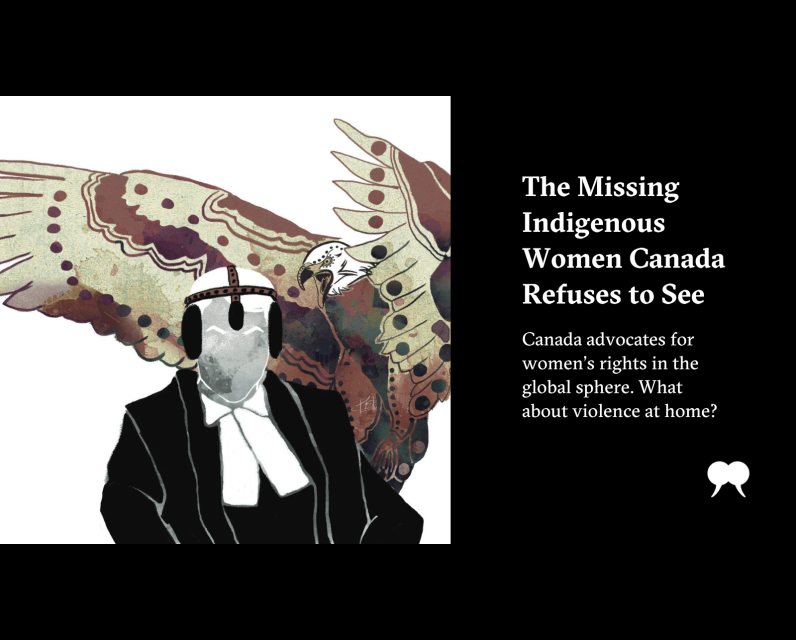

The Missing Indigenous Women Canada Refuses to See

Two things are true about Indigenous girls, women, and gender-diverse people in Canada.

First, as Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg writer Leanne Betasamosake Simpson notes, they “reproduce and amplify” Indigeneity, the definitive characteristics of Indigenous peoples and culture, diverse as they are. Second, she writes, it is this quality that has made them targets of violence in a country that seeks to eradicate Indigeneity.

These truths have especially been on full display in Manitoba since 2022. Following the discovery of O-Chi-Chak-Ko-Sipi First Nation member Rebecca Contois’s remains in a garbage bin outside a Winnipeg apartment complex, at least three more Indigenous women were thought to be in a landfill north of the city. Marcedes Myran and Morgan Harris of Long Plain First Nation and Ashlee Shingoose from St. Theresa Point Anisininew Nation, like Contois, were all described in news reports as vulnerable and street involved. All were also mothers. The convicted serial killer who murdered these women was known to frequent homeless shelters in Winnipeg to search for his victims, his preference being vulnerable Indigenous women whose circumstances were dire.

-

Read more from our Truth and Reconciliation series:

- Intro

- Truth

- Child Welfare

- Economic Development

- Land

- Media

The women’s families and communities pleaded with officials to conduct a search—cries for justice which police and provincial leadership countered with tuts of fiscal feasibility. The tension spilled into the provincial election when the Progressive Conservative campaign claimed there were exorbitant financial and safety costs associated with the search. This debate whether Indigenous mothers were worth retrieving from piles of waste reveals where gender and reconciliation intersect. The public and political indifference to their living and posthumous dignity is rooted in a specific problem: Canadian exceptionalism that touts progressive feminist politics except if you’re Indigenous.

In 1994, Canada sponsored the founding of the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women, its causes, and consequences. A champion for human rights, gender equality, and even a feminist approach to international assistance policy, Canada has been distinguishing itself as an advocate for women’s rights in the global sphere for more than three decades. At home, in 2015, then newly elected prime minister Justin Trudeau proclaimed, “I am a feminist,” appointed an equal number of women and men in his cabinet, and mandated gender-based analysis on all government policy approaches.

Though the position was founded in 1994, the first visit to Canada by the special rapporteur was not until the spring of 2018. In her 2019 report to the UN, then rapporteur Dubravka Šimonović noted Canada’s leadership in gender equity and women’s rights, as well as its declaration as a feminist government, but gestured to a grimmer domestic reality. “Indigenous women from First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities,” the report notes, “face violence, marginalization, exclusion and poverty because of institutional, systemic, multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination not addressed adequately by the State.”

Such is the curious nature of Canada’s enduring existential conundrum: simultaneously a champion and a violator of human rights. Several of the report’s recommendations, like many reports that preceded and succeeded it, call upon Canada to end systemic harms that disproportionately affect Indigenous women and to account for the impacts.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission did not explicitly apply a gender-specific focus. How reconciliation in Canada might be a gendered pursuit is a question that Indigenous women advocated for during the TRC process, but that was not outlined in the Final Report itself. Of the ninety-four Calls to Action, only one focused specifically on a gendered issue: number forty-one, which prompted the Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. Two hundred and thirty-one calls to justice emerged from the inquiry into MMIWG, but six years later, only two have been fulfilled.

Liora Salter and Debra Salco describe “inquiry fatigue” in their 1981 text Public Inquiries in Canada: “Inquiries depend upon the good will of government and departments to ensure that the conditions they propose ‘on approval’ are met.” Reports, inquiries, commissions, and studies into the injustices Indigenous peoples face in this country have all concluded that Indigenous peoples endure interlocking forms of systemic discrimination for which Canada is squarely responsible.

Reconciliation and governmental goodwill to address these issues were absent when Manitoba held public debates over how to offer dignity in the wake of the incredible violence the four Indigenous women had endured, in life and in death. Wab Kinew’s election as premier confirmed what Indigenous peoples have always known: redress and justice for Indigenous peoples do not emerge from mainstream Canada’s moral clarity. It took the first ever Indigenous premier to ensure justice for these women, one of whom is still missing. Reconciliation itself is a lopsided aspiration, with Indigenous peoples—many of them women—doing most of the heavy lifting.

And as Mark Carney’s version of reconciliation holds an economic focus, it’s worth noting that resource development projects—the cornerstone of this economic plan—are epicentres of human trafficking, impacting Indigenous communities and, in particular, women and gender-diverse people the most.

While it’s true that reconciliation without a gendered focus leaves Indigenous girls, women, and gender-diverse people more vulnerable, it is also true that these are precisely the people in our communities who are doing the important work of advocacy, justice seeking, and cultural protection. Their ability to thrive ensures the prosperity and future of our distinct Indigenous nations. Far too many are made vulnerable in systems intent on inaction. As reconciliation shifts to its economic focus, it’s almost as if that’s the point

The post The Missing Indigenous Women Canada Refuses to See first appeared on The Walrus.

Comments

Be the first to comment