Unpublished Opinions

smiths falls, Ontario

About the author

Advocates for family preservation against unwarranted intervention by government funded non profit agencies and is a growing union for families and other advocates speaking out against the children's aid society's funding strategies and current corrupt practices to achieve the society's funding goals.

More needs to be done to protect kids to keep them out of the Ontario’s unaccountable and secretive child welfare system.

November 2, 2019

More needs to be done to protect kids from child poaching funding predators to keep them out of the Ontario’s unaccountable and secretive child welfare system.

Corporatism: Fascism's theory of economic corporatism involved management of sectors of the economy by government or privately-controlled organizations (corporations). Each trade union or employer corporation would theoretically represent its professional concerns, especially by negotiation of labor contracts and the like.

Marketization of law making is a process that enables the elites to operate as market oriented firms by changing the legal environment in which they operate in, in the best interest of the child according to a bunch of sociopathic child poaching funding predators...

One of the 14 characteristics of fascism is -

Corporate Power is Protected.

The industrial and business aristocracy of a fascist nation often are the ones who put the government leaders into power, creating a mutually beneficial business/government relationship and power elite.

The people in fascist regimes are persuaded that human rights and procedural protections can be ignored in certain cases because of special need.

When the people who have power in our society can have an influence in law making, the laws that get created will not maintain the appearance of equality and the elites in society can lobby and eventually criminalize the poor.

The laws will start to benefit the big corporations (elites). This is well illustrated in Stan Cohen’s concept of the moral panic. A moral panic refers to the reaction of a group within society (elite) to the activities of a non elite group. The targeted group is seen as a threat to society also referred to as the folk devil.

Here we can see here how child welfare law is not applied equally to everyone. In this particular instance the child welfare law is benefiting the people with means. The lawyers themselves.

Comack states; “While the pivotal point in the rule of law is ‘equality of all before the law’, the provision of formal equality in the legal sphere does not extend to the economic sphere. Thus, the law maintains only the appearance of equality because, it never calls into question the unequal and exploitative relationship between capital and labour.” This statement implies that the law is in place to be neutral. Therefore, the law would apply equally to everyone, including both the working and elite class. It can be said that in today’s society we have the marketization of law making.

:::

Harassment is a form of discrimination. It includes any unwanted behaviour that offends, humiliates, degrades or marginalizes you. Generally, harassment is a behaviour that persists over time. Serious one-time incidents can also sometimes be considered harassment.

CRIMINAL HARASSMENT

Are you worried about your family's security because an overzealous fanatic is:

■ using a lower corporate standard for reasonable grounds for continually launching or reopening investigations into your personal life hoping for a different result …

■ refuses to let you review your file for inaccurate information…

■ ignores or suppresses any information or documentation that indicates happy healthy children…

■ refuses you an opportunity to address concerns…

■ threatens to arbitrary remove your children if you don't allow them to search your home without a warrant or threatens court action to remove your children if you fail sign consent forms and service agreements…

■ interviews your children in school without recording the interview...

■ is contacting you over and over by phone, email and knocking at your door multiple times every day…

■ is watching your home or workplace…

■ is making you or your family feel threatened...

■ is peeking through your windows…

■ or attempts to talk your very young children into unlocking the door for them when they don't think your in the immediate vicinity...

You are experiencing criminal harassment and unless it's a CAS worker it’s a crime and you can get help...

:::

We all want to believe that nonprofit corporations like the children's aid society are full of hard-working people committed to improving society. But even the most well-meaning nonprofits can get into financial hot water.

Unfortunately the temptation to cover up financial problems can be particularly seductive for nonprofit CAS directors and board members when they're being sued foster home sex cults and unqualified group home staff drugging children out of their minds.

DEFINITION of 'Protected Cell Company (PCC)

The basic principle behind cell organization is simple: By dividing the greater organization into many multi-person groups and compartmentalizing and concealing information inside each cell as needed, the greater organization is more likely to survive unchanged if one of its components is compromised and as such, they are remarkably difficult to penetrate and hold accountable in the same way the mafia families, terrorist organizations and Ontario's children's aid societies are.

A corporate structure in which a single legal entity is comprised of a core and several cells that have separate assets and liabilities. The protected cell company, or PCC, has a similar design to a hub and spoke, with the central core organization linked to individual cells. Each cell is independent of each other and of the company’s core, but the entire unit is still a single legal entity.

BREAKING DOWN 'Protected Cell Company (PCC)

A protected cell company operates with two distinct groups: a single core company and an unlimited number of cells. It is governed by a single board of directors, which is responsible for the management of the PCC as a whole. Each cell is managed by a committee or similar group, with authority to the committee being granted by the PCC board of directors. A PCC files a single annual return to regulators, though business and operational plans of each cell may still require individual review and approval by regulators.

Cells within the PCC are formed under the authority of the board of directors, who are typically able to create new cells as business needs arise. The articles of incorporation provide the guidelines that the directors must follow.

The current hierarchical corporate structures that dominate our economies have been in place for over 200 years and were notably supported and defined by Max Weber during the 1800s. Even though Weber was considered a champion of bureaucracy, he understood and articulated the dangers of bureaucratic organisations as stifling, impersonal, formal, protectionist and a threat to individual freedom, equality and cultural vitality.

CAS actions are shrouded in secrecy, and media investigations are chilled by CAS (a multi-billion dollar private corporation) lawyers, who claim to be protecting the privacy rights of all involved to the exclusion of all other rights.

The GONE theory holds that Greed, Opportunity, Need and the Expectation of not being caught are what lay the groundwork for fraud. Greed and/or need provides the motive.

:::

“You know your system is based on the flimsiest of foundations when you have absolutely no standards on who can do this work,” adds Gharabaghi, director of Ryerson University’s school of child and youth care.

Regulation of child protection workers by Ontario College of Social Workers and Social Service Workers: CUPE responds.

"Mandatory registration and regulation by the College is not in the best interest of child protection workers and ultimately, not in the best interest of vulnerable children, youth and families."

HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT ONTARIO'S CHILD PROTECTION SOCIAL WORKERS TAKING OFF THEIR LANYARDS AND PUTTING ON THEIR UNION PINS TO FIGHT AGAINST PROFESSIONAL REGULATION?

-

Merton coined the term “self-fulfilling prophecy,” defining it as:

“A false definition of the situation evoking a new behavior which makes the originally false conception come true” (Merton, 1968, p. 477).

In other words, Merton noticed that sometimes a belief brings about consequences that cause reality to match the belief. Generally, those at the center of a self-fulfilling prophecy don’t understand that their beliefs caused the consequences they expected or feared—it’s often unintentional, unlike self-motivation or self-confidence.

-

In the psychology of human behavior, denialism is a person's choice to deny reality, as a way to avoid a psychologically uncomfortable truth like child protection in Ontario is a rogue agency gone mad with power.

There are those who engage in denialist tactics because they are protecting some "overvalued idea" which is critical to their identity. Since legitimate dialogue is not a valid option for those who are interested in protecting bigoted or unreasonable ideas from facts, their only recourse is to use these types of rhetorical tactics to give the appearance of argument and legitimate debate, when there is none.

-

The Slippery Slope: A slippery slope argument (SSA), in logic, critical thinking, political rhetoric, and caselaw, is a logical fallacy in which a party asserts that a relatively small first step leads to a chain of related events culminating in some significant (usually negative) effect.

Distinction without a Difference: A distinction without a difference is a type of logical fallacy where an author or speaker attempts to describe a distinction between two things where no discernible difference exists. It is particularly used when a word or phrase has connotations associated with it that one party to an argument prefers to avoid.

Either/Or Fallacy (also called "the Black-and-White Fallacy," "Excluded Middle," "False Dilemma," or "False Dichotomy"): This fallacy occurs when a writer builds an argument upon the assumption that there are only two choices or possible outcomes when actually there are several.

