Unpublished Opinions

Founder and President of democracy think-tank, Section 1, Senior Fellow of Massey College, Centre Associate of the UBC Centre for Constitutional Law and Legal Studies, Canadian International Council Advisory Board Member, Chair Emeritus of the Jane Goodall Institute, and editor, most recently, of The Notwithstanding Clause and the Canadian Charter (McGill-Queen`s University Press)

Section 33 has no place in a liberal democracy. It ought to be repealed: The notwithstanding clause is a dangerous and altogether unnecessary tool

Two premeiers, Doug Ford and Francois Legault, have resorted to the Notwithstanding clause within a month of each other. Section 33 has no place in a liberal constiutional democracy. It ought to be repealed

The notwithstanding clause is a dangerous and altogether unnecessary tool

Peter L. Biro: Section 33 has no place in a liberal democracy. It ought to be repealed

The notwithstanding clause is a dangerous and altogether unnecessary tool

Peter L. Biro, Special to National Post

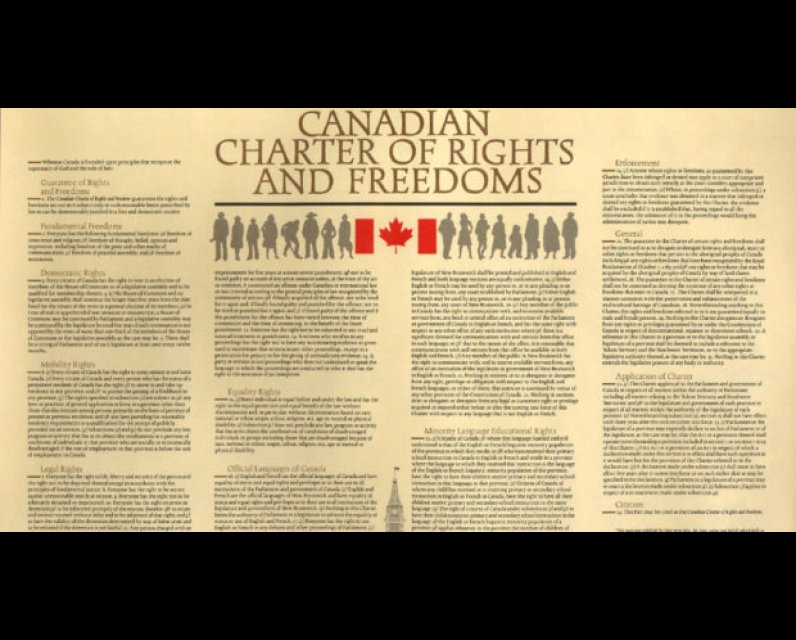

Publishing date: Jun 15, 2021 The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Photo by The Canadian Press

Canada’s democracy has always been considered resilient and well immunized against the democratic backsliding that is occurring in other liberal democracies. Yet there is one feature of Canada’s Constitution that undermines this rather smug assessment: Section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms — the infamous notwithstanding clause — which permits Parliament and the provincial legislatures to provisionally suspend the operation of the charter with respect to certain fundamental rights and freedoms.

In recent weeks, we have seen two provincial premiers resort to the notwithstanding clause in order to insulate legislation from charter scrutiny. In Ontario, Premier Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative government announced that it plans to invoke the notwithstanding clause in order to restore parts of the Protecting Ontario Elections Act that restricts third-party election advertising and that had been struck down by a judge for infringing freedom of expression.

Ford’s risky move, Kenney’s woes and the collapsing Greens | Ep13

And in Quebec, the Coalition Avenir Québec government of Premier François Legault has invoked the notwithstanding clause as part of Bill 96, which seeks to amend Canada’s Constitution to identify Quebec as a nation and make French its official and common language. In 2019, the Legault government also resorted to the notwithstanding clause when it passed Bill 21, An Act Respecting the Laicity of the State, which is intended to eradicate religious symbols in most of the public sector.

Back in 2018, Premier Ford introduced legislation cutting the size of Toronto’s city council in half, and announced that he would be prepared to invoke Section 33 in order to save the law in the event that it was found to violate the charter. In the face of public opposition, both Ford and his attorney general cavalierly defended the proposed use of Section 33 by touting their access to “all the tools in the toolbox.”

The willingness of our leaders to resort to the notwithstanding clause is cause for concern. Although the invocation of Section 33 does not offend the rule of law because the notwithstanding clause is, indeed, in the constitutional “toolbox,” it nevertheless poisons the liberal-democratic well from which free citizens draw their water.

Section 1 of the charter already anticipates that there will be circumstances in which rights and freedoms may lawfully be curtailed. But the courts have imposed a rigorous, multi-pronged test under Section 1 that requires the government to establish that the law or action responds to a matter of pressing and substantial concern, that its objective is rationally connected to the abridgement of a charter right, that the impairment of the right must be minimal and that there must be proportionality between the benefits of the law and the deleterious effects of the impairment.

With Section 33, however, governments are not required to satisfy a judge that any of these conditions are present. Except to the extent that a government’s purpose is articulated in legislative debate, the exercise of justifying the abridgement of constitutionally protected rights and freedoms can be dispensed with altogether when such an exercise risks producing an inconvenient or embarrassing result for the government.

The notwithstanding clause is the product of some heavy-handed, high-stakes bargaining amongst federal and provincial negotiators during the constitutional negotiations of 1981. The insistence by then-premiers Peter Lougheed, Allan Blakeney and Sterling Lyon on the inclusion of such a constitutional override clause was crucial in securing the requisite provincial support for the patriation package.

The principal justification for such an override was perhaps best articulated by constitutional law scholar Peter Russell: “A belief that there should be a parliamentary check on a fallible judiciary’s decisions on the metes and bounds of our fundamental rights and freedoms.” However, almost four decades after the inclusion of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in Canada’s Constitution, we have had the benefit of a rich and well-developed jurisprudence under Section 1.

It is high time we recognize that the escape hatch of Section 33 undermines Canada’s commitment to protecting civil liberties, erodes the legitimacy of our democracy, renders it vulnerable to democratic backsliding and compromises Canada’s credentials as a global champion of human rights and liberal-democratic values.

The problem is not that first ministers will be tempted to use all the tools in the constitutional “toolbox,” but that Section 33 is a dangerous and altogether unnecessary tool. It simply has no place in the constitutional toolbox of any mature and robust liberal democracy. It ought to be repealed.

National Post

Peter L. Biro is the founder of Section1.ca, a democracy and civics education advocacy organization, a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts and chair emeritus of the Jane Goodall Institute, Global. He is a lawyer, business executive and the editor of “Constitutional Democracy Under Stress: A Time For Heroic Citizenship.”

Comments

Be the first to comment