Stay informed

Is It Dangerous to Let Kids Be Free?

.main_housing p > a { text-decoration: underline !important; }

.th-hero-container.hm-post-style-6 { display: none !important; }

.text-block-underneath { color: #333; text-align: center; left: 0; right: 0; max-width: 874.75px; display: block; margin: 0 auto; } .text-block-underneath h4{ font-family: "GT Sectra"; font-size: 3rem; line-height: 3.5rem; } .text-block-underneath h2{ font-size: 0.88rem; font-weight: 900; font-family: "Source Sans Pro"; } .text-block-underneath p { text-transform: uppercase; } .text-block-underneath h3{ font-family: "Source Sans Pro"!important; font-size: 1.1875rem; font-weight: 100!important; }

.flourish-embed { width: 100%; max-width: 1292.16ppx; }

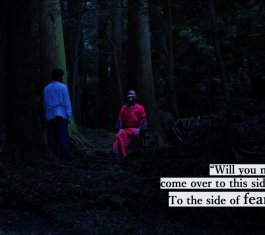

.th-content-centered .hm-header-content, #primary.content-area { width: auto; } .entry-content p, ul.related, .widget_sexy_author_bio_widget, .widget_text.widget_custom_html.widget-shortcode.area-arbitrary { margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto; } .hitmag-full-width.th-no-sidebar #custom_html-45.widget { margin: auto; } @media only screen and (max-width: 768px) { .img-two-across-column{ flex-direction: column; } .img-two-across-imgs{ width: auto !important; max-width: 100%!important; padding:0px!important; } .main_housing, .text-block-underneath { margin-left: 25px !important; margin-right: 25px !important; } .text-block-underneath h4{ font-family: "GT Sectra"; font-size: 35.2px; line-height: 38.7167px; } } @media only screen and (min-width: 2100px) { .main_housing, .text-block-underneath { /* margin-left: 32% !important; margin-right: 32% !important; */ } } @media only screen and (max-width: 1200px) { .main_housing, .text-block-underneath { /* margin-left: 25px !important; margin-right: 25px !important; */ } } @media only screen and (max-width: 675px) { .main_housing, .text-block-underneath { margin-left: 10% !important; margin-right: 10% !important; } } .hero-tall {display: none;} .hero-wide { display: block; } @media (max-width:700px) { .hero-wide { display: none; } .hero-tall { display: block; } } SOCIETY / MARCH/APRIL 2026 Is It Dangerous to Let Kids Be Free? From bus rides to playgrounds, we are raising our children in a culture of fear BY SIMON LEWSEN ILLUSTRATION BY ANSON CHAN

Published 6:30, JANUARY 26, 2026

ADRIAN CROOK, a father of five from Vancouver, has always known what danger looks like: it’s a boxy stamped-metal contraption, with four wheels, a transmission, and a hood. When Crook was a teenager in the ’90s, his high school friend Sheri was killed in a car crash. She was coming back from a party with three friends when the driver lost his bearings and wrapped the vehicle around a pole. Over a decade later, in 2006, Crook’s grandmother was walking home from a shopping mall in Burnaby, British Columbia, when a truck ran her over at a crosswalk. She went into a coma and died in hospital.

Crook’s first son was born two months after that accident. From that moment, Crook carried the certainty that if the boy met an early death, it would almost certainly involve a car. This was a simple matter of statistical probability. In Canada, vehicular accidents are, by far, the leading killer of children and teens.

Crook and his wife had four more kids, before separating in 2013. She found a house in North Vancouver, and Crook, who hated suburbia, rented a three-bedroom condo across the inlet in downtown Vancouver. As a freelance videogame designer, he made his own hours and, in his spare time, threw himself into projects for his children. He commissioned a custom dining table large enough to seat all five kids plus their friends, and he converted his condo storage room into an art space. Often, he’d dress his kids in matching pinnies so he could see them easily, then take them out for a downtown adventure—a play session at a jungle gym, a walk by False Creek, or, on special occasions, a trip to a local diner, which served deep fried Mars bars.

