Unpublished Opinions

Eva Schacherl is a writer with a life-long interest in health and environmental issues. She has decades of experience in management and communications, in both the federal government and non-profit organizations concerned with the environment, social justice, youth and mental health.

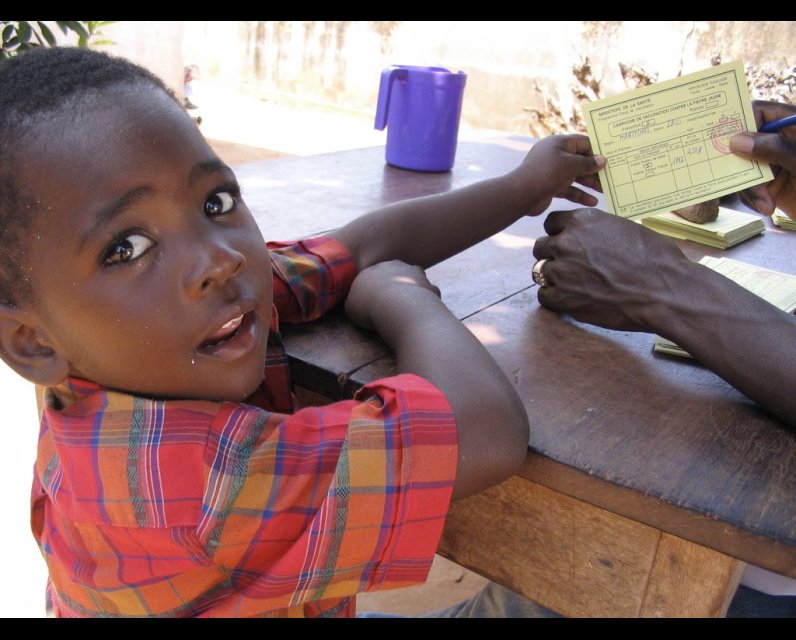

Northern countries need to avoid COVID colonialism

University of Ottawa epidemiologist Raywat Deonandan proposed recently that the world undertake a global ‘Manhattan Project’ to flood the world with COVID vaccines.

This sounds like a rich countries’ plan, with low-income countries as the ‘target’. After decades of development strategies for ‘Third World’ countries, we know that top-down approaches fail because they do not consider what people actually want and need. Any strategy based on rich countries’ interests – commercial, medical or scientific – is just another form of the colonialism that has caused so much harm.

Deonandan invokes the creation of the atom bomb. (You know, the one that led to a world with 60,000 nuclear weapons during the Cold War, and that still hangs over our heads with the threat to end human life.)

But is ‘making war’ on the COVID-19 virus at the top of African or Asian nations’ priority lists? When you order the world’s countries by lowest per capita deaths from COVID-19, here are the 10 with the lowest rates: Burundi, China, New Zealand, Chad, Niger, South Sudan, Tanzania, Congo, Tajikistan and Benin. The next 40 countries with the lowest COVID death rates include 29 in Africa and 8 in Asia. The only ‘rich’ countries with such low rates are South Korea, Australia and Singapore.

If we look at Kenya, one of Africa’s more affluent countries, the top cause of death in 2019 was HIV/AIDS, and the top driver of death and disability was malnutrition. With a population of 52 million, Kenya has had 5,348 deaths attributed to COVID, while HIV causes 17% of its 285,000 annual deaths. Canada, meanwhile, has had 29,964 COVID deaths, a rate of 790 per million – almost 8 times Kenya’s and 240 times Burundi’s rates.

Meanwhile, the top 10 highest rates of COVID deaths, aside from Peru and Brazil, are in European countries, ranging from 2,900 to 4,000 deaths per million. They are East European countries, but we don’t have to go far down the list to find the USA, Belgium, Italy, the UK, Spain and France. The point is that COVID seems to be a major 'First World' problem, with death rates from 1,000 to 4,000 per million – up to 40 times greater than Kenya’s and 1,200 times that of Burundi.

Why is this? A medical researcher from Nigeria, Yakubu Lawal, compared population and COVID data from a number of African and Western countries and found that lower COVID mortality seems to go along with a younger population and with a higher pre-COVID death rate from cardiovascular disease. Rich countries’ more advanced healthcare systems leave “a larger pool of persons surviving and living with CVD [cardiovascular disease] who eventually become susceptible to COVID-19 death.”

Lawal’s conclusion: “there should be no ‘one solution for all’ when it comes to balancing COVID-19 restrictive and socioeconomic policies.”

Contrary to Deonandan’s image of poor countries suffering from crowding and “poor ventilation,” people in warmer and less industrialized countries spend more time outdoors or with open windows. Poor ventilation is our northern countries’ problem, not theirs. Different cultures and economic realities in many parts of Africa and Asia mean that elderly people often live with their families rather than congregated in long-term care institutions. Again, the latter is a 'First World' problem that has accounted for over half of Canada’s COVID deaths.

The first response to the omicron variant stigmatized African countries as a source of disease – even though it was quickly found to be in Europe and North America. The HIV/AIDS pandemic has shown that waging war on a virus while stigmatizing and discriminating against its sufferers, and ignoring social and economic inequalities, does not work. Alex de Waal’s recent book, New Pandemics, Old Politics, shows the harm done by the war metaphor applied to pandemic diseases over the past 200 years. Our war mentality not only fails to control pandemics – it has often created them in the first place.

So before we go swinging in as 'saviours' for low-income countries, we had better wait to be asked. The billions or trillions that could be spent “flooding the world with COVID vaccines” could also be spent in other ways that contribute to the health of the world’s population (and help prevent future pandemics), from providing primary health care to restoring environmental damage. While some low-income countries may want better access to COVID vaccines and medicines, this can best be done by suspending patents to lower their costs – something India, South Africa and other countries have called for. We must let all countries choose the strategies most effective for their own conditions.

If there is a global rallying cry to end the current crisis, it should not use a “wartime mindset”, but rather one that builds a peaceful world and better relations among nations. It should not be all about us.

Published January 3, 2022 in The Hill Times

Photo credit: Creative Commons, Sanofi Pasteur vaccination drive

Comments

Be the first to comment