Unpublished Opinions

A former federal civil servant (Foreign Affairs) and consultant, Terrence Lonergan lives in Ottawa and is active in local and community affairs.

A Modern Library for Ottawa (Part 4)

Part 4. The Modern Library is also a Knowledge Factory

Over the week, I have submitted to Unpublished Ottawa three short essays on Ottawa’s next Central Library.

We now come to the fourth and final paradox that defines the Modern Library.

………………………

Fourth paradox:

Though people will less and less learn from books, libraries will be more closely connected to the acquisition of knowledge.

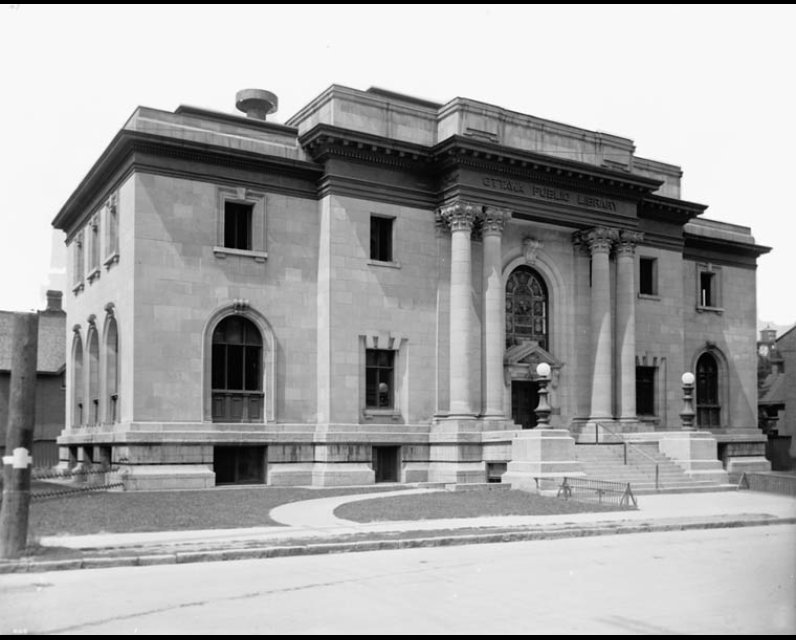

Each of us lives in his own world, a space defined by all the things so far learned (whether seen, heard, or read) and not yet forgotten. Knowledge flows from experience and can’t be divorced from it. A person living in Ottawa in 1906, at the time the original library was inaugurated, would undoubtedly have known much about city and region, less about province and country, and little about the Americas and other continents. He would have gathered his information from a narrow network of family, friends, acquaintances and co-workers, from a mostly short education, from local newspapers, the radio, a few films (newsreels only began in 1910), and occasional encounters with visitors or foreigners.

The brand new Ottawa Public Library would have brought him a breath of fresh air and, despite a modest initial collection, deepened and broadened his knowledge. That’s because books can contain stories about anything at all, from the most mundane to the exotically esoteric and each and every one of these stories will stick around until we are ready to hear it.

Books convey information and transfer knowledge slowly but effectively and, until very recently, a good set of books was the only way to achieve a reasonably accurate understanding on technical, social, economic or political matters, and solidly underpin one’s opinion, decisions, actions, and participation in civil society.

It’s good to remember that, for any of our city's resident and from 1906 to 1996, a span of 90 years, there were few better places than Ottawa’s Public Library to open up the mind, fire the imagination and fill the head with all kinds of useful facts.

However, in the last two decades, our relentless, every minute every second, exposure to advanced technology (think of it as information technologies, plus mass media, plus a transportation revolution) has convinced us that all existing human knowledge now lies at our fingertips, ours for the asking.

And though today the Library still serves as a unique and rather remarkable knowledge factory, we have begun to convince ourselves that libraries (along with our old bookish ways) have lost their standing and are, therefore, less relevant.

If so, we may have reached the wrong conclusions.

I could substantiate my point in many ways but will focus only on four major shortcomings of the World Wide Web.[i]

First: The World Wide Web is an ocean and drowning is easy.

