Unpublished Opinions

Lynn is an Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe from the Ottawa River Valley, Ontario, Canada. She describes herself as a learner-researcher, thinker, writer, Black Face blogger, and she has been an Indigenous human rights advocate for 25 years. Lynn works to eliminate the continued sex discrimination in the Indian Act, and she is also an outspoken critic of the contemporary land claims and self-government process. She has a doctorate in Indigenous Studies, a Master of Arts in Canadian and Native Studies, and an undergraduate degree in Anthropology. She also has a diploma in Chemical Technology and worked in the field of environmental science for 12 years in the area of toxic organic analysis of Ontario’s waterways. While advocating for change is currently part of what she does, she is also interested in traditional knowledge systems that guide the Anishinaabeg forward to a good life.

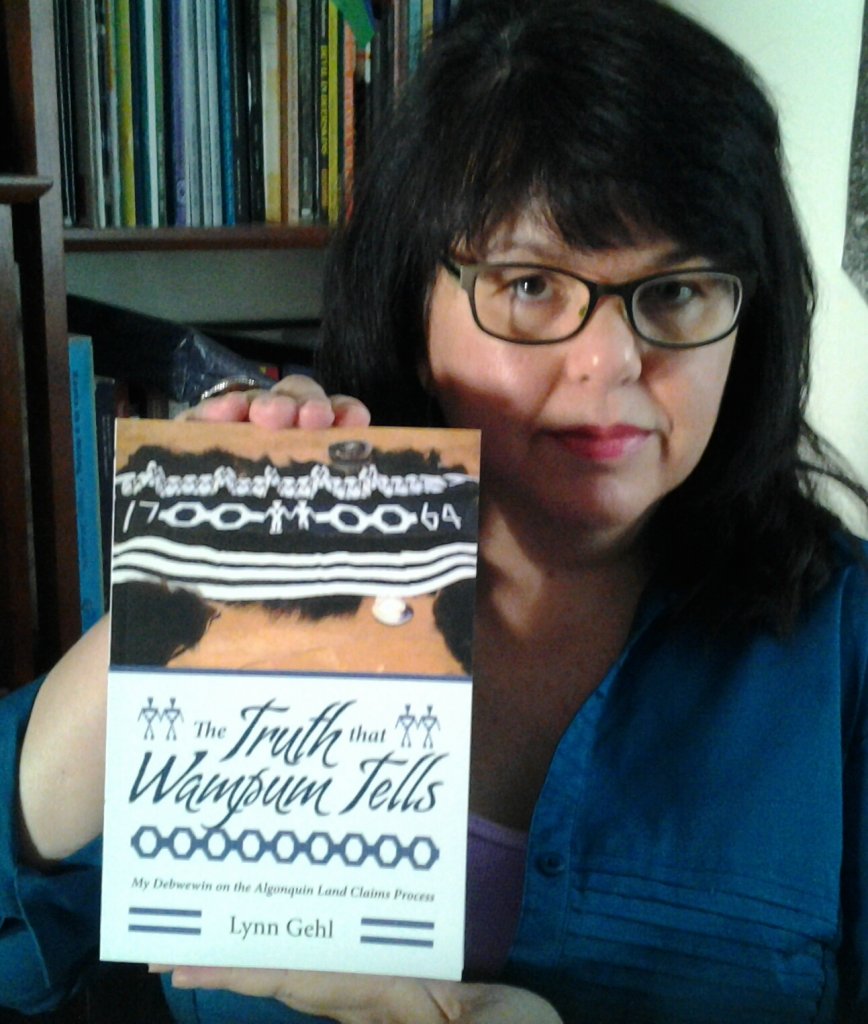

Along with many journal and community publications, she has three books:

Anishinaabeg Stories: Featuring Petroglyphs, Petrographs, and Wampum Belts

The Truth that Wampum Tells: My Debwewin on the Algonquin Land Claims Process

Mkadengwe: Sharing Canada’s Colonial Process through Black Face Methodology

Open Letter to Minister of Indigenous & Northern Affairs: Canada’s Constitutional Beginnings and the Rights of Indigenous Nations

Re: Canada’s Constitutional Beginnings and the Rights of Indigenous Nations

Kwey Dr. Bennett, Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs;

Congratulations on your appointment as the Cabinet Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs. I have read the letter that outlines your mandate that the newly elected Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has ascribed to you.