Red Herring: Attempting to redirect the argument to another issue to which the person doing the redirecting can better respond. While it is similar to the avoiding the issue fallacy, the red herring is a deliberate diversion of attention with the intention of trying to abandon the original argument.

False Dilemma Examples: False Dilemma is a fallacy based on an "either-or" type of argument. Two choices are presented, when more might exist, and the claim is made that one is false and one is true-or one is acceptable and the other is not. Often, there are other alternatives, or both choices might be false or true.

Circular Argument: In informal logic, circular reasoning is an argument that commits the logical fallacy of assuming what it is attempting to prove. ... "The fallacy of the petitio principii," says Madsen Pirie, "lies in its dependence on the unestablished conclusion.

:::

Regulation of child protection workers by Ontario College of Social Workers and Social Service Workers: CUPE responds: CONTINUED

I am aware that OACAS, the organization that represents my employer, is planning to make it mandatory for me to register with the Ontario College of Social Workers and Social Service

Workers in order for me to do my job.

One of the reasons given for introducing this requirement is that it will provide more oversight Children’s Aid Societies and child protection workers. Regulation through the College is entirely appropriate for social workers who are in private practice and whose work is not overseen by an employer. But I would like to remind [CAS] that my colleagues and I already answer to more than enough people, processes, and outside bodies in the course of our work, as the following list shows:

• CAS in-house management structure, including supervisors, managers, lawyers, and case conferences; (not public)

• a society’s internal standards, policies, procedures and protocols, some of which are governed by the Children and Family Services Act; (not public)

• a society’s internal disciplinary and complaints procedures; (not public)

• Office of the Provincial Advocate for Children and Youth, which has new powers to investigate CAS workers; (defunct)

• ministry audits in almost every area of service, including Crown Ward Reviews and Licensing; (see links below)

• Child and Family Services Review Board, which conducts reviews and hearings of complaints against a CAS worker; (by the ministry that funds them so there's no potential for conflicts of interests)

• family courts; (see links below)

• Ontario’s human rights tribunal; (see links below)

• the provincial auditor general; (see links below)

• child death reviews, including the Paediatric Death Review and internal reviews; (see links below)

• coroner’s inquests. (see links below)

How could anyone look at this list and possibly think that child protection workers need more oversight?

How about the long list of well publicized scandals ,tragedies, a one sided court system, fake experts, fake drug tests, sex cults and unexplained child deaths in care?

SEE LINKS BELOW

Asking for more ways to regulate and oversee the work of child protection workers is clearly unnecessary and leads me to think there is another agenda at work in this exercise.

I wanted to share some facts and figures that I have learned along the way; I think they point to significant problems for the sector and for [CAS] in particular:

Common sense is sound practical judgment concerning everyday matters, or a basic ability to perceive, understand, and judge that is shared by nearly all people. The first type of common sense, good sense, can be described as "the knack for seeing things as they are, and doing things as they ought to be done."

• There are over 5,000 child protection workers in Ontario

• The College regulates about 17,000 social workers and social service workers

• In Ontario, only 7% of College-registered social workers are employed by a CAS

• Only 4% of members of the Ontario Association of Social Workers work for a CAS

• Between 30% and 50% of Ontario’s child welfare workers do NOT hold a BSW

• Only 63% of direct service staff in CASs have a BSW or MSW (in 2012, it was 57%)

• Only 78% of direct service supervisors have a BSW or MSW (in 2012, it was 75.5%)

• The 2013 OACAS Human Resources survey estimates that ONLY 70% of relevant CAS job classifications would qualify for registration with the College leaving over 1000 unqualified workers shrouded in secrecy roaming loose in our communities.

• From 2002 to 2014, 41 child welfare employees who did not hold a BSW or MSW submitted equivalency applications to register as social workers; only 16 were successful and 25 were refused. (if that isn't a reason for concern - what is?)

Multidisciplinary child protection teams are a strength. Working alongside child protection workers who have taken a couple of years of education in psychology, sociology or mental health enriches the services they provide to children, youth and families, as well as the working environment we all share.

Similarly, those colleagues with backgrounds in such areas as children and youth justice offer insight and knowledge that would not normally form part of BSW or MSW. Sometimes a colleague has gained qualifications outside the country and brings unique cultural or community perspectives to our work.

What happens when those with backgrounds in youth justice start acting like they have BSW/MSW education in psychology, sociology or mental health?

Currently, workplace disciplines, complaints and other personnel matters at [CAS] are treated confidentially. But if child protection workers become subject to regulation by the College, previously confidential workplace matters will become matters of public record.

My membership in the College would mean that anyone can see information about my status or complaints made against me – and under the College’s rules, there is no time limit in which to make a complaint. Disciplinary hearings are open to the public and once a complaint is made, it is on file forever.

There is no process for appeal.

Employers must also file a written report with the College if one of its registered members is terminated. This requirement conflicts with an employee’s right to grieve a termination under the collective agreement or appeal it through arbitration, where a termination may be overturned.

I also have concerns for my personal safety and that of my family, since college registration is open to public scrutiny and provides no protection from potentially violent clients.

None of the ways that the College deals with personal information, complaints, and discipline allow for a fair or safe process for "child protection workers." (ad hominem)

There are any number of measures that can be and ought to be taken to restore public confidence in child protection and keep at-risk children and youth safer. Regulation by the college is not one of them.

I am not a social worker; I don’t want to be a social worker. Had I wanted to be a social worker, I would have trained as one.

If regulation through the College of Social Work is introduced, what will happen to us child protection workers who don’t have degrees in social work (a BSW or MSW) or a social service worker diploma? After all, we make up to 50% of the child protection workforce. (50%)

None of the options currently available to us is appealing: we can try to upgrade to the qualifications that will allow up to keep our jobs. We can move to a different job class. We can accept termination or layoff. (considering the job market what else aren't they qualified to do)

What doesn’t seem to be an option is “grandfathering,” something that would allow child protection workers already in post to keep doing their current jobs. The College is quite specific that grandfathering is not on the table. (so employees with decades of experience are off the table)

These facts seem to present some insurmountable problems for the child protection sector and represent another compelling reason that regulation by the College is a bad move for the child protection sector and for child protection workers.

One of the reasons given for this change is that regulation will result in higher quality services and bring greater professionalism to the field and that this will improve the standard of child protection work in Ontario.

I would like to point out that a failure to meet standards of care in child protection work is very rarely the result of professional misconduct, incompetence or incapacity on the part of individual child protection workers.

The stated purpose of the College is to protect the public from unqualified, incompetent or unfit practitioners.

But children’s aid societies already set those standards and ensure their adherence: they determine the job qualifications. They deal with employees they deem to be unqualified or

incompetent. And CASs decide whether child protection work in their area can be performed by someone who holds a Bachelor’s degree and has child welfare experience.

I may not hold a BSW or MSW degree, enjoy membership in the College or be subject to its regulation. But I feel like professional practitioner in the child protection sector and, as such, I cannot countenance this move toward the regulation of the child protection workforce. I am resolved to fight it at every step of the way and instead campaign for the measures that will bring real benefits to at-risk youth, children and families.

• Regulation with the Ontario College of Social Workers and Social Service Workers is entirely inappropriate for workers subject to employer oversight

• CAS employees are already subject to adequate oversight at several levels

• Without degrees in social work (BSWs or MSWs), many CAS child protection workers aren’t eligible to join the College

• College requirements for members are unfriendly to workers who take breaks from the field, especially women workers

• College discipline procedures require mandatory reporting by employers of an employee’s termination, regardless of whether the termination will be the subject of a grievance or arbitration

• Workers’ safety and privacy is at risk, since a college registration is open to the public

• Regulation shifts responsibility for system failures to individual workers

:::

Under suspicion: Concerns about child welfare.

"Passing the buck..."

CAS funded research indicates that many professionals overreport families based on stereotypes around racial identities. Both Indigenous and Africa-Canadian children and youth are overrepresented in child welfare due to systemic racism but for some reason a document called “Yes, You Can. Dispelling the Myths About Sharing Information with Children’s Aid Societies” was jointly released by the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario and the Ontario Provincial Advocate.