Crook owned a car but avoided driving: he views it as expensive, dirty, and dangerous. To get around, he and his children relied on transit, which worked fine for summers and weekends. The problem was weekdays, when his four oldest kids went to school near their mother’s home. For the first two years, he drove them. Then he stopped—unwilling to keep relying on a car—and began riding with them on the bus, a forty-five-minute haul across two routes. Crook made the trip morning and afternoon. “It took a three-hour bite out of my day,” he says.

To him, accompanying his children seemed pointless. The kids, by then aged six to ten, were consummate transit users. They were on a first-name basis with the bus drivers and knew the routes so well they could do them blindfolded. Plus, they travelled in a pack, with cellphones that tracked their movements. Did Crook really need to be there?

In early 2017, he decided to opt out. He gave his kids lessons on transit safety and did a few trial runs, with him sitting at the back of the bus, silently observing them. Then he let them do the trip on their own. They returned from school triumphant. Crook was elated too. “Kids feel empowered when they get to navigate the world,” he says. At last, he had his workdays back.

His victory was short lived. In the spring of 2017, Crook got a call from a social worker with BC’s Ministry of Children and Family Development. Somebody had spotted his kids on the bus and notified the department, triggering an investigation. The ministry’s view was that children under ten should be watched by someone at least twelve years old. In late April, Crook sat down in his living room with a government-appointed social worker, who assailed him with questions: Why wasn’t he with his kids? Couldn’t he drive them to school? Did he really think a seven-year-old was safe riding the bus without an adult?

The social worker visited the kids at school and interviewed each of them. She and a colleague also continued to speak with Crook. He says he asked them for specifics about the supposed dangers his children faced. Their answers struck him as either preposterous (Was it even possible, he wondered, for a kidnapper to whisk one of his kids away without the others raising a hue and cry?) or banal (If a bus was delayed and his children were forced to wait at a street corner, so what?).

To defend himself, Crook appealed to data. He cited a 2013 study that analyzed crash risks according to mode of travel and showed, overwhelmingly, that bus passengers are the safest travellers on the road. (More recent research has bolstered this conclusion, including a 2018 study that examined the ten Montreal bus routes with the greatest number of injuries and found that the risk of injury for car occupants was nearly four times higher than for bus passengers). Riding a bus, in other words, is far safer than travelling by car. The ministry, Crook argued, was asking him to increase his children’s risk exposure. And they were doing it in the name of safety.

The conversations, he says, went nowhere. When Crook spoke statistics, the social workers spoke vibes. Didn’t he just know his kids were too young to be left alone? In desperation, Crook asked the query that weighed heaviest on his mind: Had he done anything illegal? A social worker explained that questions of legality weren’t the only issues at stake. The ministry was enforcing a guideline, not an actual law—but in practice, that distinction seemed to make little difference. To Crook, the message was clear: We don’t necessarily think you’re a criminal. But we still might think you’re a lousy dad.

WHEN I BECAME a parent, over three years ago, I found myself asking questions similar to the ones Crook wrestled with—about danger and reward, independence and safety. What risks, I asked, would I let my daughter take? What parenting norms would I break? And what would other people think of me?

As an elementary school kid in the ’90s, I lived much of my life away from the gaze of hovering parents. My best friend and I would walk to and from school together. On weekends, we’d bike around our suburban Toronto neighbourhood. We’d search for abandoned properties to explore or bring shovels to the nearby ravine to dig for God knows what—buried treasure, I guess, or bodies. In my friend’s basement, we’d grind charcoal, then mix it with sulphur and potassium nitrate to make gunpowder, which we’d stuff into homemade fireworks. Our world felt rich and mysterious. We saw ourselves as swashbuckling adventurers, not the prepubescent rugrats we so clearly were.

As the world has come to seem scarier, the tech industry has found ingenious ways to draw kids indoors, and offline spaces have emptied.

