snap Lake and Ekati being the others. I expected that, as the sun fell, there were still trucks out there, pushing through the last stretch toward those distant outposts. Not everyone made it. One year, a dozer fell through the ice, taking the operator to the clear lake bottom. Men I spoke to said the radio call had been awful, a man yelling, then weeping from the cab of his truck. As the dozer plunged below the surface, fragments of crust rose and then settled, water pouring out over the gap where the machine had been.

Drivers speak about the way the road shifts beneath them. Speeds are tightly controlled, and progress can be agonizingly slow—any faster and the pressure might fracture the sheet below. Sometimes it feels like the road lifts to meet you, released from the load of the trucks just ahead. Then come the white-knuckle moments. Engines fail. Visibility drops until all you can see are two faint running lights in the distance. Wind slams into box trailers, threatening to tip them. All the while, there’s that awful soundtrack: steel frames groaning under strain, ice creaking and popping beneath the wheels. Some men and women drive the road every season, returning like sailors to the sea; others travel it once, drawn by the adventure and wages, retreat to Yellowknife, and quit on the spot.

T he morning was clear. I had already knocked out three meetings and done a full sweep of the site. Projects were moving, and with two days left before heading home, I was winding down. But I had a treat lined up first. Sitting in my truck, sipping piping hot coffee, I watched a helicopter warming on the tarmac. The pilot was doing a run-through, getting everything checked and making sure nothing important had seized overnight. The Airbus AS350 B2 had come to life without so much as a whine, and the sound of its engines was confidence building. The helo was a thing of beauty, the red and white livery glittering in the sun.

There was a knock on my window, and a young woman jumped in. Aanya was a geologist with the mine. An Indian woman who had grown up in Brantford, outside of Hamilton. She was one of those people who pored over rock like a librarian pores over ancient texts. Her dedication and joy were contagious.

“Good morning!” she said, cheering my coffee mug with hers. “Can you believe we get to do this today?” I smiled at her. Enthusiasm was a trait I held in very high regard when staffing a project. Mike, the pilot, hopped out of the cockpit.

“Okay, I think we are on,” I said. I switched off the truck and got our bags.

We stood off the pad until Mike waved us in. The engine was running, but the rotors were not engaged. He sat us down and got me set up with the five-point belt in the back seat. He then shut my door. Aanya sat up front, dazzled by the instrument array with its mix of digital and analogue dials and switches. When he jumped into the cockpit, Mike signalled us to put on our headsets.

“Good morning, flyers. Welcome to Diavik Airways. There will be no meal on today’s flight,” he said. Mike ran through a very brief repeat of the safety walk-through we had done in the office that morning—namely, that in the event of an “unscheduled touchdown,” we were not to exit the aircraft until the rotors had come to a complete stop. The ice now was very thick around the island, so nothing would be considered a water landing if we did go down. We were in full weather gear, but the helo was warm and loud.

Mike started up the rotors and announced to flight control that we were lifting off. Diavik tower told us we had a clean sky, with no incoming or outgoing aircraft and no blasts planned. Blast operations occurred at intervals around the site, and activities would be suspended during these detonations. Using explosives to break apart the earth has been a staple of construction for centuries. Things got a lot safer after Alfred Nobel brought stable, reliable charges to market. But even now, there’s no way to fully predict how the ground will behave. Distance is still the best defence. Blasting, however, was new to a lot of pilots. I saw more than one get fired for trying to give clients a front-row view. Flying rock, shockwaves, and light aircraft are a dangerous mix.

We were up, snow and ice spraying as we pulled away. Mike didn’t waste a second. He dropped us low and punched it forward. The world opened around us—wide stretches of frozen land, endless sky, and sunlight. It felt like a controlled free fall across the top of nowhere. Aanya laughed into her mic. We both felt it: pure joy.

Mike took us for a spin over the mine: the huge buildings, the main camp, the deep open pits with their frost-coated walls and benches reaching down into the earth.

We could see haul trucks climbing out of the pits, inching along the roads that wound round the edges, steam rising off giant electric shovels, shadows where the sun had not yet reached. The wind buffered the helo, shaking us in our sharp turn.