The document, targeted the same professionals who work with children that CAS research indicated already over-reported families, and was a critical reminder that a call to Children’s Aid is not a privacy violation when a professional claims it concerns the safety of a child.

You can hear former MPP Frank Klees say in a video linked below the very reason the social worker act was introduced and became law in 1998 was to regulate the "children's aid societies."

FORMER ONTARIO MPP FRANK KLEES EXPLAINS A DISTINCTION WITHOUT A DIFFERENCE WORKS.

I'M NOT A SOCIAL WORKER, I'M A CHILD PROTECTION WORKER!

TWO DECADES LATER...

The union representing child protection social workers is firmly opposed to oversight from a professional college and the Ministry of Children and Youth Services, which regulates and funds child protection, is so far staying out of it.

The report Towards Regulation notes that the “clearest path forward” would be for the provincial government to again legislate the necessity of professional regulation, which would be an appallingly heavy-handed move according to OACAS/Cupe.

:::

"Child, Youth and Family Services Act, 2017 proclaimed in force."

The new regulation was updated to only require Local Directors of Children’s Aid Societies to be registered with the College.

The majority of local directors, supervisors, child protection workers and adoption workers have social work or social service work education, yet fewer than 10% are registered with the OCSWSSW.

Unfortunately, many CASs have been circumventing professional regulation of their staff by requiring that staff have social work education yet discouraging those same staff from registering with the OCSWSSW.

Ontarians have a right to assume that, when they receive services that are provided by someone who is required to have a social work degree (or a social service work diploma) — whether those services are direct (such as those provided by a child protection worker or adoption worker) or indirect (such as those provided by a local director or supervisor) — that person is registered with, and accountable to, the OCSWSSW.

As a key stakeholder with respect to numerous issues covered in the CYFSA and the regulations, we were dismayed to learn just prior to the posting of the regulations that we had been left out of the consultation process. We have reached out on more than one occasion to request information about regulations to be made under the CYFSA regarding staff qualifications.

A commitment to public protection, especially when dealing with vulnerable populations such as the children, youth and families served by CASs, is of paramount importance. In short, it is irresponsible for government to propose regulations that would allow CAS staff to operate outside of the very system of public protection and oversight it has established through professional regulation.

Regulations under the CYFSA:

The College has worked with government to address its concerns about regulations under the new CYFSA which set out the qualifications of Children’s Aid Society (CAS) staff. Upon learning in late November that the proposed regulations would continue to allow CAS workers to avoid registration with the College, the College immediately engaged with MCYS and outlined its strong concerns in a letter to the Minister of Children and Youth Services and a submission to the Ministry of Children and Youth Services during the consultation period.

The new regulation was updated to require Local Directors of Children’s Aid Societies to be registered with the College.

We are pleased to note that, while the new regulation does not currently require CAS supervisors to be registered, we have received a "commitment" FROM THE OUTGOING WYNNE GOVERNMENT to work with the College and the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies toward a goal of requiring registration of CAS supervisors beginning January 2019.

Key concerns:

The absence of a requirement for CAS child protection workers to be registered with the College: ignores the public protection mandate of the Social Work and Social Service Work Act, 1998 (SWSSWA); avoids the fact that social workers and social service workers are regulated professions in Ontario and ignores the College’s important role in protecting the Ontario public from harm caused by incompetent, unqualified or unfit practitioners; allows CAS staff to operate outside the system of public protection and oversight that the Government has established through professional regulation; and fails to provide the assurance to all Ontarians that they are receiving services from CAS staff who are registered with, and accountable to, the College.

Since it began operations in 2000, the OCSWSSW has worked steadily and completely unseen to silently address the issue of child protection workers.

Unfortunately, many CASs have been circumventing professional regulation of their staff by requiring that staff have social work education yet discouraging those same staff from registering with the OCSWSSW.

The new regulation was updated to only require Local Directors of Children’s Aid Societies to be registered with the College.

The majority of local directors, supervisors, child protection workers and adoption workers have social work or social service work education, yet fewer than 10% are registered with the OCSWSSW.

The existing regulations made under the CFSA predated the regulation of social work and social service work in Ontario and therefore their focus on the credential was understandable.

However, today a credential focus is neither reasonable nor defensible. Social work and social service work are regulated professions in Ontario.

Updating the regulations under the new CYFSA provides an important opportunity for the Government to protect the Ontario public from incompetent, unqualified and unfit professionals and to prevent a serious risk of harm to children and youth, as well as their families.

As Minister Coteau said in second reading debate of Bill 89, "protecting and supporting children and youth is not just an obligation, it is our moral imperative, our duty and our privilege—each and every one of us in this Legislature, our privilege—in shaping the future of this province."

A "social worker" or a "social service worker" is by law someone who is registered with the OCSWSSW. Furthermore, as noted previously, the Ontario public has a right to assume that when they receive services that are provided by someone who is required to have a social work degree (or a social service work diploma), that person is registered with the OCSWSSW.

The OCSWSSW also has processes for equivalency, permitting those with a combination of academic qualifications and experience performing the role of a social worker or social service worker to register with the College.

These processes address, among other things, the risk posed by "fake degrees" and other misrepresentations of qualifications, ensuring Ontarians know that a registered social worker or social service worker has the education and/or experience to do their job.

The review of academic credentials and knowledge regarding academic programs is an area of expertise of a professional regulatory body. An individual employer will not have the depth of experience with assessing the validity of academic credentials nor the knowledge of academic institutions to be able to uncover false credentials or misrepresentations of qualifications on a reliable basis.

Setting, maintaining and holding members accountable to the Code of Ethics and Standards of Practice. These minimum standards apply to all OCSWSSW members, regardless of the areas or context in which they practise. Especially relevant in the child welfare context are principles that address confidentiality and privacy, competence and integrity, record-keeping, and sexual misconduct.

Maintaining fair and rigorous complaints and discipline processes. These processes differ from government oversight systems and process-oriented mechanisms within child welfare, as well as those put in place by individual employers like a CAS. They focus on the conduct of individual professionals.

Furthermore, transparency regarding referrals of allegations of misconduct and discipline findings and sanctions ensures that a person cannot move from employer to employer when there is an allegation referred to a hearing or a finding after a discipline hearing that their practice does not meet minimum standards.

Submission-re-Proposed-Regulations-under-the-CYFSA-January-25-2018. OCSWSSW May 1, 2018

If you have any practice questions or concerns related to the new CYFSA, please contact the Professional Practice Department at 416-972-9882 or 1-877-828-9380 or email practice@ocswssw.org.

:::

Between 2008/2012 natural causes was listed as the least likely way for a child in Ontario's care to die at 7% of the total deaths reviewed (15 children) while "undetermined cause" was listed as the leading cause of death of children in Ontario's child protection system at "43%" of the total deaths reviewed (92 children).

2009: Why did 90 children in care die?

Discredited hair-testing program harmed vulnerable families across Ontario, report says.

2013: Nancy Simone, a president of the Canadian Union of Public Employees local representing 275 workers at the Catholic Children’s Aid Society of Toronto, argued child protection workers already have levels of oversight that include unregistered unqualified workplace supervisors, family court judges, coroners’ inquests and annual case audits by the ministry and the union representing child protection workers is firmly opposed to ethical oversight from a professional college, and the Ministry of Children and Youth Services, which regulates and funds child protection, is so far staying out of the fight.. Nancy Simone says, “Our work is already regulated to death.”

YET BAD THING KEEP HAPPENING TO CHILDREN...

A sociopath is a term used to describe someone who has antisocial personality disorder (ASPD). People with ASPD can't understand others' feelings. They'll often break rules or make impulsive decisions without feeling guilty for the harm they cause. People with ASPD may also use “mind games” to control friends, family members, co-workers, and even strangers. They may also be perceived as charismatic or charming.

