Unpublished Opinions

Lynn is an Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe from the Ottawa River Valley, Ontario, Canada. She describes herself as a learner-researcher, thinker, writer, Black Face blogger, and she has been an Indigenous human rights advocate for 25 years. Lynn works to eliminate the continued sex discrimination in the Indian Act, and she is also an outspoken critic of the contemporary land claims and self-government process. She has a doctorate in Indigenous Studies, a Master of Arts in Canadian and Native Studies, and an undergraduate degree in Anthropology. She also has a diploma in Chemical Technology and worked in the field of environmental science for 12 years in the area of toxic organic analysis of Ontario’s waterways. While advocating for change is currently part of what she does, she is also interested in traditional knowledge systems that guide the Anishinaabeg forward to a good life.

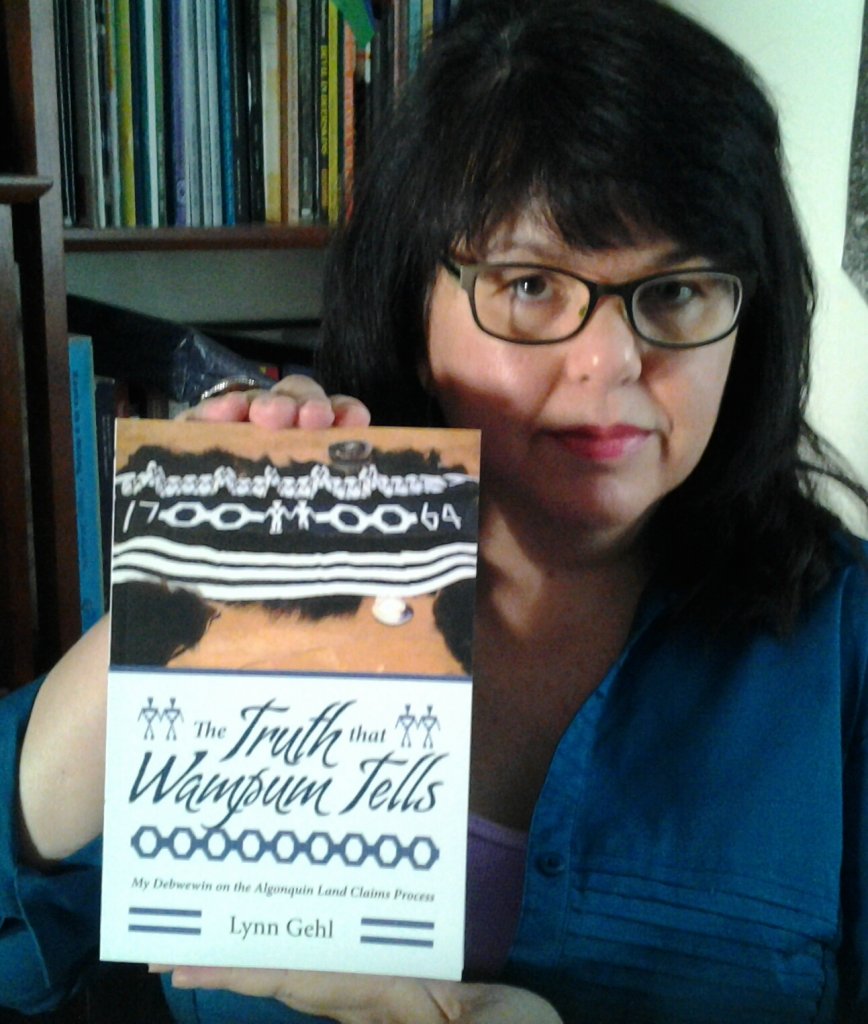

Along with many journal and community publications, she has three books:

Anishinaabeg Stories: Featuring Petroglyphs, Petrographs, and Wampum Belts

The Truth that Wampum Tells: My Debwewin on the Algonquin Land Claims Process

Mkadengwe: Sharing Canada’s Colonial Process through Black Face Methodology

Shkaabewis are Genuine “Helping People”

Who is film maker Andrée Cazabon?

Who is lawyer Michael Swinwood?

Who is the group Free the Falls?

Who is the group Stop Windmill?

