How Canada's short-term thinking sparked a national housing crisis

OTTAWA — At just 32, Eddie has a six-figure salary from a major financial institution, stocks, and no debt, including his rental property that nets him more than $5,000 a month. He lives frugally and invests as much as he can.

Eddie wants to buy a house in Ottawa, as close as possible to his downtown job, and is willing to spend up to about $900,000.

His wish list seems pretty basic: a decent neighbourhood, a back yard, and at least three bedrooms to accommodate what he hopes will one day be a growing family.

And yet, Eddie has been searching for more than seven months and still can’t find a match.

“It’s been an eye-opening experience,” said Eddie, who asked that his last name not be published.

Eddie’s frustration is far from unique. Canadians in countless communities — especially urban areas, where most live — have in recent years been finding it extremely difficult to find the homes they want at prices that seem reasonable. For some, like Eddie, the housing crisis has meant staring down a market where prospective buyers are looking at paying what they widely consider to be too much for too little. For others, whose finances aren’t as strong, the situation is more dire: it means raising a family in an overpriced, cramped apartment and long commutes to work.

Economists and other analysts say the root of the problem is largely a lack of supply that can be traced to rising taxes and other input costs, zoning chokeholds, and a tangled web of multi-jurisdictional bureaucracy.

But for something as socially important as housing, not to mention a key driver of both the economy and job creation, how did we end up here?

In the wake of the federal government’s unveiling last week of a major new housing program, National Post is taking an in-depth look at why Canada has a housing shortage that has in recent years led to a range of problems, from rising home prices to homelessness.

Analysts and industry officials say much of the problem can be traced back to government, with taxes now comprising the largest cost in the price of a new home.

All three levels of government, each of which plays a role in the convoluted home-building process and takes a significant cut along the way, say they recognize that Canada needs more homes. And while each says they’re taking steps to make that happen, housing industry executives and economists say there’s a long, long road ahead.

Phil Soper, chief executive officer of Royal LePage, said Canada has been underinvesting in infrastructure and housing for at least 30 years and that it will take time to fix the problems. A concerted effort over the next four or so years could at least begin to turn things around, he said.

“It’s not going to happen overnight.”

On Sept. 14, the federal government, which is responsible for national housing strategies, signing cheques to provincial non-profits and Indigenous housing, unveiled Build Canada Homes . The $13-billion program is intended to help more homes get built more quickly, especially less costly homes for middle- and lower-income Canadians.

Prime Minister Mark Carney said the program will reduce the upfront building costs by providing flexible financial incentives to attract private investment and trigger larger projects. The new organization would also use federal land in six cities for the construction of 4,000 factory-built homes. It’s part of an effort to more than double the current pace of housing growth to 500,000 a year for the next decade.

Some analysts and industry executives salute the new program, but question how much effect it will have, especially in the short term. “Creating yet another federal entity does not seem a good use of resources,” the Canadian Home Builders’ Association wrote last month in its pre-budget consultation document.

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre said bureaucracy is part of the problem in the housing crisis and Ottawa just added more of it.

Ottawa has also taken steps to try to limit demand for housing by cutting immigration and foreign student numbers, while trying to make housing more affordable by eliminating the GST for first-time homebuyers who purchase homes valued at less than $1 million.

Provinces and territories, the primary providers of housing delivery and public housing, are also taking steps. British Columbia, for example, with Vancouver arguably experiencing Canada’s most serious housing crunch, launched BC Builds, a program designed to use under-used land to expand the stock of middle-income housing. All BC Builds projects have a target of middle-income households spending no more than 30 per cent of their income on rent.

The province also says it’s cutting red tape, making it easier for homeowners to add secondary suites and other adjunct shelter, and emphasizing partnerships to build non-market or affordable rentals. BC is also trying to crack down on speculators and others who buy homes but don’t live in them. Those measures include an increase in the foreign buyers’ tax and a new tariff on the profits of selling a home within 730 days of purchase.

Municipalities, at least among levels of government, are seen as the biggest players in housing. They control zoning, land use, urban planning, and must approve housing developments. They’re also responsible for water, sewer and other services that form a costly and time-consuming part of the process for new builds. Many in growing communities rely heavily on the “development charges” from those services.