As an Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe eager to experience genuine and meaningful change in the relationship between Canada and Indigenous Nations I was particularly happy to read that PM Trudeau is willing to enter into nation-to-nation relationships with Indigenous Nations. In your mandate letter PM Trudeau states this nation-to-nation promise on three occasions:

- No relationship is more important to me and to Canada than the one with Indigenous Peoples. It is time for a renewed, nation-to-nation relationship with Indigenous Peoples, based on recognition of rights, respect, co-operation, and partnership.

- As Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs, your overarching goal will be to renew the relationship between Canada and Indigenous Peoples. This renewal must be a nation-to-nation relationship, based on recognition, rights, respect, co-operation, and partnership.

- I expect you to re-engage in a renewed nation-to-nation process with Indigenous Peoples to make real progress on the issues most important to First Nations, the Métis Nation, and Inuit communities – issues like housing, employment, health and mental health care, community safety and policing, child welfare, and education.

What most Canadians and Canadian parliamentarians do not know is that Canada’s constitutional beginnings did not begin in 1867 with a room full of English and French patriarchs in a top down approach. Rather, Canada’s constitutional beginnings predate this moment to a time when the 1763 Royal Proclamation was ratified during the 1764 Treaty at Niagara. The Treaty at Niagara established a treaty federal order where Indigenous Nations retained the jurisdiction of their land and resources according to their own governance traditions. This treaty federal order is recorded in three wampum belts as well as remains within the oral tradition and thus hearts and minds of Indigenous people. It was in 1867 when this was unilaterally changed and a provincial federal order was imposed on Indigenous people and imposed on Indigenous land; and where the treaty federal order first agreed upon in 1764 was denied. Further, it was here where Canada unilaterally granted all Indigenous land as Provincial Crown land and the nation-to-nation relationship was dismissed.

As Canada did this to Indigenous Nations, Canada also criminalized our culture, denied us the right to vote in their political system, and also denied us the right to hire lawyers. While these particular oppressive measures have changed, in the area of Indigenous jurisdiction and a genuine respect for a nation-to-nation relationship with us, there has not been any movement beyond political rhetoric and manipulation.

It was after the 1973 Frank Calder decision when Canada finally manifested their comprehensive land claims policy titled the 1981 In All Fairness: A Native Claims Policy which remained steeped in the colonial agenda of Indigenous denial rather than the nation-to-nation relationship established at Niagara in 1764. In short, in this policy Indigenous Nations were forced to comply with a blanket extinguishment of all their rights. This outraged many Indigenous people where eventually Canada tweaked their comprehensive land claims policy text and subsequent practices into a “new” policy titled the 1987 Comprehensive Land Claims in a way that Indigenous Nations were forced to relinquish only their land and land related rights versus all their rights. It is easy to rationalize that these requirements render Indigenous nations with next to no agency and next to no ability to live a good life as it is through the gifts (resources) of the land and water that nations are able to construct meaningful governance structures and traditions.

Many Canadians know about the Tsilhoqot’in Supreme Court of Canada decision rendered June 2014. Subsequently, in an effort to reconcile law with policy Canada put forward their “new” interim comprehensive land claims policy. Shortly after, Bruce McIvor offered his legal analysis presenting four main issues that remain colonial and thus problematic: First, it “disregards the need for high-level discussions between Canada and First Nations leadership to reframe the approach to achieving reconciliation on Aboriginal title and rights claims”; Second, it “fails to acknowledge that recognition of Aboriginal title must be the starting point for all negotiations and agreements between Indigenous peoples and the Crown”; Third, it “fails to address the need for the Crown to seek and obtain the consent of Indigenous peoples before making decisions that will affect Aboriginal title lands”; And fourth, it “fails to consider and adhere to the underlying principles of Aboriginal title”; and it “imposes a unilateral approach which is inconsistent with Canada’s fiduciary relationship to Indigenous peoples and its obligations to act in good faith in negotiations concerning Aboriginal title and rights”.