The Algonquin Anishinaabeg are in pretty dire conditions. We have never had a treaty and our nation has been divided by imposed British and French laws, imposed English and French language, and imposed religions, as well as imposed provincial borders. The situation of the Algonquin was largely accomplished through do-gooders also known as people with so-called good intentions. One example is the residential school system imposed by Canada and the churches. Another example is and continues to be “helping” Indigenous people become more civilized through the land tenure system. In addition there are all the earlier anthropologists who were actually agents of the state.

Through decolonization and Indigenous awareness of these do-gooder agents of the state, and the birth of theoretical frameworks such as feminism, critical theory, anti-colonialism, allyship, and more recently Indigenism many people are now asking tough questions about people who come in to our communities claiming to be a helper.

Being a shkaabewis or in English "a helper" is a place of honour and a place of humbleness where it is now expected that they must tell us: Who are they? Who are they related to? What do they want? Why do they want it? How did they determine and define the help they seek to offer? Who is funding their efforts? How do they plan to meet our needs? What are their unstated political affiliations? What is their strategy? Who are they accountable to? How will they allocate funds the process may generate? How are they assuring that friends have not biased them?

Asking these questions is now the accepted way to protect community members and assure the community’s needs are paramount, but also as a way of assuring that the effort being taken is indeed genuine and legitimate. In terms of the latter, if the effort is not viewed as legitimate community support for the effort and the mobilization of the effort will be hindered. This would be counter-productive to the goal.

Contrary to what many may think I ask these questions not to be harmful. Rather, I ask for valid reasons. I ask because I want the larger Algonquin Anishinaabeg to be able to trust these people if they are indeed worthy, and I also ask these questions as a measure to assure what they are doing is a good thing. As I have said legitimacy is important. If Algonquin do not see the person or the effort as legitimate this is not a good thing. If these helpers are genuine they will appreciate the need to assure that their role and effort is genuine and legitimate. In short, they will value the questions.

We have all heard of, and many of us personally know, individuals who come into our families and into our communities offering us help, such as giving us their services, time, shelter, food, clothes, and money. Unfortunately, what some of these “helping people” count on is for members to be too busy where as such they are unquestionably grateful for the help being offered. This is the ultimate form of vulnerability. As a result of the great need, and the imposition of the survival mode imposed on them by Canada, many of us cannot stop, think, and ask these hard questions. But, some can and this is a good thing not a bad thing.

Poor families and Indigenous communities are particularly vulnerable. We all know this and so do others. Even today our families and communities continue to be infiltrated by outsiders who are selfishly seeking research needs, the need for a spiritual experience; the need to be perceived as a good person; and there are people who want to sexually exploit the exotic and young girls and boys, persons with disabilities, the elderly, sometimes even babies.

As suggested helpers are not limited to what is obviously evil. Some are sociologists and anthropologists; where others are reporters, journalists, and media and film makers. They are all looking for their stories to fulfill their own needs. Still further, others are activists, both charitable and social. But of course the worst are the pedophiles. There are also the land claims and legal industries where people are seeking and gaining huge financial rewards and/or media fame in the realm of legal precedent from the Aboriginal law industry. They all want something, some more sinister, some less sinister. Our Needs Matter More!

The point is, Indigenous families and communities have been the fodder of much questionable practice. Fortunately, academics are now more ethical in their research where many, if not all, now allow us to shape the research process, its goal, and the direction of the knowledge produced. But there is more work to do in our journey forward to liberation, freedom, and self-determination. Indigenous families and communities need to put in place within our minds and practices the confidence that we do indeed have the right to ask hard questions.

If they are genuine people with integrity they will be respectful of our need to know the answers to these questions, and they will appreciate that they need to be transparent on these issues and respect our need to know. We have a right to protect our communities and assure all political and legal actions are legitimate and will be perceived as legitimate.

When helping people respond to our questions in a way that implies they are insulted and possibly say things such as: “I am volunteering my time, be grateful”, or similarly with “No one is paying me, be grateful”, these are individuals who are not deserving of the privilege of being “helping people”. Another more disturbing response is they may move into a character attack or assassination of the person who has taken on the hard job of asking the questions. The helping person who takes this reactionary response should be avoided.

To be a Shkaabewis is a place of honour and humbleness.

Please like and share this blog post. Chi-Miigwetch!

Comments

Be the first to comment