:::

Head of Motherisk probe had ties to Sick Kids

By JACQUES GALLANT Staff Reporter

Fri., Feb. 12, 2016

Questions are being raised about the retired judge chosen by the provincial government to head a two-year commission reviewing child protection cases that used flawed hair-test results from the Hospital for Sick Children’s Motherisk laboratory.

Justice Judith Beaman has prior legal connections to Sick Kids, the Star has learned. While working as a lawyer in private practice in the late 1980s and early 1990s, she advised the hospital’s Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect team.

Justice Judith Beaman, who will lead the second Motherisk commission.

The SCAN team would later come under fire for its actions during that period, after a public inquiry looked into cases by disgraced pathologist Charles Smith, who worked closely with SCAN members and whose findings led in some instances to wrongful convictions.

“The government has complete confidence that Justice Beaman’s career and experience as a judge and a lawyer will not place her in a conflict with respect to her responsibilities as commissioner,” said Christine Burke, a spokeswoman for Ontario Attorney-General Madeleine Meilleur.

Burke confirmed that Beaman, considered a family law expert, provided advice to the SCAN team “to support preparations for court appearances,” adding that it was over 25 years ago and has no connection with the matters being dealt with at the Motherisk commission.

The commission, which began its work last month, did not make Beaman available for an interview.

A spokesman said Beaman never advised — nor even recalls meeting — Smith, and that aside from discussing court presentations with the SCAN team, she also flagged case law she thought would be relevant to their work during a period of about two years.

The issue of Beaman heading the commission has led to concern from the Criminal Lawyers’ Association and has been raised in a letter to Meilleur from a lawyer representing a woman affected by Motherisk.

“Fairness and impartiality are cornerstones of our justice system. As a result, judges must be and appear to be unbiased,” said criminal defence lawyer Daniel Brown, a Toronto director of the CLA.

“There is no concern about the integrity or impartiality of Justice Beaman, but because this is a public review, our organization is very concerned that her decision might appear to be coloured by her prior associations with Sick Kids Hospital.”

Christine Rupert, whose two daughters were removed at birth and later adopted out, wants answers from the government about Beaman.

Her daughters remained in foster care because, at least in part, of Motherisk hair tests that showed Rupert was a heavy cocaine user — a finding she has always fiercely denied and has gone to great lengths to disprove.

“I simply want to be assured that Justice Beaman was not involved in any way whatsoever with the previous problems at the Hospital for Sick Children,” she told the Star, referring to the Smith scandal and the pathologist’s association with the SCAN team.

Her lawyer, Julie Kirkpatrick, raised Rupert’s concern in a Jan. 17 letter to Meilleur, but has yet to hear back.

“I have a duty to my client to ask questions on her behalf,” she told the Star. “I do look forward to hearing back from the government so that I can reassure my client. This is very important to her.”

It is not unusual for judges to have represented many different interests and parties before their call to the bench, said the head of the Family Lawyers Association.

“Generally, the family law bar was positive about (Beaman’s) appointment as she is seen as someone experienced and knowledgeable about child protection law,” said Katharina Janczaruk.

Beaman’s name came up in 2008 at the Goudge Inquiry, which was looking into errors made by Smith in child death cases.

Dr. Katy Driver, a member of the SCAN team, told inquiry counsel Linda Rothstein that “Judy Beeman” would come in about once a month and “we would discuss some of the concerns that we would have had over different cases, different court appearances of anyone of us,” according to a transcript.

Driver is out of the country and could not be reached for comment by the Star.

Rothstein’s questions to Driver followed a discussion at the inquiry about a meeting of the SCAN team in which they shrugged off a 1991 ruling by a judge who had acquitted a babysitter of killing a baby. The verdict came after a number of forensic experts disputed the evidence put forward by Smith and the SCAN team.

The judge, Patrick Dunn, was described in minutes from that meeting as a “family court judge at the bottom of the heap,” and that his ruling had “no presidential value re: medical evidence,” the inquiry heard.

Known as the “Amber case,” it was the first case that seriously called into question Smith’s work and a key moment in what would become a national scandal. The outright dismissal of the judge’s ruling by the SCAN team was described as a missed opportunity at the public inquiry.

It was not clear in the inquiry transcript if Beaman attended that meeting of the SCAN team or helped them in preparing for the trial.

The Motherisk commission spokesman told the Star that Beaman “has no recollection of speaking to the team about any particular court decisions,” but that her advice would never have been to disregard a ruling.

From a legal ethics perspective, Beaman’s appointment as head of the commission seems to have the appearance of a conflict, said Osgoode Hall law professor Allan Hutchinson, who is not involved with the commission or Motherisk.

“Somebody will easily be able to paint her report — however unjustified — by saying: ‘Look, she used to work for (Sick Kids),’ ” he said.

:::

What is a Logical Fallacy?

A logical fallacy is an error in reasoning common enough to warrant a fancy name. Knowing how to spot and identify fallacies is a priceless skill. It can save you time, money, and personal dignity. There are two major categories of logical fallacies, which in turn break down into a wide range of types of fallacies, each with their own unique ways of trying to trick you into agreement.

A Formal Fallacy is a breakdown in how you say something. The ideas are somehow sequenced incorrectly. Their form is wrong, rendering the argument as noise and nonsense.

An Informal Fallacy denotes an error in what you are saying, that is, the content of your argument. The ideas might be arranged correctly, but something you said isn’t quite right. The content is wrong or off-kilter.

For the purposes of this article, when we say logical fallacies, we refer to informal fallacies. Following is a list of the 15 types of logical fallacies you are most likely to encounter in discussion and debate.

Appeal to Ignorance (argumentum ad ignorantiam)

Any time ignorance is used as a major premise in support of an argument, it’s liable to be a fallacious appeal to ignorance. Naturally, we are all ignorant of many things, but it is cheap and manipulative to allow this unfortunate aspect of the human condition to do most of our heavy lifting in an argument.

An appeal to ignorance isn’t proof of anything except that you don’t know something.

Interestingly, appeal to ignorance is often used to bolster multiple contradictory conclusions at once. Consider the following two claims:

“No one has ever been able to prove definitively that extra-terrestrials exist, so they must not be real.”

“No one has ever been able to prove definitively that extra-terrestrials do not exist, so they must be real.”

If the same argument strategy can support mutually exclusive claims, then it’s not a good argument strategy.

An appeal to ignorance isn’t proof of anything except that you don’t know something. If no one has proven the non-existence of ghosts or flying saucers, that’s hardly proof that those things either exist or don’t exist. If we don’t know whether they exist, then we don’t know that they do exist or that they don’t exist. Appeal to ignorance doesn’t prove any claim to knowledge.

Ad Hominem Fallacy

When people think of “arguments,” often their first thought is of shouting matches riddled with personal attacks. Ironically, personal attacks run contrary to rational arguments. In logic and rhetoric, a personal attack is called an ad hominem. Ad hominem is Latin for “against the man.” Instead of advancing good sound reasoning, an ad hominem replaces logical argumentation with attack-language unrelated to the truth of the matter.

More specifically, the ad hominem is a fallacy of relevance where someone rejects or criticizes another person’s view on the basis of personal characteristics, background, physical appearance, or other features irrelevant to the argument at issue.

An ad hominem is more than just an insult. It’s an insult used as if it were an argument or evidence in support of a conclusion.

Verbally attacking people proves nothing about the truth or falsity of their claims. Use of an ad hominem is commonly known in politics as “mudslinging.” Instead of addressing the candidate’s stance on the issues, or addressing his or her effectiveness as a statesman or stateswoman, an ad hominem focuses on personality issues, speech patterns, wardrobe, style, and other things that affect popularity but have no bearing on their competence. In this way, an ad hominem can be unethical, seeking to manipulate voters by appealing to irrelevant foibles and name-calling instead of addressing core issues. In this last election cycle, personal attacks were volleyed freely from all sides of the political aisle, with both Clinton and Trump facing their fair share of ad hominem fallacies.