The culture has changed, and our perception of danger has too, because we know so much more about it. Schoolyard bullying, we now see, can do real emotional damage—much as concussions, which we once brushed off as minor, can have lasting neurological effects. We no longer see kids on milk cartons, but we get loud, piercing Amber alerts by phone, reminding us, at any hour, that another child is missing. As the world has come to seem scarier, the tech industry has found ingenious ways to draw kids indoors: iPad games that are micro-targeted to every age level, YouTube channels with unlimited slop. And so the offline spaces where kids once congregated have emptied out.

In her new book, 10 Rules for Raising Kids in a High-Tech World, Jean M. Twenge—a leading US psychologist studying generational change—catalogues the differences between childhood today versus childhood four decades ago. “While 10-year-olds once had the free range of their neighborhoods, many kids these days are not allowed to go anywhere by themselves,” she writes. She later adds, “While 13 was once considered old enough to be a babysitter, many now think 13-year-olds need a babysitter.”

Twenge’s description resonates. In the residential Ottawa neighbourhood where I now live, I rarely see kids playing pick-up sports or roaming the streets in packs. The adventure playgrounds of the ’70s—with their hammers, nails, and planks of wood—have been replaced by prefabricated climbing structures with catalogue-ordered parts. In Ottawa, these contraptions have notices on them telling parents to supervise their children’s play. The parents obey, following a foot behind their kids and issuing instructions in that cloying voice adults use for babies and animals.

Is any of this healthy? When my daughter was born, I promised myself I’d do things differently. Together, she and I constantly search out new spaces to explore—ravines, splash pads, brew pubs with big outdoor patios. I let her wander as far as she wants to, so long as she doesn’t go near roads or escape my peripheral vision.

Frequently, my daughter and I travel to Toronto by train. I refuse to anesthetize her with a screen for the entire ride. Instead, she runs up and down the aisles, climbs into the baggage compartments, and has imaginary tea parties with her stuffed animals on the vacant seats. On winter days in Ottawa, we go to the National Arts Centre, which often leaves its lobby and mezzanine open to the public. One time, we broke into the empty theatre, likely because custodial staff had neglected to lock the door. I watched my daughter roam the hall, her journey illuminated by a ghost light on the proscenium stage.

My hands-off approach to parenting gets mixed reactions from other parents. Some praise me. Some are fascinated by my toddler, who strides through public spaces, arms swinging confidently. Others are appalled. In the fall of 2024, my daughter fell from a climbing structure. I was reading on a nearby bench and didn’t realize that the crying I heard was coming from her. After about thirty seconds, I looked up, saw what had happened, and came running. My daughter calmed down in my arms, but another parent at the park was furious with me.

She told me to take my daughter to the ER and request a cognitive assessment for brain injury. I ventured that the accident had been minor, since the ledge from which my daughter had tumbled was a mere foot and a half above the ground. The woman said that I was in no position to judge the fall since I hadn’t actually seen it. “We have different parenting styles,” I offered, trying to defuse her anger. “This isn’t about parenting styles,” she shot back. “This is about neglect.”

Like many journalists, I have a thick skin, but this stranger’s words destroyed me. For a week, I walked around in a funk, wondering if she’d seen something in me that I’d failed to see in myself. In the future, when I ran into her at the park, I stood close to my daughter, performing attentiveness. I feared another blow-up or a call from child services.

A year has passed since then, and I can now more clearly see the obstacles to my preferred style of parenting. Even peers who agree with me are hesitant to do things my way, because they dread the social and emotional costs. If you’re a “free-range” parent—someone who gives their kids room for independence and autonomy—you’re going to get chastised by random busybodies. When that happens, a voice inside you will ask, What if the busybodies are right? Danger, after all, is real. And on the other side of danger? Unimaginable loss. Who on Earth wants that?

IF I COULD DETACH from emotions and focus on data, I’d probably feel less internally conflicted about my approach to parenting. As I understand it, the science has my back. Today, across the world, researchers in education, pediatric health, and developmental psychology are making the strongest case yet for childhood independence and risk. Some entered the field in the 1990s and 2000s, when safety culture was coming into vogue and their ideas were pushed to the margins. They are now part of the establishment: the agenda setters, the influential thinkers, the voices shaping their fields. They’re trying to shift norms in the larger world too.

