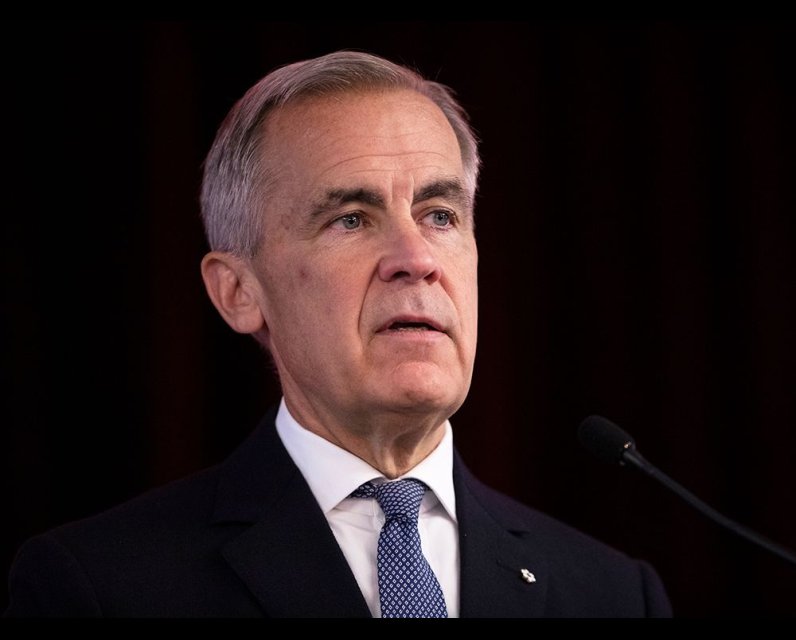

What Mark Carney is missing, according to this eminence grise insider

Fen Hampson is a serious man; he thinks for a living. A marquee player in Canada’s foreign policy brain trust, he isn’t frivolous. His opinions are measured and deliberate.

As director of Carleton University’s Norman Paterson School of International Affairs in Ottawa — and now Chancellor’s Professor — he’s shaped generations of Canadian policymakers and diplomats. Today, he leads the World Refugee and Migration Council as president; co-chairs the Expert Group on Canada-U.S. Relations, together with Perrin Beatty; and weighs in on a range of prickly policy issues, including cybersecurity, migration and the Arctic.

It’s the latter topic that has my attention. What does Fen think of the two ambitious nation-building projects being assessed by Prime Minister Mark Carney’s government to reboot investment, infrastructure and security in Canada’s vast Arctic? Northern Canada, specifically the three territories (Nunavut, Northwest Territories, and Yukon), accounts for about 40 per cent of Canada’s landmass and roughly 0.5 per cent of our country’s GDP.

The first project, dubbed the Port of Churchill Plus, contemplates a massive upgrade to the Port of Churchill and related infrastructure, including the construction of an all-weather road and upgraded rail line over muskeg, a new energy corridor, and marine ice-breaking capacity. The second, the Arctic Economic and Security Corridor, is pitched as an all-weather, land-based, and port-to-port infrastructure network connecting the Canadian Prairies through the Northwest Territories to a deepwater port at Grays Bay, Nunavut.

“I think one of the challenges that Mark Carney faces is really, to articulate a strategic imperative for doing what is increasingly a growing laundry list of commitments,” Fen says. “Canadians tend to look southwards; they don’t look northwards,” he adds. “Most have never been to the Arctic.

“Some of the initiatives you point to,” Fen continues, “which are still, shall we say, prime ministerial pipe dreams, I think, are important to be realized.” And Carney himself, growing up as a young kid in a Northern community, “obviously doesn’t need any persuading about the importance of the Arctic,” Fen observes. Carney’s challenge is to persuade Canadians.

Like Carney, Fen is one of those rare individuals who has spent time in the North. And it’s his experience in Rankin Inlet, an Inuit hamlet in Nunavut — as a teenager, working on a geophysical survey for a mining company — that anchors his thinking about the Arctic.

In 1970, Fen was hired to conduct surveys after a vein that had been mined for six years ran out and the mine was shut down. “You had all these people who’d been working in it, who were suddenly out of a job,” Fen recalls. “We’re seeing that now,” he adds, “with some of the diamond mines in the North.”