The short story is that despite several policy revisions and a favourable SCC decision Canada’s approach refuses to meet new law, remains rooted in colonial Canada’s agenda, and fails to genuinely value the nation-to-nation relationship established at the 1764 Treaty at Niagara.

What does this mean in practical terms? This means Indigenous Nations such as the Algonquin Anishinaabeg are currently forced into a process where, as Russell Diabo clearly argues, they have to terminate their land and land related rights.

Through Canada’s termination policy agenda Canada is offering the Algonquin Anishinaabeg in Ontario only 1.3% of their land and a one-time buy out of $300 million. This is the reality imposed on us despite Indigenous efforts to take the matter all the way to the SCC. There is so much wrong with this. First, it ignores court decisions, second, it denies the nation-to-nation relationship, third, it denies Indigenous Nations the right to maintain their own jurisdiction of their land and resources in a manner that provides them with their own resources to then construct meaningful governance bodies and mechanisms such as the right to generate an income from their land and water ways. There is no need for Indigenous nations to be dependent on the purse strings of oppression. We are capable Nations, with capable members, capable of making our own decisions. This last statement is not to deny the need for some assistance in addressing the worst that colonial oppression has resulted in.

But there are additional issues related to the land claims process. These land claims processes take 25 to 30 years to complete where there is little inherent that serves the most vulnerable due to colonial structures such as women and children. In short the process is not rooted in gender parity where qualified women are given the much needed opportunities.

What is more, while in the Algonquin land claims process in Ontario there is a hunting interim agreement, there are no interim policies directly for women and children such as food banks, head start programs, or shelters. Further, although there are 17 provincial parks in Ontario no employment opportunities are designated solely for Indigenous women and students. Improving the lives of women and their children in concrete and practical ways is the best way to prevent poverty, health issues such as disabilities, and sexual oppression such as incest, rape, and prostitution.

As I discuss the Algonquin land claims process I need to stress here that its limitations do not only reside with Canada’s policy and process. Of course the issues of sexism and patriarchy are manifesting in real ways at the level of practice in our communities. Realities such as internalized oppression, lateral violence, the use of confounding rhetoric much like Canada does with their Indian policies and laws, and token appointments are rampant where as a result women and children’s needs continue to be denied and they are harmed further. This is the nature of oppression; the most vulnerable suffer the most.

In your mandate letter PM Trudeau outlined several top priorities such as:

- To support the work of reconciliation, and continue the necessary process of truth telling and healing, work with provinces and territories, and with First Nations, the Métis Nation, and Inuit, to implement recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, starting with the implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

As an Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe it is important that I take the time and stress to you as the Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs that when considering whom the First Nation members consist of you will need to value that there are both status and non-status Indigenous people. To assure clarity I need to stress two matters here.

First, through the Indian Act Canada has created more non-status Indigenous people who are not tied to a particular federally recognized First Nation. For example in Ontario there are more than 6000 non-status Algonquin and approximately 1700 status Algonquin. My point is that as you carry out your mandate and top priorities, if you remain with addressing only the federally recognized First Nations and only with the federally recognized status Indians, this will leave out the needs of many Indigenous people and voices. As you carry out your mandate please ensure you recognize in concrete ways the broader realities of who Indigenous people are. Said another way, only listening to the voices of federally recognized Chiefs of First Nations and/or the people who currently sit at what are better known as “termination tables” is too narrow.

Second, it is important to value that the larger non-status Indigenous people are not members of the Métis Nation, neither culturally or politically. Being a non-status person does not make one a Métis by default. The Métis Nation defines its own membership.

In the tradition of truth telling it must be appreciated that Canada’s parliament buildings reside on Algonquin Anishinaabeg territory and that Canada’s truth begins at home on Algonquin land.

Miigwetch,

Lynn Gehl, Ph.D

Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe

Comments

Be the first to comment