Stay informed

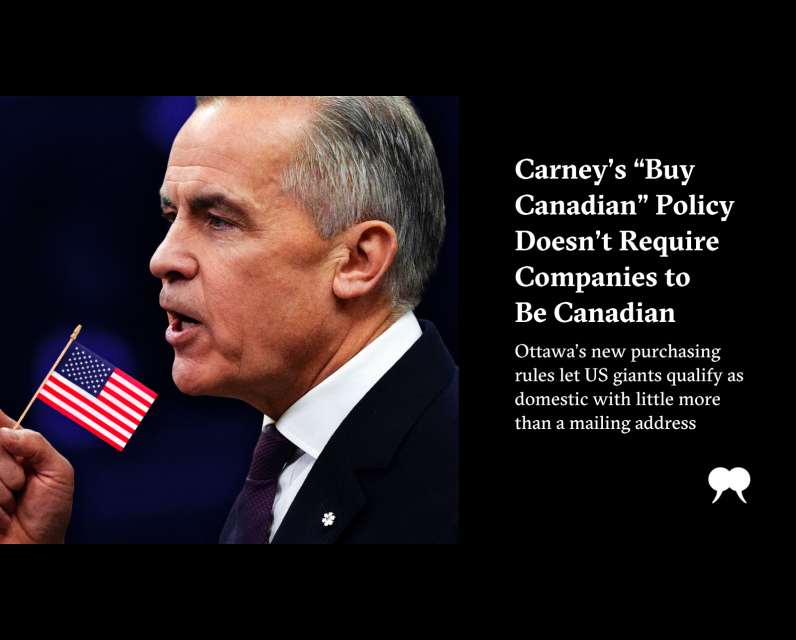

Carney’s “Buy Canadian” Policy Doesn’t Require Companies to Be Canadian

In recent years, Canada has conducted major Arctic exercises to reinforce its sovereignty over the North. Those operations tend to reveal the same fragility: specialized equipment dependent on foreign manufacturers and logistics chains stretched across borders and oceans. The flag may be Canadian. The infrastructure, often, is not.

Prime Minister Mark Carney has said repeatedly that the future of national defence depends on building domestic capability and diversifying our defence partnerships. We have made commitments to meeting our NATO defence spending targets, and we have signed onto Secure Action for Europe, part of the European Union’s massive arsenal build-up—widely seen as an attempt to break its reliance on American suppliers. The government had been making all the right moves—until the recent announcement of the Buy Canadian policy.

The first problem with “Buy Canadian” is definitional. Around the world, national sourcing regimes are rooted in three core principles: ownership, control, and intellectual property (IP). That is the standard used in the United States and Europe to ensure that equity value, talent, and strategic know-how stay within national systems. Yet Canada proposes to depart from these norms.

The new policy means Canada will allow foreign-controlled multinationals to qualify as “Canadian” simply by running revenue and some employment through a local subsidiary. Take General Dynamics Ordnance and Tactical Systems. With plants across Quebec, it dominates the production of bullets, shells, missiles, and explosives in Canada. But the firm is American. The policy thus invites the very gaming it is supposed to stop. If this approach persists, a Canadian mailing address will be considered as important as who owns or controls the company. The result will be a system that continues to bind us to foreign allies rather than supporting and growing our own.

The second issue is financial signalling. Instead of placing capital directly with companies building core IP or seeding private venture funds capable of scaling dual-use Canadian technology or industrial capacity quickly, Ottawa appears intent on loaning money through Crown entities like the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC). The BDC model has, in the past, offered long-term, zero- or low-interest loans, often contingent on companies matching the funds. These are not revenue-bearing contracts. They are not procurement decisions. They are balance sheet liabilities that do not really grow a domestic industry.

An early-stage defence company does not struggle because capital is unavailable; it struggles because defence companies have only one customer—the Department of National Defence—and if they are not buying, there is no business. These Canadian businesses need purchase orders from their own country first, and that will give them the opportunity to scale on their own and build export plans. If Canada does not buy from them, it is hard for a Canadian defence company to convince allied militaries to buy.

Cheap loans do little for companies attempting to develop autonomous systems, advanced energies, Arctic communications, or aerospace platforms—areas where Canada needs sovereign capability. In those sectors, what matters most is that the government is willing to buy something. A purchase order tells global investors that Ottawa has conviction. A long-dated, zero-interest loan tells those same investors that Ottawa is waiting to see if someone else moves first.

This branch plant–mailbox definition combined with a loan-based support regime creates a system that looks busy but does not seize the moment. It amounts to doubling down on the failures of Canadian defence procurement in the past and shows a remarkable lack of confidence in our innovators and industrial base.

Ottawa isn’t blind to the stakes. A new defence industrial strategy is expected soon, and in broad strokes, the Carney government has correctly identified the need to rebuild national capability. The instincts of this new government are admirable, but their execution will not achieve their ambition.

We will still need the subsidiaries of foreign defence companies to manufacture and source supply chains in Canada, and we can be thankful for the critical work they have done for our military. From CF-18 fighter jets to the light armoured vehicles that saved lives in Afghanistan, our military will continue to rely on exceptional American suppliers, but it does a disservice to our country to describe these American companies as Canadian simply because they employ people here.

Canada has a choice to make. It can treat defence industrial development as simply a jobs program—an exercise in incremental hiring and regional distribution—or it can treat it as a strategic exercise in building capability measured in ownership, IP, and export power. One path produces short-term benefits and long-term dependencies. The other produces sovereignty and optionality for Canada in an uncertain world.

The Carney government knows that sovereignty is not simply declared: it must be built and defended over time. It is time for Canada to build.

The post Carney’s “Buy Canadian” Policy Doesn’t Require Companies to Be Canadian first appeared on The Walrus.

Comments

Be the first to comment