Research reveals that children allowed to wander alone play longer, burn more energy, and build richer social lives.

Why might safety culture harm young people? One answer is that it suppresses spontaneity. Chaperoned kids are less likely to do things they probably should be doing. Research from University College London reveals that children allowed to wander alone play longer, burn more energy, and build richer social lives than “sedentary, house-bound peers.” Researchers at the University of Bristol found that ten- and eleven-year-olds trusted with wider roaming rights were vastly more active, especially on school days, than those kept close to home—shrinking freedom, it seems, helps explain shrinking fitness. In 2010, researchers in Sydney, Australia, outfitted the playgrounds at twelve local schools with car tires, milk crates, and weighted boxes. These objects created mild dangers—they could be dropped, thrown, or stacked into rickety climbing structures—but they also got students moving: physical activity levels increased by 12 percent.

The benefits of free play go beyond friendship and exercise. One might view childhood as a kind of rehearsal for adulthood. By this reasoning, when adults intervene unnecessarily in children’s lives—supervising their play, mediating their disputes—they effectively call the rehearsal off, increasing the odds that things will go poorly later on.

Even the school playground may be a site where adult life skills are formed. In a forthcoming study, Mariana Brussoni, a health scientist at the University of British Columbia, found that kids more prone to engage in risky scenarios—that is, thrilling and exciting forms of play, with a real chance of injury—were better at navigating a virtual-reality road-crossing game than their peers. They made faster decisions about when to cross, with fewer near accidents. Low-stakes risk taking on the playground, Brussoni theorizes, may help build up the instincts and intuitions needed to avoid serious injury throughout our lives.

Of course, childhood isn’t only about skills acquisition. It’s about developing cognitive capacity and mental resilience too. This is where the benefits of independent play may be most powerfully felt. It’s a near consensus among researchers that, when young people are given space to manage conflicts independently, they build up an arsenal of cognitive aptitudes—empathy, tolerance, self-reliance.

Relatedly, a study out of the University of Colorado Boulder and the University of Denver shows that children who engage in unstructured activities tend to have better executive functioning—a suite of cognitive skills that includes planning, self-control, and flexibility—relative to children whose time is regimented and monitored. Good executive functioning, moreover, contributes positively to a variety of life outcomes, from higher earning potential to greater longevity.

Some of the most promising new research is in the area of childhood independence and mental health. In the mid-2010s, Helen Dodd, a child psychologist at the University of Exeter, was watching her own children play when she had a novel thought: Isn’t play basically a form of exposure therapy? For around two decades, Dodd has helped young people with extreme anxiety. Treatment often involves some form of therapy whereby the patient goes out and does the very thing they’re afraid of doing. A young person with social phobia, for instance, might go to a party or strike up a conversation with a stranger. The logic is simple: you conquer fears by facing them.

Dodd realized that a rich play environment—at least when it’s not overregulated by hovering adults—is a terrain of risk: failure, injury, social rejection. Perhaps we seek out risky play as kids because it familiarizes us with uncertainty and also with our capacity for adaptation. “If parents just got out of the way during playtime,” Dodd reasoned, “children might learn to handle anxiety on their own.”

She has since reoriented her research to focus on this theory. She surveys parents of children aged two to eleven—and, where age appropriate, the children too. Drawing on established research protocols, she asks questions like: How many tantrums does your kid have per week? How long are the tantrums? Does your child have prolonged periods of extreme isolation or withdrawal? Are they anxious about doing things that other children consider fun? The results suggest that young people who engage in risky play are less likely to exhibit signs of anxiety or depression. Dodd is now working on a randomized control trial, in which four schools will embrace risky play and four will not. “Resilience,” she theorizes, “is a muscle to be trained.”