Municipalities are also where constituents go if they’re unhappy about a new development or zoning change in their neighbourhood, issues that are often heated and capable of getting mayors and councillors elected or kicked out of office.

Paul Smetanin, an economist who has closely followed Canada’s housing market for many years, said development charges soared by about 65 per cent between 2020 and 2024, making them the main component of increased costs in recent years.

To make the affordability issues worse, said Smetanin, president of the Canadian Centre for Economic Analysis, these charges are often calculated per unit, meaning they proportionally hit the buyers of less expensive homes harder.

Rebecca Bligh, president of the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, said she supports Ottawa’s new housing program and its goal of 500,000 new homes a year but that hitting that mark will require a concerted effort and lots of money.

Reducing development charges is possible, Bligh said, but it would require more money from other levels of government. Municipalities across the country already need investments of about $240 billion for roads, bridges, transit, water and other local infrastructure, she said.

Some municipalities have taken recent steps to spur more housing. More than a dozen municipalities in the Toronto area, for example, have temporarily trimmed or eliminated those development charges. Edmonton has tried to address the delays that cost time and money by introducing same-day automated approvals for new detached and semi-detached houses on undeveloped land that meet zoning rules.

And yet, all these recent steps by governments may prove to be lacklustre, when compared to the need.

In a country that has for decades seen rising demand for housing, markets have been thwarted. And still are.

According to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), a Crown corporation that acts as the country’s national housing agency, the supply shortage isn’t about to change any time soon. CMHC recently forecast that the total number of housing starts this year will be about 237,800, down from 245,367 in 2024. Despite all of the attention on this issue, the agency also forecasts a drop to about 227,734 next year and 220,016 in 2027.

So why isn’t supply keeping up with demand so that people can buy the homes they want, in the areas they want to live, at what most would consider reasonable prices?

Like for most products, economists point out, the prices of houses, apartments and condominiums are largely a function of supply and demand. Demand has been high, particularly in urban areas, due largely to population growth. Supply, meanwhile, hasn’t for many years kept pace. That leads to higher prices, with the average purchase price of a new home in Canada now $1.07 million.

And the lack of new homes affects prices across residential markets, even the cost of rent.

When renters who want to buy can’t find an affordable place to buy, they often stay in their rentals, putting the squeeze – and extra demand – on that market. Not surprisingly, Canada’s highest rent-to-income ratios are in Vancouver, followed by Toronto, but they have steadily climbed since the pandemic.

Smetanin said Canada needs to approximately double housing output to stabilize prices.

The federal Liberals’ promise during the recent federal election campaign to increase house construction to 500,000 a year over the next 10 years would mean output of more than double what is now expected for each of the next few years, and a level of residential construction not seen since the years following World War II.

The supply challenge is a blend of factors: a lack of access to land in the right places, lack of skilled trades, and, of course, rising costs.