Computers and the Internet have dumped the whole wide world at the doorstep. In Canada, or any other advanced countries, it is now routine to mainline information. In 0.41 seconds, the string of words “Ottawa Public Library” typed in the entry box of a search engine results in 9,970,000 popups. Modern computers work blazingly fast and sitting in front of them can be exhilarating.[ii]

Then again, it would take forever to sift through all the documents that have fallen in my lap. Every technology has its Achilles heel and computers are notoriously clumsy and undiscerning. Immensity and disarray sum up the Web’s fundamental weakness and foreshadow the tragic fate that awaits anyone foolhardy enough to seek knowledge from a system that will never understand what enough or pertinent means.

It makes matters only worse that most first pages hits contain only sound-bite information. Ever since television and the news media introduced the 10 seconds clip, Canadians have been plunged in an ocean of compressed sights and sounds.

Malcolm Caldwell calls the ‘Blink’ effect the brain’s apparent ability to snatch meaning in a split second. Whether the mind does catch something real or not, the experience is apparently striking enough to lead many people to believe that learning and knowledge consist of a series of these mini-bursts of insight.[iii]

Wikipedia illustrates perfectly the nature and limits of the blink. Judging from how frequently that website tops the list of results, a casual observer might think that Google, Yahoo, and Bing consider the encyclopaedia the ultimate source of universal truth. However, as anyone familiar with Wikipedia knows, its entries merely provide a Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

Wikipedia has considerable merit, notably as an ongoing Community project that brings together thousands of volunteers. However, and I say this without prejudice, its encyclopaedia has limited value, being adequate only for quick enquiries that can be answered with a barebones reply.

Unfortunately, in innumerable instances the response needs to have flesh on its bones. In order to be useful, it must far exceed what can be surmised from blinks.

Second: The World Wide Web is a maze.

The World Wide Web comes with no instruction manual, offers no on-site guidance, suggests no logical pathway to address an issue efficiently and effectively, and has no idea what beginning or end mean. A browser opens an extremely large window on the universe but it invariably leaves you stranded on the sill. And since the scale has grown from mega, giga, to tera in a matter of years, the Internet maze now stretches beyond the horizon, to form a universe within the Universe.

The Internet was not designed organically and does not possess the property to self-generate its structure and self-organize its contents. As a result, nothing functionally links to anything else. Like a mosaic, or a pixelated image, the Web is devoid of any pattern until an onlooker creates one.

It is theoretically possible to fathom the Web, with high-speed computers working in parallel. We already have examples. Programmes called Crawlers (Google calls them Spiders) sift through documents, tally key words and inventory each significant word in a given language.[iv]

The resulting index constitutes the domain that, for instance, the Google search engine analyses for contents on the basis of a word and link based methodology. In any type of Internet search, we access not the entire web but the subsection that crawlers have so far indexed. Furthermore, documents presented to us are chosen and listed in accordance with very specific parameters. When it looks at a webpage, Google’s PageRank does not evaluate the quality of its contents but merely attributes the page a value calculated from the number of links to it originating from other sites (whether meaningfully related or not). The system therefore uses popularity as a proxy for significance and implicitly contributes to the creation of celebrity websites, such as Wikipedia.[v]

Google and all the other search engine companies must proceed in this or very similar ways. They have no choice. The Web is too vast and grows too rapidly to ever be sorted out by human intelligence. It is impossible to inject a nano-gram of human judgment in an online query when the results appear in a fraction of a second. Confronted each time with an astronomic number of hits, we are left to separate the wheat from the chaff by ourselves, to cut our own path of meaning and significance through the maze.

To make matters even more complicated, on every result page, at every step, a kaleidoscope of titles, pictures, applets, and links tempts us to jump to another idea or website. In every WWW connection, whatever the search string, one inevitably encounters a salesman keen on making a dollar.

So before entering the maze, in 2015 as in 550 B.C, it would be wisest to take along a spool of Ariadne’s thread.

Third: The World Wide Web accentuates our inherent biases.

A year ago, I went along with Goodreads’ request and provided numerous examples of books I had read or have an interest for. Ever since, I receive proposals to purchase new books that ‘fit my profile’. My love for science fiction, politics, and detective stories has defined a persona that I am invited to enlarge, to grow into.

The particular persona that Goodreads attributes me is not alien to me, quite the contrary. But it does not capture, at least not yet, all the aspects of my identity, all the ambiguities and contradictions of my personality.

I am being nudged to indulge in my own preferences, which is very seductive. Dangerous too: I was subject to the tendency well before I started surfing on the Web.