This line of thinking requires us all to reframe our understanding of childhood risk—to see it as both a hazard and an opportunity. When she was coming up in the ’90s, Brussoni, the UBC professor, found herself out of step with her peers. The field of pediatric public health came to be dominated by epidemiologists who noted that the primary cause of childhood injury was falls from playground equipment. The trend was reinforced by ER physicians who were routinely treating children with serious injuries. When you’ve witnessed trauma like that, you naturally want to eradicate it from the world. Still, Brussoni thought that this goal was untenable—and harmful too.

She favours a more evidence-based, expansive understanding of risk. Car accidents, suicides, and opioid use are among the leading causes of death for kids. But other hazards take up more room in our imaginations. Pregnancies, violence, criminal delinquency—these phenomena are vastly less prevalent among teens and tweens than they were a generation ago, perhaps because of lower levels of lead poisoning and its behavioural effects, decreasing rates of child sexual abuse, and the widespread availability of contraception.

In BC, where Brussoni lives, only 241 of the province’s roughly 700,000 children, on average, were hospitalized annually for playground injuries between 2002 and 2023. The vast majority of these injuries were broken bones. In the twenty-first century so far, says Brussoni, the available data suggests only two children across the country have died from such accidents. Stranger abduction, meanwhile, is so rare its probability is estimated at one in 14 million. In cases of abduction, the culprit is almost always a person the child already knows. And those Amber alerts on our phones? The vast majority of missing children reports are the result of young people running away.

Is it heartless to say that the rates of playground deaths and street abductions are already as low as we might reasonably want them to be? It’s probably also true. “I’m a population-health researcher, so I look at the big picture,” says Brussoni. “I’m not looking at any one kid with exceptionally tragic circumstances, although I have great sympathy for that kid and their parents.” An anomalous tragedy is just that—a tragedy. And an anomaly. Sound health policy isn’t based in random statistical outliers. Neither is sound parenting.

IT’S ONE THING to agree with this argument; it’s another to live by it. People adjusting to the idea of free-range parenting can struggle, as I do, with fear and self-doubt. To get over it, they seek new ways of thinking.

Heidi Bergstrom, an accountant and parent of three in Camrose, Alberta, became a proponent of risky play after her husband, Gregory Doll, a phys-ed teacher, attended a conference session on the subject. Bergstrom is risk averse by nature, but she keeps her protective instincts in check. In summer, she and Doll allow their two oldest, aged eight and six, to explore a nearby walking path independently while staying within a one-kilometre radius. The kids are well versed in road safety and travel with walkie-talkies, which sometimes go out of range.

Bergstrom doesn’t know exactly what they get up to on their rambles, but she says that they always return energized and elated. “Of course, the whole thing makes me nervous,” she admits. “But I remind myself that, by letting them have autonomy now, I’m protecting their future selves.”

In moments when parental anxiety threatens to overwhelm her, Bergstrom thinks back to her most joyous childhood memories—the afternoons spent jumping into haybales, wading in ponds, or setting off down a slough on makeshift rafts assembled from junk. “I was happiest,” she says, “when I was outside with friends, without adults around. My children need to make similar memories.”

Lauren Jane Heller, an executive coach and mother of two, had, in some ways, a less idyllic childhood than Bergstrom’s. She was born in South Africa, where she spent part of her formative childhood years, along with extended stints in Toronto. In Cape Town, where she and her family lived in the ’90s, muggings at gunpoint were rampant. The homicide rate was higher than in most other places on Earth. Heller’s grandmother was murdered in a violent home invasion.

When Heller was fourteen, her family returned to Canada, and she was struck by the similarities and differences between her two homes. Montreal, where Heller eventually settled, was a thousand times safer than Cape Town, yet people still talked as if danger lurked around every corner. If a child was abducted and killed anywhere in the country, the incident would dominate the news cycle for months. “I remember thinking, Isn’t it amazing that Canadians can afford to freak out about one kid?” says Heller.

As a new mother in the early 2010s, Heller lived with her husband in Pointe-Saint-Charles, a gentrifying neighbourhood southwest of downtown Montreal. She tried to conform to the vigilant parenting norms of her Canadian community, but these practices frustrated her. “I remember sitting in the park watching my kids play,” she says. “I kept thinking, This is so dumb. Why do I have to be here?”

