Unpublished Opinions

Graeme Boyce, an avid scuba diver and amateur historian, has had a successful career in business as an “agent of change”, and independently writes articles involving the struggle of people. Over the past twenty years, Boyce has participated in the growth of many exciting ventures across several industries, such as travel and tourism, entertainment and media, and new technology.

Currently, he is CEO at Solamon Energy having written its business plan, as well as various strategies and communication plans. His corporate responsibilities over the past five years have included traveling extensively across South Asia, North America and Europe, as well as throughout the Caribbean and Central America to meet leaders, both elected and appointed, advocating the implementation of renewable energy solutions.

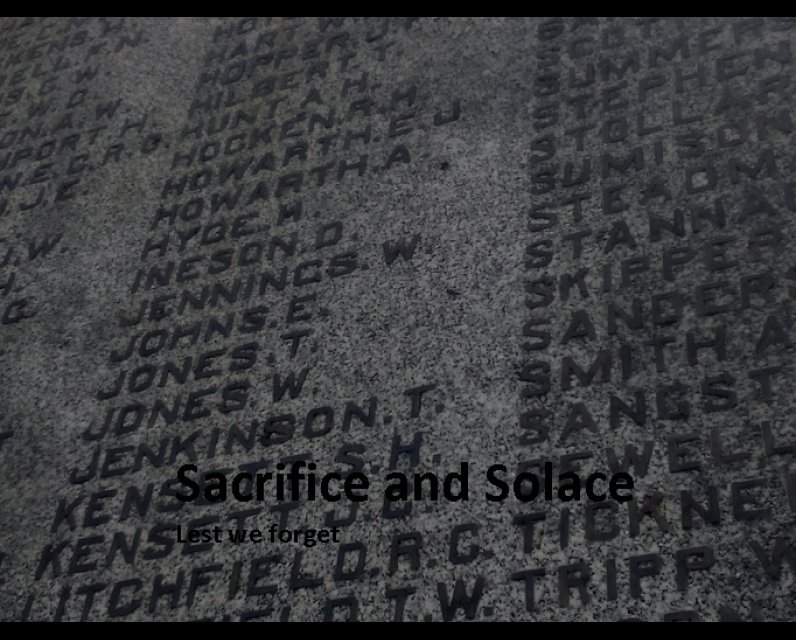

The Struggle for Pacifism: Peace in Our Time

There are many issues affecting people and their nations around the world; most stem from power, as in the power put into people's hands to effect change (and hopefully for the positive) on behalf of their children, and power - as in electricity - and the struggle for power is changing the face of the world, while fossil fuels become extinct and new technologies to power economies are deemed too expensive. A century ago, at great cost, the world was engulfed in a war that consumed 20 million lives and left many millions more homeless - a struggle that erupted over power. In the face of war drums beating ever so loudly, the voice of peace is often not loud enough and easy to ignore. Today, we still tread down the same path and I wonder what we've learned. Lest we forget.

“He who joyfully marches to music in rank and file has already earned my contempt. He has been given a large brain by mistake, since for him the spinal cord would fully suffice. This disgrace to civilization should be done away with at once.

Heroism at command, senseless brutality, and all the loathsome nonsense that goes by the name of patriotism, how violently I hate all this, how despicable and ignoble war is; I would rather be torn to shreds than be part of so base an action! It is my conviction that killing under the cloak of war is nothing but an act of murder.”

– Albert Einstein

Long before the Great War erupted in 1914, having had their sons, brothers and fathers taken forever in a distant fight, pacifists assembled locally and eventually abroad to form organizations and offer peaceful resolutions to potential conflicts arising between nations intent on war. At the outset of the World War One, with hostilities imminent, an international peace convention was actually taking place in Switzerland and many attendees en routewitnessed city streets filled with patriotic celebrations and trains stations with soldiers enthusiastically heading to the frontlines.

Advocating peace, people who opposed war and had traveled to Constance to opine idealistically, nonetheless on August 2 appealed to their respective governments to end the escalating tensions and stop the frenzied mobilization of troops, and also sought the direct intervention of US President Woodrow Wilson to intervene and mediate a solution. Historians today estimate there were approximately 190 peace societies active in Europe at that time who between them published and distributed periodicals in at least ten languages.

In the few months after the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand and his wife in June, the European powers were finished rattling their sabres and officially went to war on August 4, fighting each other relentlessly and at great expense until 1918. Prior, the area known as the Balkans was ruled by the Turkish Ottomans and had for decades been widely disputed. In 1874, Bosnia and Herzegovina had rebelled and two years later Serbia declared war on Turkey. Sarajevo, where the assassinations had taken place, is located in Bosnia which had been annexed by Austria-Hungary in 1908.

Following the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78, at a peace conference hosted by Germany’s Otto von Bismarck, without truly taking into consideration the Balkan peoples, Bosnia and Herzegovina were allowed to be occupied by Austro-Hungarian forces, and Cyprus was given to Britain. Russia’s leaders had sided with the so-called Slavic nations of Eastern Europe seeking independence and desired to unite and in fact rule the Balkan peninsula. While Britain – seeking to maintain control of the vital trade route to India and its Pacific colonies via the Suez Canal (completed in 1869) – sided with Turkey.

