Stay informed

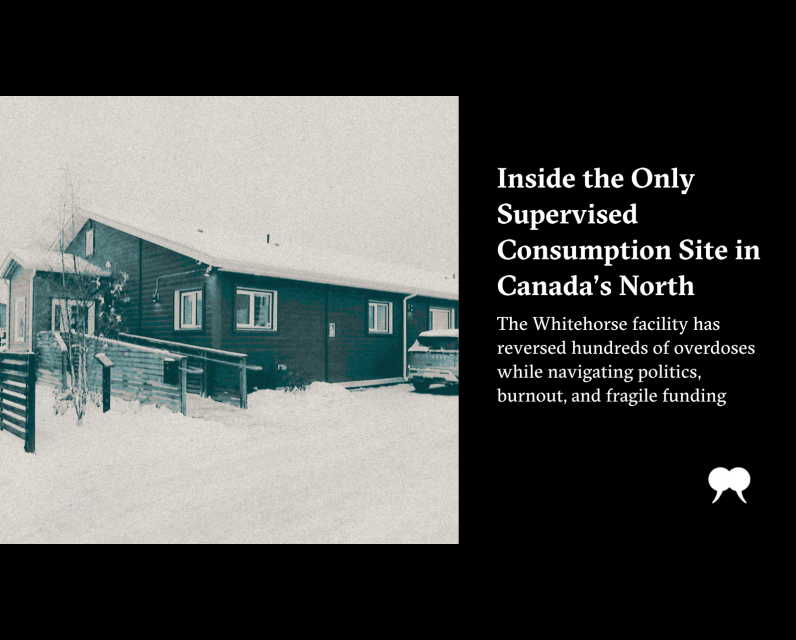

Inside the Only Supervised Consumption Site in Canada’s North

If you show up at 6189 Sixth Avenue, in Whitehorse, you’ll ring a doorbell to be let in. To protect your privacy, you’ll be asked to pick a code name—favourite movie characters or favourite foods are popular choices. If it’s your first visit, you’ll do a brief intake at the welcome desk, where staff will ask if you have any medical conditions or have had any bad drug reactions. They’ll also ask which drug you’re using that day, and whether you’d like the substance checked to confirm that you’re consuming what you think you’re consuming.

Then you’ll queue for one of the three tables in the smoking room or one of five injection booths. Here, smoking dominates—about 95 percent of consumption is by inhalation. Crack cocaine is the substance of choice, followed by crack with fentanyl, then fentanyl.

The smoking room has three stainless steel tables and an intercom. Staff supervise through a large window. You can play whatever you want on the radio. A magnetic timer on a whiteboard counts down your allotted ten minutes, after which you’ll be asked to stay another half hour so that workers—trained in first aid, CPR, and basic life support—can monitor you. You’ll then be ushered into the “chill-out space,” with armchairs, two desktop computers, a TV on the wall, and coffee and water. There are airplane neck pillows or the choice of two recliners, selected because they keep your head tilted back and airway open as you nap.

The entire design is intentional: people come in alive, and they leave that way.

Blood Ties Four Directions Centre operates the only supervised consumption site in Canada’s North, and it’s become a critical line of defence against overdose deaths. The opioid crisis has hit the Yukon hard—harder than the Northwest Territories and Nunavut. According to the territory’s coroner, 120 people died from toxic substances between 2020 and 2025; 104 of those deaths involved opioids. In 2022, after twenty-five deaths the previous year, the Yukon government declared a substance use health emergency.

Blood Ties’ supervised consumption site is a key part of the emergency response. An average month sees 2,000 to almost 4,000 visits (many from returning clients). Since it opened four and a half years ago, staff have reversed more than 440 overdoses. “I used to Narcan people in the snow outside of our old building,” says Blood Ties’ executive director Jill Aalhus, referring to the drug used to reverse near-fatal episodes. She doesn’t have to anymore.