Ad hominem is an insult used as if it were an argument or evidence in support of a conclusion.

A thread on Quora lists the following doozies against Hillary Clinton: “Killary Clinton,” “Crooked Hillary,” “Hilla the Hun,” “Shillary,” “Hitlery,” “Klinton,” “Hildebeest,” “Defender of Child rapists,” “Corporate Whore,” “Mr. President,” “Heil Hillary,” “Wicked Witch of the West Wing,” “Robberty Hillham Clinton,” “Mrs. Carpetbagger”, and the decidedly unsubtle, “The Devil.”

The NY Daily News offers an amusing list of insults against Donald Trump: “Short fingered Vulgarian,” “Angry Creamsicle,” “Fascist Carnival Barker,” “F*ckface von Clownstick,” “Decomposing Jack-O-Lantern,” “Chairman of the Saddam Hussein Fanclub,” “Racist Clementine,” “Sentient Caps Lock Button,” “Cheeto Jesus,” “Tangerine Tornado,” and perhaps the most creative/literary reference, “Rome Burning in Man Form.”

The use of ad hominem often signals the point at which a civil disagreement has descended into a “fight.” Whether it’s siblings, friends, or lovers, most everyone has had a verbal disagreement crumble into a disjointed shouting match of angry insults and accusations aimed at discrediting the other person. When these insults crowd out a substantial argument, they become ad hominems.

Strawman Argument

It’s much easier to defeat your opponent’s argument when it’s made of straw. The Strawman argument is aptly named after a harmless, lifeless, scarecrow. In the strawman argument, someone attacks a position the opponent doesn’t really hold. Instead of contending with the actual argument, he or she attacks the equivalent of a lifeless bundle of straw, an easily defeated effigy, which the opponent never intended upon defending anyway.

The strawman argument is a cheap and easy way to make one’s position look stronger than it is. Using this fallacy, opposing views are characterized as “non-starters,” lifeless, truthless, and wholly unreliable. By comparison, one’s own position will look better for it. You can imagine how strawman arguments and ad hominem fallacies can occur together, demonizing opponents and discrediting their views.

With the strawman argument, someone attacks a position the opponent doesn’t really hold.

This fallacy can be unethical if it’s done on purpose, deliberately mischaracterizing the opponent’s position for the sake of deceiving others. But often the strawman argument is accidental, because the offender doesn’t realize the are oversimplifying a nuanced position, or misrepresenting a narrow, cautious claim as if it were broad and foolhardy.

Read more:

:::

A sociopath is a term used to describe someone who has antisocial personality disorder (ASPD). People with ASPD can't understand others' feelings. They'll often break rules or make impulsive decisions without feeling guilty for the harm they cause. People with ASPD may also use “mind games” to control friends, family members, co-workers, and even strangers. They may also be perceived as charismatic or charming.

:::

Industry self-regulation is the process whereby members of an industry, trade or sector of the economy monitor their own adherence to legal, ethical, or safety standards, rather than have an outside, independent agency such as a third party entity or governmental regulator monitor and enforce those standards.[1]

Self-regulation may ease compliance and ownership of standards, but it can also give rise to conflicts of interest.

:

Youth homelessness linked to foster care system in new study

The study, to be released Wednesday, found nearly three out of every five homeless youth were part of the child welfare system at some point in their lives, a rate almost 200 times greater than that of the general population.

:

If any organization, such as a corporation or government bureaucracy, is asked to eliminate unethical behavior within their own group, it may be in their interest in the short run to eliminate the appearance of unethical behavior, rather than the behavior itself, by keeping any ethical breaches hidden, instead of exposing and correcting them.

An exception occurs when the ethical breach is already known by the public. In that case, it could be in the group's interest to end the ethical problem to which the public has knowledge, but keep remaining breaches hidden.

Another exception would occur in industry sectors with varied membership, such as international brands together with small and medium size companies where the brand owners would have an interest to protect the joint sector reputation by issuing together self-regulation so as to avoid smaller companies with less resources causing damage out of ignorance.

Similarly, the reliability of a professional group such as lawyers and journalists could make ethical rules work satisfactorily as a self-regulation if they were a pre-condition for adherence of new members.

An organization can maintain control over the standards to which they are held by successfully self-regulating. If they can keep the public from becoming aware of their internal problems, this also serves in place of a public relations campaign to repair such damage.

SEE: “I Am Your Children’s Aid” campaign is a provincial campaign designed to educate/deceive Ontarians about the role of CASs in their community and ways they can get involved in protecting children and building stronger families. It is also to be used as a tool to recruit foster, adoptive parents and volunteers. This campaign brings to life stories of the young men and women.

The cost of setting up an external enforcement mechanism is avoided. If the self-regulation can avoid reputational damage and related risks to all actors in the industry, this would be a powerful incentive for a pro-active self-regulation [without the necessity to assume it is to hide something].

Self-regulating attempts may well fail, due to the inherent conflict of interest in asking any organization to police itself.

If the public becomes aware of this failure, an external, independent organization is often given the duty of policing them, sometimes with highly punitive measures taken against the organization.

The results can be disastrous, such as a child welfare society with no external, independent oversight, which may commit human rights violations against the public. Not all government funded private businesses will voluntarily meet best practice standards, leaving some or most families exposed.

Governments may prefer to allow an industry to regulate itself but maintain a watching brief over the effectiveness of self-regulation and be willing to introduce external regulation if necessary. For example, in the UK, the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee in 2015 investigated the role of large accountancy firms in relation to tax avoidance and argued that "Government needs to take a more active role in regulating the tax industry, as it evidently cannot be trusted to regulate itself".

:::

Social Work and Social Service Work Act, 1998, S.O. 1998, c. 31

PART V: APPEALS TO COURT

31 (1) A party to a proceeding before the Registration Appeals Committee, the Discipline Committee or the Fitness to Practise Committee may appeal to the Divisional Court, in accordance with the rules of court, from the decision or order of the committee. 1998, c. 31, s. 31 (1).

Same

(2) For purposes of this section, a person who requests a review under section 20 is a party to the review by the Registration Appeals Committee. 1998, c. 31, s. 31 (2).

Certified copy of record

(3) On the request of a party desiring to appeal to the Divisional Court and on payment of the fee prescribed by the by-laws for the purpose, the Registrar shall give the party a certified copy of the record of the proceeding, including any documents received in evidence and the decision or order appealed from. 1998, c. 31, s. 31 (3).

Powers of court on appeal

(4) An appeal under this section may be made on questions of law or fact or both and the court may affirm or may rescind the decision of the committee appealed from and may exercise all powers of the committee and may direct the committee to take any action which the committee may take and that the court considers appropriate and, for the purpose, the court may substitute its opinion for that of the committee or the court may refer the matter back to the committee for rehearing, in whole or in part, in accordance with any directions the court considers appropriate. 1998, c. 31, s. 31 (4).

Effect of appeal

(5) An appeal from a decision or order of a committee mentioned in subsection (1) does not operate as a stay of that decision or order. 1998, c. 31, s. 31 (5).