“Okay,” Mike announced, “let’s go see some drilling.”

He straightened out and sped toward a point in the distance. The landscape was so featureless, it was hard to judge our altitude. We were well above the treeline, but even then, I couldn’t tell if I was looking at a scattering of boulders or the crest of a ridge. Then a small dot appeared below, trailing a smooth line behind it—a snowmobile cutting across the frozen surface. It gave me a sense of scale, if only for a moment.

He banked hard left and right, the horizon tilting and snapping back, the exhilaration of it all fully framed in our wide eyes.

Looking out over the hard white expanse, I was reminded of the Dene legend about the seasons. The world was locked in endless winter. One day, while hunting, the first people came across a bear with a sack around its neck. Asked what was in the sack, the bear said it was the abundance of summer. They could not convince the bear to hand over the sack, so they went back to their village and planned a feast for him, thinking they could get him to sleep and then steal the sack. But when he appeared for the feast, he wore no sack. Frustrated, the first people followed him home. While he slept in his cave, they found the sack guarded by two other bears. A battle ensued, and although three hunters were killed, the fourth hunter, mortally wounded, was able to tear open the sack. Sunlight and warmth burst forth onto the world and covered the land, trees grew, and strange birds filled the sky. From that day on, summer came to the Dene every year.

The legend seemed to echo some ancestral recollection of the last ice age, carried forward in oral histories. Now, another shift in climate was underway. I thought of this flat, windswept plateau, sparkling with the hardest substance on earth, and how the ice road lasted for fewer and fewer weeks every year, and how all this could soon become a memory, passed down through generations.

We began our descent, and I could see the drilling camp—a drill rig on the ice surrounded by containers and two large tents. We circled once and then descended where orange paint marked our landing zone. Mike judged the wind direction from his instruments and the flags posted around the camp. We settled down without so much as a bump.

In the drill tent, the crew were boxing and logging rock core. The drill was spinning through the ice, grinding into the layers below. The noise required hearing protection. I noted the well-marked “kill switches,” in case of emergency. No fewer than three fire extinguishers were visible. The driller gave us a quick rundown of the borehole, its location, and the depth they had reached, about thirty metres below the lakebed. They were chasing deposits of kimberlite that could yield more diamonds and extend the mine’s operational life. I took notes on the progress of the drilling and any issues they had run up against—stuck casings and a blown hydraulic line. Both were the bane of working in extreme cold. I’d seen heavy-duty steel buckets, as big as refrigerators, snap like porcelain in fifty below.

Eventually, we returned to the helicopter. Mike had been watching the weather. Rough stuff was coming in, but we should be clear to get back. We lifted off in a burst of powder, and soon he was back to carving through the air. It was all speed, noise, and motion—an adrenaline shot straight to the chest. Our camp emerged as a dark spot from the sky, black roads and piles reflecting against incoming cloud cover. Halfway there, Mike gave us a taste of wild flying. He banked hard left and right, the horizon tilting and snapping back, the exhilaration of it all fully framed in our wide eyes.

It was snowing as we landed. I helped Mike tie down the helicopter and cover it for the night. The setting sun crushed the horizon into fragments of red and orange bleeding onto white.

Two weeks after I left the site, I heard something had slunk under the kitchen in the contractor camp and had been chewing away at wires and hoses, causing havoc with the systems and the electricity. Unsure how to deal with the situation, they sent in Charlie, a big Dene chef who also happened to be a skilled hunter, trapper, and hockey goalie. Suited up in full goalie gear and tied to a rope, he dropped beneath the floor to see if he could reach the animal. Onlookers cheered as Charlie was pulled out, screaming. In his hands was the culprit, still thrashing, having already clawed clean through his padding: a raging wolverine.

Excerpted, with permission, from This Rare Earth: Building the Dams, Mines and Megaprojects That Run Our World by Jeremy Thomas Gilmer, published by Véhicule Press, 2025.

The post Whiteouts, Ice Roads, and Wolverines: What Working at a Diamond Mine in the Far North Is Like first appeared on The Walrus.

Comments

Be the first to comment