By allocating these lands, peace had been achieved, but with the signing of the Treaty of Berlin, the Treaty of Stefano that had been signed three months earlier by Russia and Turkey was effectively replaced. The victorious Russians who had relieved the Ottomans of their territorial possessions in Europe now found their influence greatly diminished. Upon leaving Berlin, the leaders of Europe were satisfied, though many others were not, including those among the Russian and Ottoman empires. Underlying their goals, was the issue of religion – noticeable in Bulgaria.

Planting seeds for the World War One, the effects of the Treaty of Berlin were anything but peaceful, as Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro were declared independent principalities. Meanwhile Russia “kept” South Bessarabia, which it had annexed in its war against Turkey, though the Bulgarian state it had created was split into the Principality of Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia, both of which were given nominal autonomy under the control of the Ottoman Empire, where the Turkish government were obliged to guarantee the civil rights of non-Muslim subjects.

On one hand there were those individuals who enjoyed power and could enforce peace, for the benefit of their nation by “wielding a big stick”, an ideology proposed by then-US Vice President Theodore Roosevelt in 1901, and on the other there were those who opposed violence in general as dictated by their conscience or their religion, such as Mennonites and Quakers. In between, there were groups from socialists who opposed war based on its capitalist agenda, to scholars and philosophers who argued any dispute could be settled amicably and hence war is unjustifiable.

The Napoleonic Wars had ended in 1815 with the dramatic defeat of the French forces at Waterloo. Leading up to their victory, however, the British government had received no less than sixteen peace petitions and faced many public anti-war demonstrations. After the war, in 1816, the London Peace Society was formed, which was originally known as The Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace and then, after merging with the International Christian Peace Fellowship in 1930, became the International Peace Society.

It was the London Peace Society who convened in 1843 the International Peace Congress seeking peaceable arbitration in the affairs of nations and the creation of an international institution to achieve those objectives. Nevertheless, Britain throughout the 19th Century would continue to fight overseas, sending its army and navy to India, China, Burma, Iran, Afghanistan, Crimea, New Zealand, West Africa and South Africa. Subsequently in Britain, after the outbreak of WWI, religious groups, libertarians and elements of the antiwar movement created two new pacifist organizations: the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the No-Conscription Fellowship.

In 1889, the inaugural Universal Peace Congress had taken place in Paris, yet people representing many organizations from many countries had been assembling annually since the first peace congress had taken place in London. Fredrik Bajer, a Dane, eventually established the Permanent International Peace Bureau (PIPB), which comprised a coalition of like-minded groups who demanded not only disarmament and an international court, but also mandatory arbitration to settle disputes between states. The PIPB were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1910 for their efforts.

Throughout the 1800s many people across America were also involved in both pacifist and antiwar movements. Perhaps the most notable was the American Peace Society, which formed in 1828 and organized many peace conferences while publishing the Advocate of Peace. Before the Civil War broke out, prominent intellectuals of the time, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and William Ellery Channing also contributed literary works against war. As well, during the Civil War, riots erupted in New York in opposition to conscription proposed by President Lincoln. Further, George McClellan ran for President as a “Peace Democrat” against the incumbent Lincoln.

Be assured, women contributed their voices to the antiwar movement during World War One. As Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, a well-known activist in Britain, explained:

“The bedrock of humanity is motherhood…Men have conflicting interests and ambitions. Women all the world over, speaking broadly, have one passion and one vocation, and that is the creation and preservation of human life. Deep in the hearts of women of the peasant and industrial classes of every nation, there lies…a denial of the necessity of war.”

At the outset of the Great War, in Britain the League of Nations Society was formed and in America, likewise, in 1915 the League to Enforce Peace was created – with leaders of both groups hoping an international organization could find a peaceful resolution to the on-going and intensifying conflict. Germans, too, were neither immune to nor could contain antiwar and pacifists’ sentiments.

And so one of the most influential Germans in the world and Nobel Prize winner, Albert Einstein, as a young scientist, openly challenged the authority of government and opposed the war. “It is my conviction,” he concluded, “that killing under the cloak of war is nothing but an act of murder.”

Adding to his voice, the war deeply disturbed Clara Zetkin, a longtime leader of the international socialist women’s movement in Germany. Critical of the Social Democratic Party’s support of the war and perceiving men’s inaction generally, she decided that women had to take up the peace cause.

“If men kill,” Zetkin said, “women must fight for peace.”

At an international meeting of antiwar socialist women in Berne, Switzerland, in February 1915 Zetkin issued a peace manifesto which declared that the war constituted imperialist aggression to enrich the armament makers and other capitalists, and proclaimed that “the workers have nothing to gain from this war, they have everything to lose, everything, everything that is dear to them.”

According to Wikipedia, during the Great War, “the war to end war”, the total number of deaths includes about 11 million military personnel and about 7 million civilians. The Triple Entente (also known as the Allies) lost about 6 million military personnel while the Central Powers lost about 4 million. At least 2 million died from diseases and 6 million went missing, presumed dead.

Comments

Be the first to comment