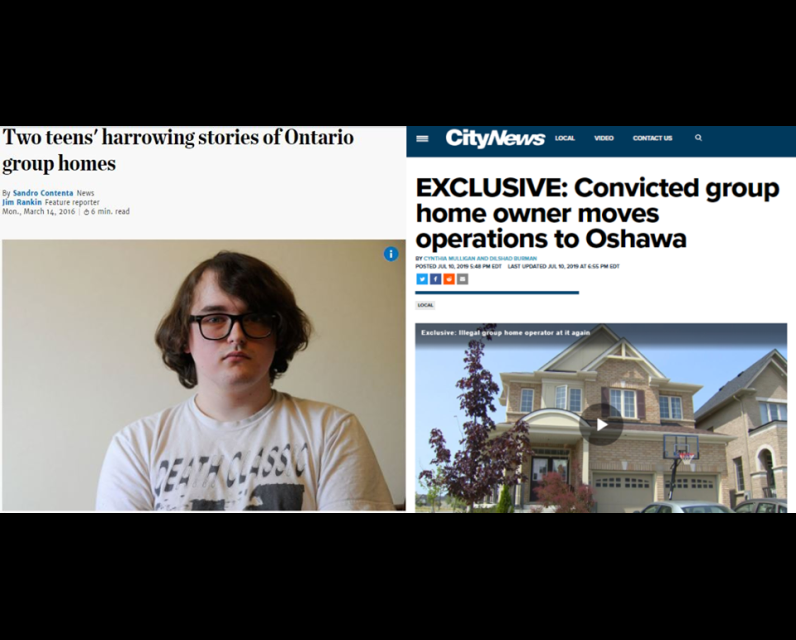

2019 - EXCLUSIVE: Convicted group home owner moves operations to Oshawa.

The man at the centre of an in-depth CityNews investigation into illegal group homes is now accused of moving his operations to Oshawa.

Authorities in Oshawa believe Winston Manning is in breach of probation and say more charges are pending, adding that vulnerable people have been put in danger.

In 2016, Manning was a key figure in an Ontario Provincial Police probe into illegal group homes. The investigation found that people with physical and mental health issues were living in deplorable conditions: mattresses on the floor, inadequate food, mouse feces and the smell of urine in the homes.

The findings were corroborated by a former tenant at the time, who was identified only as Dave.

“[It was] filthy. Turn on a light in the middle of the night and you could see the cockroaches moving, almost like a carpet. There were thousands of them,” he told CityNews.

Just 11 months ago, Manning plead guilty to to multiple fire code violations in relation to several illegal group homes in Toronto. He and his company, Comfort Residential Group Homes, were fined more than $80,000, put on probation and ordered not to operate any illegal homes.

Shortly after, Manning was charged again after a fire broke out at an illegal rooming house in the Victoria Park area in November 2018. Fire officials believe it was around the same time he started operating in Oshawa.

On Tuesday, authorities removed nine tenants from a residence in Oshawa — the fourth illegal home operated by Manning in that city. Three staff members were also in the home.

Carson Ryan, Fire Prevention Inspector with Oshawa Fire, says fire safety is one of the main issues in the home.

“We’ve had problems with fire separation issues, smoke alarms, carbon monoxide alarms — which are all required in any home. And there is a higher requirement in vulnerable occupancy care in these homes, for them to be compliant,” he tells CityNews

“What’s concerning the most is a large number of residents there don’t know where they are, how they got there, how long they’ve been there or how to contact anybody,” he adds. “They lose all their documentation coming into the house, they lose their cellphones, their medications are dispensed for them, allegedly, and they don’t have anybody to turn to.”

Oshawa fire officials say the house is in violation of the fire code and vulnerable residents, who Carson says have both physical and cognitive limitations, would not be able to get out safely in an emergency.

“Not only are [illegal group homes] a danger to the people within, they are a danger to first responders going into the homes, not expecting typically 12 people inside of a single detached dwelling. It’s also an issue for neighbours for fire exposures,” says Carson.

The residents are allegedly being cared for, but Carson says from what he’s seen, he doubts they are receiving the level of care they need. He describes an upsetting scene the very first time he stepped into the home.

“The first time I walked into this home there was an adult male wearing a soiled diaper, wearing only a t-shirt, wandering around the house trying to find his way and how he got there. He was brought there the night before. A lot of questions that he asked, I unfortunately didn’t have an answer for. He did look like he was in a bit of a desperate situation,” he says.

Officials are also concerned that residents, who pay about $1,000 per month to share a bedroom, aren’t being fed properly. Carson says he’s never seen any nutritious food in the home, only instant pasta and noodles. A resident who lives nearby told Citynews a woman from the home would often knock on neighbours’ doors, asking for food and cigarettes.

The condition of the home is described as relatively clean, except for the smell of urine and feces throughout the home.

CityNews reached out to Manning several times via phone but did not get a response.

Carson says charges are pending in one of the other three cases of illegal group homes run by Manning in Oshawa – including enforcement of the probation orders obtained by Toronto Fire.

Officials in Toronto do not believe Manning is currently operating any illegal group homes within the city.

2016: An expert panel has delivered a report to the Ontario government on the troubled state of residential care for our most vulnerable children. It will soon be made public. Rarely heard are the voices of the youth themselves. Here are the stories of Simon and Lindsay.

Simon’s story: Staffer ‘would try to pick fights’

Simon came home from high school on a fall day in 2013 to find police cars in front of his east-end Toronto home. His mother was “crying her eyes out.” Children’s aid, backed by police, had come to take Simon and his two younger sisters.

The Children’s Aid Society of Toronto had placed the family under supervision that April. Six months later, it decided matters had not improved.

In documents, the society said the children had missed about two years of school. Their home was a mess and the society feared for the children’s health. Parents were considered negligent, allowing their 12-year-old daughter to stay out until 1:30 a.m. and blocking attempts to help the children deal with “self-destructive” behaviour.

Related: Children's aid societies urge Ontario group-home overhaul

Simon calls the allegations “bizarre and false.” He blames a child protection worker he describes as inexperienced.

On one point, however, Simon and the society would likely agree: when children are taken from parents deemed neglectful or abusive, their group home care should be better than the care they left behind. Simon insists his was worse.

YOU MIGHT BE INTERESTED IN...

Shedding light on the troubles facing kids in group homes

Children's aid societies urge Ontario group-home overhaul

He was 16 and bounced to four group homes in one year. He says he saw staff repeatedly bullying and verbally abusing residents. “It was very scary,” says Simon, now 18. (The Star is not using his last name because his sisters remain in care.)

Simon’s longest stretch was at a Hanrahan Youth Services group home in Scarborough. He says he was so frightened by what he saw that he began to secretly record incidents with his iPod. One recording, which he posted online, captures a man — Simon identifies him as a Hanrahan staffer — shouting at a young male resident. The dispute began, Simon says, because the youth refused to respect house rules and go to his room at 9 p.m. It escalated, the man accusing the youth of telling housemates he would head-butt him. His voice full of anger and menace, the man dares a calm-sounding youth to do it.

“Head-butt me!” the man shouts. “I’m right here in front of you. Head-butt me! Do it! Do it!”

“You going to call the cops on me,” the youth says.

“Who will call the cops on you? For what? Head-butt me!” the man insists.

“You are a problem,” the youth replies.

The staffer, Simon says, “used to have these episodes every day with the kids. He would try to pick fights. He knew that if these kids punched him he would have the right to restrain them, and he would use excessive force. He would bang their head up against the floor and they would be bleeding.”

Simon also describes often being locked out of the home when he arrived after curfew.

Bob Hanrahan, who owns and operates Hanrahan Youth Services, said in an email he could not comment on Simon’s allegations “due to confidentiality restrictions.” Training for home staff, Hanrahan added, includes a course on managing aggressive behaviour.

Simon was moved to two other group homes, where he says bullying and the physical restraint of young residents were common. A third was the only one he could stomach.

On Oct. 27, 2014, a judge agreed to return him to his mother’s care.

“Kids suffer more damage in group homes than they do when they’re living with their parents,” Simon says. “That’s one thing the government and the public should know about group homes.”

Lindsay’s story: Enters home at 12, pregnant at 14

YOU MIGHT BE INTERESTED IN...

Examples of tough situations in Toronto group homes

Toronto doctor stripped of licence after panel hears she had sex with cancer patient in his hospital bed

Lindsay’s family asked York Region Children’s Aid Society for help when she became too much to handle.

Lindsay, who is autistic, was “aggressive, specifically towards myself and her father,” says Elizabeth, Lindsay’s grandmother and primary caregiver at the time. “We were afraid that somebody was going to get hurt.”