In 2015, the family moved to a new home one block from the old one. Across the street was a couple with four kids and a parenting ethos similar to Heller’s. Soon, her kids, aged six and three, were roaming the neighbourhood with the children from across the road, aged eleven, nine, seven, and five. “The older two girls were sweet and helpful, and they loved my kids,” says Heller. “I trusted them. We live in a densely populated community. If anything went wrong, they’d find an adult to help out.”

Today, Heller’s children, both teenagers, take the metro to school—and to hang with friends, who live all over the city. “They’ve been asked for drugs,” says Heller. “They know what used condoms look like. But they’ve surely seen worse things on TV.”

If there’s anything unusual about her children’s upbringing, she argues, it’s the degree of security they enjoy. “One of my kids is trans, and the other is thirteen but dresses like a twenty-year-old punk rocker,” says Heller. “And yet they feel secure. Isn’t this evidence that we’re succeeding as a society?” Heller believes that safety, like all forms of privilege, goes unacknowledged and unappreciated by those who possess it.

That doesn’t mean she never worries. Every free-range parent I spoke to for this piece told me—albeit not in so many words—that they manage their safety concerns by invoking that old adage about changing the things you can’t accept and accepting the things you can’t change. Risk is an essential part of life, they reason, but you can still distinguish between necessary and excessive kinds.

Jeni Marinucci, a writer and editor from Milton, Ontario, remembers when her youngest child first discovered the power of fire. The family was on a camping trip when, one morning, she felt warmth at her back. She turned around to see her four-year-old son standing over a fire and smiling with Promethean glee. With a stick, he’d dug up glowing embers from the evening before, then stoked them with leaves and twigs.

How should she respond? One option was to scold her son, then vow to keep a closer eye on him going forward. But an interest in fire, she reasoned, is linked to a broader sense of curiosity about the world. Isn’t that a virtue? “We need fire when camping,” she told her son. “Do you want to be the fire chief? If so, you also need to be the fire safety chief.”

The distinction between risk and recklessness is sacred. But there’s no fail-safe way to ensure you’re on the right side of that line.

She bought him protective gloves, goggles, tongs—even, eventually, a Zippo lighter—and taught him everything she knew about fire management. In an era when young men are disappearing into bedrooms and internet forums, her son remains fascinated by the tactile, physical environment. When he was eleven, he built a homemade kiln to fire clay he’d dug up in the backyard. Now, he’s twenty-one and a trained blacksmith, volunteering at a real-life smithy run by a local historical society.

For Marinucci and other free-range parents, the distinction between risk and recklessness is sacred. You embrace the former and avoid the latter. But as everyone knows, there’s no fail-safe way to ensure you’re always on the right side of that line. And so you trust your instincts and make peace with an uncomfortable fact: things can go horribly wrong, even if they likely won’t.

Nathan Whitlock, a parent of three in Hamilton, Ontario (and a contributor to The Walrus), remembers the time he climbed a waterfall on the Niagara Escarpment with his preteen daughter. For half an hour, they scrambled along mossy rocks, grabbing hands for stability, until, suddenly, they were looking out at the world from forty feet up. The memory is one of Whitlock’s favourites. But the adventure didn’t have to turn out so well. “I remember thinking, What if she slips and falls?” Whitlock says. “This is either the best parenting decision of my life or the worst one.”

THE WORK OF PARENTING, as I understand it, is not to shield kids from risk but rather to help them navigate a world of countervailing risks. The dangers of free play—injuries, bullying, peer pressure, substance abuse, the possibility of getting lost or mugged while roaming the neighbourhood—are real. But they’re offset by other dangers: depression, anxiety, isolation, the negative cardiovascular effects of a sedentary lifestyle, and the developmental costs that come from a lack of familiarity with danger. Parenthood is an unwinnable game. We’ll be better at it if we accept this fact.