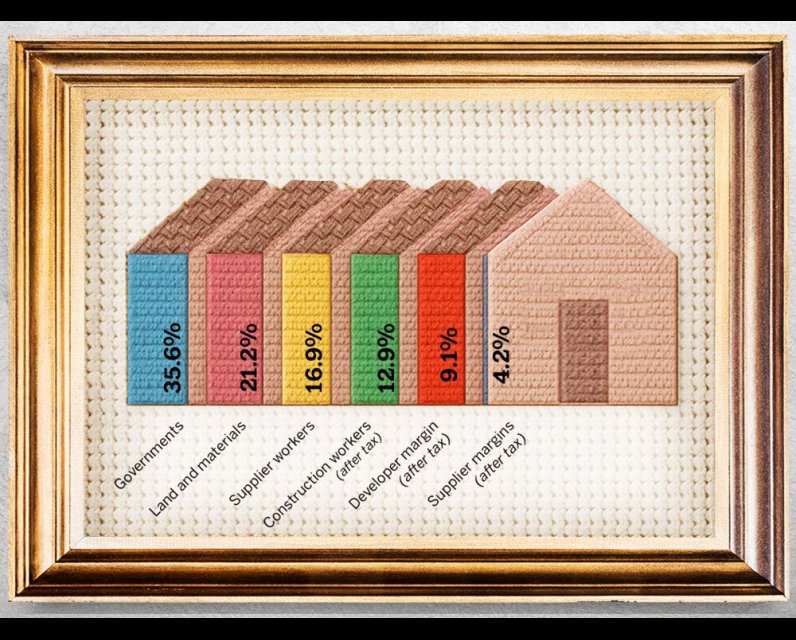

The biggest cost in the price of a new home is taxation, making the three levels of government the top beneficiary of the construction of a new home. Smetanin says taxes and fees now comprise an average of about 35.6 per cent of the price of a new home, which is 16 per cent (or five percentage points) higher than at the start of the decade. About 70 per cent of those charges are for development charges for sewer, water and electricity, land-transfer taxes, and HST. The other 30 per cent is for the indirect income and corporate taxes paid throughout the supply chain, but ultimately passed on to buyers.

But the other major costs that go into a new home have also been on the rise. Those include the value of land and materials (21.2 per cent of the final price), the cost of the workers who provide home essentials such as flooring and cabinets (16.9 per cent), construction workers (12.9 per cent), developers’ margins (9.1 per cent) and supplier margins (4.2 per cent).

Demand, meanwhile, continues to rise, putting further pressure on prices.

Population growth, fueled largely by immigration, internal migration from rural to urban areas, and the reduction in the number of people who live in the average Canadian home are major drivers. Higher pay, interest rates that have remained relatively low for more than a generation and the argument that real estate is a sound investment have also encouraged consumers to buy homes.

“For many families, it’s the major source of wealth creation,” said Royal LePage’s Soper.

Economists and industry executives agree that Canada’s housing crisis has been created over many years of neglect of infrastructure, rising taxes, and other issues, and fixing it will also require at least a decade of concentrated effort.

Smetanin said Canada’s housing sector needs more pre-funded water, sewer, power and transit infrastructure so that land is ready to be serviced. Canada also needs harmonized codes and standards and predictable financing so that developers, lenders, municipalities and tradespeople can plan.

But instead, there are too many players, he said, engaged in too much short-term thinking. Steps can be taken immediately, Smetanin said, but the real solutions are all long term.

“You can’t fix it right away.”

It’s a major problem — not just for housing — when political cycles are shorter than the solution cycles.

And then there’s the lag of perhaps a decade or more between the launch of a new housing policy and people actually moving into new homes connected to that policy. There’s often even a lag of a dozen years or more from when a plot of land has been identified for a new home, subdivision or apartment building to somebody getting new keys. Housing analysts say that timeline is pushed out even further if roads and key services — sewer, water, electricity — need to be added.

Given those horizons, investors and builders can be very cautious.

And recent developments in the condominium market have reinforced that caution. Aggressive building of condos, most notably in pre-construction markets in Vancouver and Toronto, have left some projects unfinished and others scrambling for customers.

While some other condo markets remain tight, some buyers are benefitting from local gluts.

One recent, first-time buyer said she spent only about five weeks looking for a condo before finding pretty much what she wanted in her price range. The Ottawa woman, 30, said she had been following the market for some months and was able to benefit from strong supply and what seemed like a motivated seller.

“It seems like a buyers’ market right now.”

Beyond the jurisdictional quagmire, the current market is also being affected by increased interest rates, higher unemployment, higher labour costs and prices for steel, lumber and other materials, the uncertainty from trade tensions with the United States, slower population growth and a sharp decline in pre-sales. In most Canadian cities, finding convenient and zoned land to build on is also an ongoing challenge, often the most daunting of all.

But the lack of building in Canada represents a loss beyond the social cost.

Economists point out that new homes put downward pressure on housing prices by boosting supply, while also creating economic activity and jobs through construction and the various purchases of furniture, appliances and other items that new homeowners typically make. New buildings are also a major boon for government coffers at all three levels.

And yet, demand has outstripped supply for decades – leaving Canada with what many have described as a housing crisis.

Or, as Eddie, the prospective buyer who has been looking to buy a house in Ottawa for the better part of a year, has concluded: “I thought there would be more options.”

National Post

Our website is the place for the latest breaking news, exclusive scoops, longreads and provocative commentary. Please bookmark nationalpost.com and sign up for our daily newsletter, Posted, here.

Comments

Be the first to comment