In a voluntary arrangement, Lindsay was placed in a foster home, but her foster mom couldn’t deal with her either. Three months later, at age 12, she was moved to a co-ed group home in Scarborough, run by East Metro Youth Services.

Lindsay, now 15, was placed in a co-ed Scarborough group home when she was 12. Here, she looks at a serious occurrence report from the home that involved her.

It would be home for 21 months, until March 2015. Lindsay “grew up really fast,” says her father, Eric, whose struggles with depression made it impossible to be her main caregiver.

Lindsay says she was exposed to “drugs, parties, alcohol, abuse, self-harm. People with mental disabilities who weren’t being treated right.” (Names have been changed for this story because, by law, a minor in care cannot be identified.)

The group home accommodated eight young people up to age 18. Lindsay was the youngest. The kids often got in trouble with staff, says Lindsay, and punishment included extra chores and being “isolated in your room.” Lindsay and her family contacted the Star after Lindsay recognized an incident in a Star story. In that incident, Lindsay and another girl, upset with staff, left without permission and bounced a basketball down the street. “We weren’t doing anything illegal.”

They returned but were locked out. It was cold, so the other girl made a small fire in the backyard. Staff ordered it put out. The other girl complied, says Lindsay, and the two pounded on the door.

“It had been almost an hour,” says Lindsay. “I couldn’t feel my face. So we just kicked in the door.”

Police took the girls away in handcuffs. Lindsay was not charged; she says the other girl never returned.

Lindsay says police were often called when kids broke house rules. She describes most staff as yelling a lot and unable to properly deal with kids with mental health and behavioural issues.

In a statement to the Star, East Metro Youth Services said staff are yearly “offered specialized conflict resolution and de-escalation training,” which results in “minimized” need to call police. They are only called “if there is a danger of harm to residents or staff.”

A Star analysis of Toronto serious occurrence reports from 2013 shows that of 41 reports filed by Lindsay’s home, 13 involved police, or 32 per cent. That is below the average of 39 per cent for Toronto group homes that year.

Lindsay says the kids were unwatched for long periods at night and could sneak out, claiming “a lot” of sex among residents when she arrived in 2013. She says she was 13 when she first asked staff about getting birth control pills, which would require an appointment with a doctor. The appointment, she says, was never made.

At 14, Lindsay got pregnant by a fellow resident. In its statement, East Metro said condoms were always available, and all prescription medication requires signatures by resident and family or guardian. The agency would not comment on her case, but said: “Ultimately, it is an individual’s choice to use birth control measures. When a young person is worried she might be pregnant, pregnancy tests are provided in all cases, without exception.”

The home closed in March 2015. The agency says it was due to “reduced demands” driven, in part, by a greater push by children’s aid societies to find alternatives. It runs a second group home.

The closure disrupted the school year for Lindsay, who, earlier than planned, moved back home to live with her grandparents and father. She gave birth to a girl. The baby was adopted in a private arrangement and is doing well says Lindsay’s grandmother, Elizabeth.

Lindsay, however, “is struggling” with both school and post traumatic stress brought on by her experience at the group home, says Elizabeth. She also moved schools last fall after a student “grabbed her phone” and discovered photos of her with the baby. In the past three years, she has been to five different schools.

Elizabeth calls her granddaughter “one of the fortunate ex-group homers,” with a supportive family.

Although the family encountered some good people after calling on children’s aid for help, they say they would never ask for such help again.

“The children’s aid society,” says Lindsay’s dad, “sent me home a pregnant 14-year-old daughter.”

:::

‘No one listened’: How reports of sexual abuse in an Ontario foster home were allegedly dismissed for years..

Global provides a quote from one of the victims demonstrating that neighbours wondered how Joe and Janet Holmes were able to receive and care for children. The same victim had her contact information distributed by her abusers to people in the town, who then sent her sexually inappropriate messages and contributed to her abuse.

Tragically, foster home scarcity may have contributed to the ongoing neglect of the Holms’ crimes. One victim, whose name was redacted by Global to protect their identity, said her attempt to report her foster parent, Joe Holms, forcing her to “cuddle” on the couch simply resulted in him being told “to stop cuddling the children.” Revelation like this may have led to Justice Geoffrey Griffin, the judge who oversaw the conviction of the Holms to comment “The idea that the Children’s Aid Society didn’t know or, or shouldn’t have been aware that something was going on, is hard for me to accept.”

While both Joe and his wife Janet were sentenced to jail time in 2011 for their various, horrific abuses of children, they were far from the only ones. Global reports the last foster family to be convicted with the abuse of children in their care in the Prince Edward county system was in 2015.

Some say the abuse discovered in foster homes across the county went undetected for so long due to systemic failures at the Prince Edward County Children’s Aid Society. The judge who presided over the Holms’ criminal case called the abuse so outrageous that he hoped a public inquiry would be launched.

In April 2018, three years after the last conviction in the Prince Edward County abuse cases, OPP charged the former executive director of Prince Edward County Children’s Aid Society, Bill Sweet,

Bill Sweet, the executive director of the Prince Edward County Children’s Aid Society, was charged in 2018 with 10 counts of neglect, and 10 counts of failing to provide the necessities of life. His preliminary trial begins in July 2019, and his lawyer asserts that he will defend himself against the charges.

:::

Woman charged with sex assault of minors worked at male CAS group-home at time of alleged offences.

The Belleville Ont., woman who was charged with several sex-related crimes involving minors worked at a Children’s Aid Society youth group home at the time of her alleged offences.

On Thursday, Belleville police charged 48-year-old Sandra Forcier of Belleville with two counts of sexual assault, two counts of sexual exploitation of a youth under the age of 18 and one count of sexual interference.

:::

Crown Ward Class Action (Children who suffered abuse before and while they were Crown wards, including in foster care and foster homes, and while in the care of the Children’s Aid Society (“CAS”)).

This class action claims that the Ontario government systematically failed to take all necessary steps to protect the legal rights and claims of children in its care.

In Ontario, a child may be removed from the care of his or her parents and put into the care of the Province for reasons that include physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, or neglect. In Ontario, permanent wards for whom the Province has legal responsibility are called Crown wards.

Crown wards were victims of criminal abuse, neglect and tortious acts as children, and as a result of which, were removed from the care of their families and placed under the care of the Province of Ontario. These children were also victims of abuse, neglect, and tortious acts while they were under the age of 18 and in the care of Ontario.

As a result of the crimes and torts committed against them prior to and during their Crown Wardship, the class members were entitled to apply for compensation from the Criminal Injuries Compensation Board and to commence proceedings for civil damages.

The suit claims the province failed to take all necessary steps to protect the rights of Crown wards to apply for compensation from the Criminal Injuries Compensation Board or to file personal injury claims for children who were abused prior to or while in the care of the Province.

The class action seeks to include all persons who became Crown Wards in Ontario on or after January 1, 1966, the date that the Province of Ontario voluntarily accepted legal responsibility and guardianship of Crown wards.

Please contact Koskie Minsky LLP with any questions:

Email: ocwclassaction@kmlaw.ca

Toll Free Hotline: 1.866.778.7985

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS

DOCUMENTS

FAQS

CONTACTS

:::

The Cornwall Whitewash.

With $53 million dollars no one could find any signs of the respectable pedophile porn ring operating in Ontario, beside the first 34 victims and secret multi-million dollar settlements..

The Respectable Pedophiles of Ontario.

The 80's: There were 34 victims in a Cornwall child-molestation scandal, but even after a four-year, $53 million public inquiry no one knows if an organized pedophile ring was operating in Eastern Ontario.

In the 1980s, Canadians were shocked into awareness of the widespread evil of child sexual abuse. In Ontario alone, the names Cornwall, Prescott and London became synonymous with "respectable" pedophile rings -- lawyers, doctors, police officers and Catholic clergymen -- that for decades preyed on society's most vulnerable boys.