Fen’s advice to Carney’s government? Do your homework, do the number-crunching, and make sure you understand the business case. “Ottawa — and it’s not just Ottawa, it’s the provinces — need to take a very hard look at what’s the business case here, what kinds of resource development are we talking about,” Fen advises, to ensure these projects will be sustainable.

“Is it going to be a state-led enterprise,” Fen also asks, “where Ottawa doesn’t just write the cheques?” Is the government proposing to do what it’s doing on the housing front — the actual building itself — because there’s no private sector willingness or appetite to do it? The challenges could be daunting, he says, “because you have all the problems, pitfalls, pathologies of a government.

“You know,” he adds, “the Chinese would be more than willing to write big cheques, but I don’t think we necessarily want to go there. So who are your investors going to be? And that requires, I think, a very different kind of relationship between government and the business community than we’ve had for the past 10 years.”

“So, how is Carney going to convince Canadians to prioritize investment in the Arctic?” I ask — restating our conversation’s overarching theme — especially after a decade of government inertia in the North and austerity budgets in our immediate future. Getting Canadians to turn North, Fen concurs, is going to require a compelling narrative from the prime minister and his officials.

The risks in the Arctic have changed, Fen explains. “Russia’s Arctic militarization,” he says, “now coupled with China’s near Arctic state ambitions … have made the entire region a strategic threat.” The two countries see the Arctic as central to their security, their commerce, resource development, and they’re investing billions, particularly the Russians, in icebreakers, airfields, critical mineral extraction and transportation corridors.

America’s “Manifest Destiny Redux” — Fen’s way of describing U.S. President Donald Trump’s provocation — is also relevant to a Canadian population, 90 per cent of whom live within 100 miles of the Canada-U.S. border. Our country has little strategic depth, Fen warns; that’s a military term meaning the distance between a country’s front-line boundary and its population centres.

More positively, Fen is of the view that Ottawa, on the diplomatic front, “is obviously putting the pedal to the metal to engage with the Nordic countries in a variety of ways, whether it’s building icebreakers, closer defence cooperation training … through the NATO framework, the appointment of an Arctic ambassador, consulates in Alaska and Greenland.”

The first tranche of nation-building projects, endorsed by Carney’s government this month, Fen suggests, are designed to build momentum. “That first list,” he says, “is really to show that the government can actually do something, and deliver in a fairly short period.”

For the North, he says, it’s going to take “a bold visionary — someone like C.D. Howe — who can break through the bureaucratic inertia to actually knock heads and build what the moment demands.”

“That’s how we got a St. Lawrence Seaway; it’s how we got a TransCanada pipeline,” he asserts. “We don’t need another task force, we need a builder or builders, a C.D. Howe for the 21st century North. Because at the end of the day, you can have the best plan, but unless you have someone who can actually execute it, and knock heads, and be unpopular, it ain’t gonna happen.

“I think we’re still a bit blasé about what’s happening in the country,” Fen observes, pointing to worrisome employment and GDP stats. “I know Mark Carney gets it,” he adds, “because he rarely smiles and he looks like a worried man.”

It may be time for Carney to start giving weekly fireside chats to the Canadian people, Fen suggests, “to build that relationship, to really say, you know, we’ve got to come together, otherwise, we’re not going to be a country.

“He’s got good executive management skills, he’s a hard worker, he’s highly disciplined, he goes on 26-kilometre runs, whatever, but his M.O. is still quite secretive,” Fen reflects. “Being that central banker, you don’t announce the interest rates until you’ve decided on the interest rates,” he adds with a smile, “and I think that’s where he really has to change his tune.

“You know, Canadians trust him. That’s important,” says Fen. “They take him seriously. But he now has to level with Canadians, and say, ‘I can’t solve everything for you. And if we’re going to rebuild this country and make our economy resilient, you’re going to have to give up things.’

“You’re going to have to work harder and you’re going to be poorer.”

That’s a hard message for a politician to deliver, Fen says.

Our website is the place for the latest breaking news, exclusive scoops, longreads and provocative commentary. Please bookmark nationalpost.com and sign up for our newsletters here.

Comments

Be the first to comment