I wish our culture did more to support free-range parents. Recently, we’ve taken modest steps in that direction. In early 2024, the Canadian Paediatric Society set out its position on risky play, which encouraged “thrilling and exciting forms of free play that involve uncertainty of outcome and a possibility of physical injury.” Newly opened playgrounds, from Vancouver’s Charleson Park, with its pirate ship decked out in climbing nets, to Toronto’s Biidaasige, with its ziplines and water pumps, hark back to the ’70s, the golden era of children’s play. We need more of that.

In 2018, the state of Utah passed North America’s first free-range parenting law. The bill clarifies that child protection agents cannot investigate parents merely for allowing kids to walk, play, or wait in a car unsupervised. As of summer 2025, ten other states have passed similar bills. In Canada, we could do the same. At the very least, we could put more government resources into making Stay Safe—a safety-training program devised by the Canadian Red Cross and targeted to kids—widely available. In doing so, we’d shift the burden of child safety, ever so slightly, from adults to children, who are capable of doing some of this work themselves.

Ultimately, though, a change in parenting practices must come from parents. This means reckoning with the psychological barriers that prevent us from giving our children the space they need to play and grow—barriers that are, perhaps, more complicated than I originally thought they were. Yes, a fear of abduction or injury is holding parents back, but so too is another, more deep-seated, anxiety.

Last September, I was at the National Arts Centre again with my daughter, when I realized I had to pee. “Come to the bathroom,” I told her. She responded, as usual, with an authoritative no. “You go peepee,” she told me. “I stay here.” I didn’t feel like fighting. So I left her for two minutes, believing that she’d be fine.

When we follow kids at the playground and accompany them at job interviews, we shore up our centrality in their lives. We do it for us, not them.

The next morning, I nevertheless felt weird about my decision, not because things had gone badly but rather because they’d gone well: my daughter had enjoyed two minutes of complete autonomy in the middle of a bustling city. It was a victory that presaged greater victories to come—and greater losses too. Someday, she’d be able to spend hours or even days on her own. Those two minutes of freedom were the beginning of a gradual process of separation, exhilarating for her, devastating for me.

Helicopter parenting isn’t only about risk aversion. When we overprotect our kids—when we follow them at the playground, chaperone them on social outings, and accompany them at job interviews—we shore up our centrality to their lives. This tendency may feel benevolent, but it’s probably damaging. And let’s not lie to ourselves: we do it for us, not them.

After a nearly two-month investigation, the Ministry of Children and Family Development found that Crook’s children were unsafe on transit, noting, as well, that Crook’s ex-wife did not approve of his kids travelling to school on their own. (Unlike Crook, I’ve been lucky, as a free-range parent, to have the complete support of my co-parent and extended family.) The ministry set new rules for Crook: he was now forbidden from letting his younger kids out of sight for any amount of time until they turned ten. To comply with the order, Crook mostly kept his children indoors. He resumed the daily commutes to and from school.

He also petitioned the ministry to review the order. They left it in place, as eventually did the Supreme Court of British Columbia. It would take three years—and roughly $70,000 in legal fees, most of it crowdfunded—for Crook to finally have the decision reversed. That happened in 2020, when the Court of Appeal for British Columbia determined that the ministry had overstepped its mandate.

In a sense, Crook had beaten the charge of being a lousy dad. But what was his reward? The same painful outcome that parents who raise healthy, independent kids all eventually face. Crook’s oldest son recently left the Army Cadets, which had him living on bases across the country, and is starting post-secondary studies. His oldest daughter is studying media at university. His middle and youngest children, both boys, are gym rats and rugby players; they live with their mother, close to school. Crook’s youngest daughter, a budding athlete and student council rep, still lives with him, but her calendar is jammed with social and extracurricular activities.

In short, everything worked out fine. In a world in which many kids are homebound, lonely, and struggling to launch, Crook has helped raise five confident children with rich, autonomous lives. The upshot, for him, is a rapidly emptying nest. His children call when they can, but they have other priorities on their minds and other relationships to manage. “I sometimes get sad,” says Crook. “But parenting is about making your kids not need you.”

The post Is It Dangerous to Let Kids Be Free? first appeared on The Walrus.

Comments

Be the first to comment