In the course of normal life (I make an exception for the residents of gated communities surrounded by people who could be their clones), the average individual will from time to time encounter people of opposite viewpoints. Any neighbourhood community meeting I have attended has provided a perfect illustration of this phenomenon.

Like many, I dislike being confronted with contrary ideas and even more to be proven wrong. It tastes as bad as medicine.

Unfortunately, it’s just as salutary. Knowledge is born from the careful consideration of all valid, rational viewpoints. I may disagree with what you say; nevertheless it will likely enlighten me to listen.

Alas, no opposite perspective ever pops up in the multitude of ‘fit my profile’ websites. In the Internet, the unaware are constantly at risk of being sucked into virtual gated communities where one-sided information, filtered and massaged to ‘fit a profile’, will reinforce their prejudices. I’d wish the Web had not rediscovered sycophancy and partisanship, but it has.

Fourth: Like Nature, the World Wide Web has no moral intent.

Nature is not a safe environment for the ignorant, the naïve or the unprotected. Not all plants are good to eat, not all animals make good pets. Like it or not, Hobbes was not mistaken in his description of the state of nature: ‘No arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death: and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’.[vi]

The Internet may be Man’s creation rather than the result of chance and necessity, but it betrays the same lack of moral intent. Viruses, Malware, Spyware, Scam E-mails, Data-theft, Pornography, Cyber-bullying, Compulsive Gaming, Online Predators, Gossip and Slander, the list is hardly complete. There is a lot of evil out there and we all should beware of booby-traps.

……………………….

I don’t want to belabour my point. I love computers and surf the Web as much as people half my age do. But I don’t think that the Web, as it now exists, is a reliable, or entirely safe, source of knowledge.

Which is really appalling because the 21st century has thrown at us a number of mega-problems such as climate change, industrial pollution, exploitation of natural resources, massive extinction, as well as the obligation to manage a whole set of complex global systems (e.g. peace and security, global finance, international trade and commerce, air transportation, maritime shipping, weather monitoring, postal services, etc.) The world has become a global community but still not found out how to run itself as one.

As I stated at the outset, libraries have traditionally acted as a significant knowledge factory. It’s not hard to understand why. When school days have ended, after teenagers have matured into adults, how and where do they learn?

By and large, individual will and personal effort are the drivers behind both continuing education and adult learning. The new technologies have not altered that equation.

So what choices do Ottawa residents (if not all Canadians) really have? How do the present generations of adults achieve and maintain a reasonable level of 21st century functional literacy?

Today’s unstructured, disorganized World Wide Web fails to offer a more modern, more efficient, better-adapted path to the acquisition of knowledge. The World Wide Web may eventually transcend itself into a knowledge factory but that will take time and will depend on a considerable intellectual investment on the part of many, many human beings.

All this leaves us up the proverbial creek. In retrospect, it was probably not very smart to let old and trusted public learning institutions such as libraries fall behind the times.

But rather than bemoan our fate, let’s recognize that we live in an age of major change. Why not embrace the metamorphosis? Why not take strong, decisive measures to ensure that Ottawa’s Public Library stays abreast of new technologies, new lifestyles and values, that it remains as good a knowledge factory as ever, that it becomes even better?

Terrence Lonergan

Ottawa

....................................

[i] In this essay, I have used Web, and World Wide Web to describe the global information system of interlinked hypertext documents and Internet to designate the hardware and software systems and the physical network that generate the Web. I am primarily interested in the contents: documents and information, though of course I recognize the technology and physical structure as a magnificent engineering and conceptual achievements.

[ii] Query on Google Search for “The Modern Library” made on 10 March 2015. The string of words is actually ambiguous and many of the first page results relate not to a modern library but to a set of classic books published by an American publishing company called The Modern Library.

[iii] Caldwell, Malcolm: Blink : The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, Little, Brown and Company, Boston (2005)

[iv] A quick introduction to Google’s crawling and indexing system and methods can be found at : http://www.google.ca/insidesearch/howsearchworks/crawling-indexing.html (Website accessed 22 march 2015)

[v] A more fulsome description of the Google Pagerank system is available, inter alia, at http://searchengineland.com/what-is-google-pagerank-a-guide-for-searchers-webmasters-11068 (Website accessed 10 March 2015)

[vi] Hobbes, Thomas (1588-1679): The Leviathan, or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Common Wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil (1651).

---------------------------

Comments

Be the first to comment