Blood Ties offers two paths: referrals to detox and treatment for those ready to quit and harm reduction for those who aren’t. Research shows the method works. It curbs public drug use, cuts infection risk, and eases the strain on emergency rooms. And yet supervised consumption sites sit at the centre of a polarizing national debate over how addiction should be handled. Blood Ties shows what’s possible when evidence is allowed to lead.

Blood Ties started with a small roster in the early ’90s, focused on HIV education. Today, it employs thirty-three people and has expanded into a one-stop network of care. “We want to save lives, and that’s a huge piece of it,” says Aalhus. “But we also want people to have quality of life.”

The organization runs a needle and pipe exchange, distributes naloxone kits, and provides housing support, wellness groups, daily meals, and warm clothing. It also offers basic health and hygiene supplies—tampons, condoms, pregnancy tests, soap, and toothpaste. All of these services, including the supervised consumption site itself, operate out of the same building, an elongated, one-story former care home in downtown Whitehorse.

The supervised consumption site was the product of an April 2021 confidence and supply agreement between the territorial Liberal government and the Yukon New Democratic Party. It opened four months later. Aalhus recalls a handful of heated, town-hall-style meetings, with some residents questioning whether the site was even necessary in a small city like Whitehorse. Rumours followed; that Blood Ties was handing out drugs (it isn’t), or that the building functioned as a party house (it doesn’t). To counter the misinformation, the organization has opened its doors for community tours. “I think when people are able to come in and see the service,” she says, “most of them are like, ‘Oh, yeah, this is a health care facility.’”

Supervised consumption sites are a partisan football. In the lead-up to the last federal election, Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre called them “drug dens,” while Ontario cut funding to several in 2025, opting to fund new treatment centres instead. Alberta has closed sites in Red Deer and Edmonton, and just before Christmas, Premier Danielle Smith announced plans to shutter a Calgary location. “It was an experiment,” she said. “It didn’t work.”

In the Yukon, the mood is different. The conservative Yukon Party, elected in November, campaigned on recognizing the “ongoing role” of harm reduction. And when the issue resurfaced in the legislature in December, health and social services minister Brad Cathers said there were no plans to change how the programs are delivered.

Political backing, however, doesn’t soften the realities of the work. At first, the supervised consumption site was open five days a week, with about 900 visits a month. When it expanded to seven days in 2024, visits increased threefold. In April 2025, Yukon Royal Canadian Mounted Police were called after a report of a gun. The building was evacuated, two women were arrested, and police determined the weapon was a replica. The fallout was immediate: one-third of the staff resigned, and the site scaled back to five days.

The incident magnified existing issues of low wages and burnout. “The cumulative impact of grief, trauma, and exposure to violence can be really challenging,” Aalhus says. When “coupled with the uncertainty of the work and the political rhetoric that makes this into a moral conversation,” she adds, “it can be really draining for people.”

Unstable funding doesn’t help. This past fall, the Council of Yukon First Nations stepped in with money that allowed the site to operate daily again. But that support is set to expire this spring. A consistent schedule is critical, says Aalhus, because visitors may not know what day of the week it is. Any closure disrupts routine. In an ideal world, she adds, the site would be open around the clock. Blood Ties has met with the newly elected territorial government about future funding; Aalhus says talks have been positive.

Still, the model has limits. “Supervised consumption sites can’t carry the weight of a structural crisis on their own,” Aalhus says. She calls them a band-aid solution—an effective one—to a problem grown out of control after years of government inaction. What’s missing, she argues, is a response that isn’t siloed: one that includes an accessible, regulated safe drug supply, culturally relevant treatment, evidence-based drug policy, and safe, affordable housing.

Only by confronting the problem at full scale, Aalhus says, can Canadians grasp what it actually is: “the worst public health emergency Canada has ever seen.”

With thanks to the Gordon Foundation for supporting the work of writers from Canada’s North.

The post Inside the Only Supervised Consumption Site in Canada’s North first appeared on The Walrus.

Comments

Be the first to comment