In 1992, when the local Catholic church, in an effort to avert a criminal case, paid $32,000 in a private settlement to someone who said he was abused as an altar boy by a parish priest. The priest's guilt or innocence has never been tested in court.

Then along came a crusading cop named Perry Dunlop. Mr. Dunlop was scandalized that his own police force had decided there wasn't enough evidence to nail the priest. It was personal; Mr. Dunlop was a fervent convert to Catholicism, and the priest was his family priest. Mr. Dunlop now lives in BC and refuses to return to Ontario.

Four of the accused are dead. One doctor went so far as to commit suicide (now - I don't know the actual facts surrounding the suicide but it honestly doesn't sound like the act of an innocent doctor wrongly accused)

The Cornwall Public Inquiry was urged to debunk rumors of pedophile ring and the only thing $53 million dollar, four year inquiry was able to determine as fact were, lawyers, doctors, police officers and Catholic clergymen, the children's aid society and other justice officials refused to co-operate with the inquiry and that there were 34 victims that were apparently passed around., Now the same lawyers, doctors, police officers and Catholic clergymen that had stood accused focused on services and programs to prevent the victimization of, or help the victims heal.

"There is no doubt that this commission was formed largely in response to the persistence of this story," David Sherriff-Scott, lawyer for the Diocese of Alexandria-Cornwall, submitted to the inquiry. "The commission, therefore, should unequivocally and unreservedly put the story to rest and declare that, after more than three years of probing, the story is false."

The last effort to track down the sex abusers was called Project Truth. It was launched in 1997 by the Ontario Provincial Police after the local police force was torn apart by the controversy. Since then, Project Truth has laid more than 100 charges against 14 men.

But, so far, there has been not a single conviction. Six of the cases have yet to proceed. Four of the accused are dead. One man was acquitted; one was found unfit to stand trial; one had his charges dropped last fall. And one case was thrown out of court last week after a spectacular prosecutorial debacle. That case was Jacques Leduc's.

Commissioner G. Normand Glaude released his 2,396-page report Tuesday, exposing "a combination of systemic failures, insensitivity to complaints,

-

(and a) reluctance to act" on the part of church, school, the children's aid society, police and justice officials.

-

That fueled "speculation" (34 victims isn't just speculation) – stoked by the media, and politicians making supposedly "inaccurate" statements – of a child molesters' ring at large in the area for years.

"I heard evidence that suggested that there were cases of joint abuse, passing of alleged victims and possibly passive knowledge of abuse. I am not making a pronouncement on whether a ring existed or not," Glaude wrote in his report.

Ont. premier questions cost of Cornwall sex abuse inquiry

Barbara Kay. National Post.

Margaret Wente. The Globe and Mail.

The Canadian Press. CBC news.

Robert Benzie, Rob Ferguson. The Toronto Star.

:::

Cornwall sex abuse victims given large settlements

Published Thursday, June 10, 2010 12:20PM EDT ctvottawa.ca

Some victims of the Cornwall sex abuse scandal are receiving large financial settlements after decades of allegations that a cover-up of a pedophile ring existed in the eastern Ontario city, CTV Ottawa has learned.

The sex abuse scandal was uncovered in the early 1990s. A public inquiry ended in December 2009 after four years. The inquiry found the Catholic Church, police, the Ontario government and the legal system all failed to protect children from sexual predators.

Now, Ontario's attorney general has confirmed to CTV that several financial settlements have been reached with victims, and more lawsuits are outstanding.

The Project Truth inquiry into a pedophile ring cover-up and sex abuse allegations in Cornwall ended in December 2009.

Alleged victim Steve Parisien says the public has a right to know about large settlements paid out to sex abuse victims.

Although confidentiality agreements could mean taxpayers will never learn the true cost of the settlements, a former MPP predicts the payouts will total tens of millions of dollars.

-

"I would look at somewhere between $70-100 million," said Garry Guzzo, a former Conservative MPP who blew the whistle on the scandal and pushed for a public inquiry.

-

"It's a lot of money coming from very few taxpayers, and the people of the Catholic Church are taxpayers."

While sources have told CTV the payouts are in the millions, alleged victim Steve Parisien says some individuals are getting less than $20,000.

"I think parishioners and taxpayers have a right to know how much has been paid out," he said.

A lawyer representing dozens of the victims wouldn't reveal how much money was paid. However, he confirmed several settlements have been reached with the Catholic diocese, the Ontario government and other Catholic organizations.

-

There are also several cases in the works against the Children's Aid Society.

-

"You know the confidentiality agreement - never going to trial, never allowing it to become public - there's an element of hush money."

Although Parisien hasn't received a settlement, he is hoping to get some compensation for his experience.

He says while no amount of money will change his life, it will help validate what he went through.

"Just for my loss of wages - that's all I seek. I don't want nothing else from these people, they've done enough damage. And they have to sleep with themselves at night."

With a report from CTV Ottawa's Catherine Lathem

:::

Three CAS cases settled.

When it was filed in 2013, the civil suits totaled $14 million ($2.8 million per plaintiff).

Each plaintiff initially claimed $350,000 for pain and suffering, in addition to $1 million each for loss of future earnings and another $1 million for punitive damages. They sought $100,000 in future care costs, plus $100,000 for special damages and $250,000 for aggravated damages.

Two outstanding plaintiffs will be addressed shortly, Bonn said.

“We continue to work on those,” he said. “We intend to mediate those.”

The suit directed at the CAS also targets four former foster parents, two are now serving prison terms for sexual abuse of children placed in their care. A third convicted predator’s case is now before the Ontario Court of Appeal.

:::

Several years back, Annie and her now-ex-husband took their 15-year-old son Nick to Highland Shores Children’s Aid Society (formerly Prince Edward County CAS), hoping to get him help. But almost a year after his death, they feel Nick’s time in the Belleville, Ont.-area Children’s Aid Society group home was the spark that led to a violent criminal streak and his eventual suicide.

“Nick was just battling a lot of things with drugs and alcohol,” Annie said. “He tried his best to live a good life. In his final letter to me, he (said he) was heading down a life he didn’t want.”

READ MORE: Belleville woman charged with sexual exploitation worked at Children’s Aid at time of alleged offences

A Global News investigation has uncovered stories from the Children’s Aid group home where Nick lived for a short time in 2012 and 2013, where already vulnerable teenage boys were allegedly taking and selling drugs, stealing from their classmates and using money from those exploits to buy tattoos, drugs and alcohol — and all of this was allegedly encouraged by one employee.

(Both Annie and Nick’s names have been changed to protect Nick’s identity. Nick’s father would not consent to an interview.)

In late January 2019, 48-year-old Sandra Forcier, a former supervisor of the youth home on Willett Road in Belleville, Ont., was charged with the historic sexual assault of two underage boys. Forcier’s case is still before the court, and a trial date has yet to be set.

None of the allegations made against Forcier have been proven in court. Edward Kafka, a lawyer for Forcier, refused to comment for this story.

“There shall be no comment from Ms. Forcier or this office in relation to this investigation. I trust I have made our position crystal clear on this issue,” he said in an email.

Nick was not one of the underage boys she is accused of assaulting, but those close to him say that it was his relationship with Forcier that ruined his life.

Although Highland Shores denies any wrongdoing, Facebook messages allegedly sent between Forcier and Nick — and seen by Global News — suggest an unhealthy relationship may have blossomed between Forcier and Nick, then 15 years old, while both were at the Children’s Aid-run facility.

Nick’s family and employees of the Children’s Aid Society claim Highland Shores investigated Forcier’s alleged relationships with the boys in her care. The facility closed soon after the allegations against her were brought forward.

While Annie says her son never claimed to have had a sexual relationship with Forcier, she is sure that her son was corrupted while under Forcier’s supervision.

“I definitely know Nick’s time around Sandy Forcier, he went down a dark road, darker than I ever, ever saw,” she said.

READ MORE: Children’s Aid executive facing 20 charges in child abuse case