Unpublished Opinions

Clive Doucet is a distinguished Canadian writer and former Ottawa city councillor. He was elected for four consecutive terms from 1997 to 2010 when he retired to run for Mayor. As a city politician he was awarded the Gallon Prize as the 2005 Canadian eco-councillor of the year. He was defeated twice by Jim Watson in 2010 and 2018 when he ran for the Mayor’s chair.

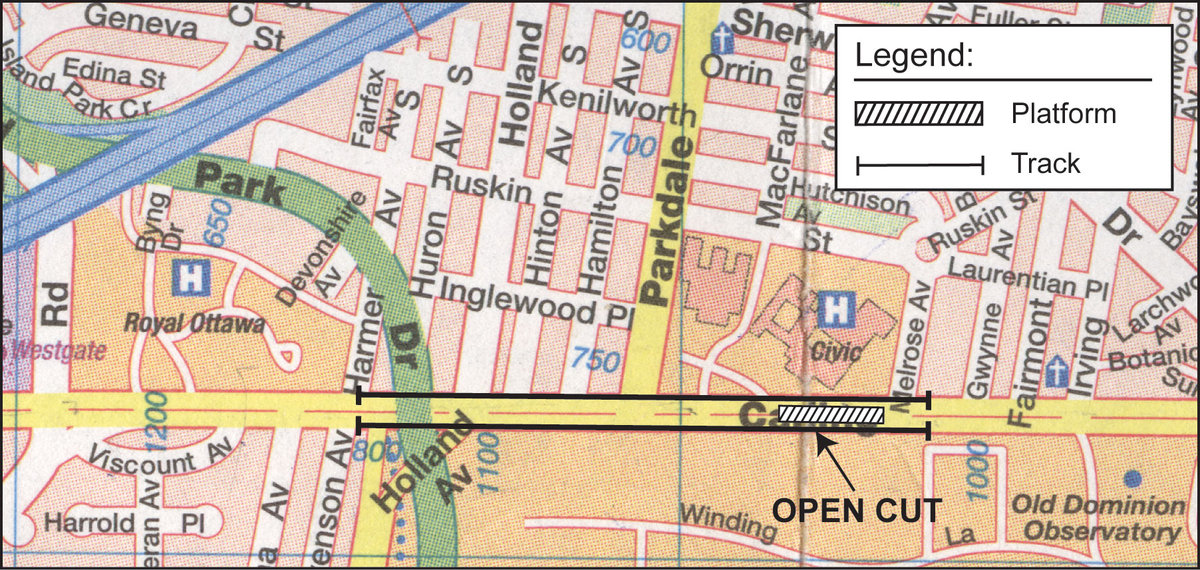

Carling Avenue LRT Concept Design Study

Here is one of the reports that Councillor Christine Leadman and I worked up during our shared tenure on council, 2006-2010. Our proposal was always that the only western connection that made any sense was Carling Ave. Presently, it is a failed urban arterial, six to eight lanes wide of underused roadway all the way to Kanata. With the proposed expansion of the Civic Hospital it makes more sense than ever as the western trail route. It has two hospitals, many shopping centres and about 300,000 people along the route. Plus it gives a much quicker access to the airport than the seagull route which is already served by the bus transitway and connects to nothing but the river front and some expensive condos..

I see critics of Carling Avenue complaining that it has 28 cross streets. Why does it have so many cross streets? Most of them are underutilized and traffic could be very easily re-directed to a smaller number. The cross streets that remain could easily be dealt with as Calgary has with its C line. The C line has worked for 40 years down the centre of a very similar arterial and employs simple barriers which descend as the train approaches. There has never been an accident that I know of. A couple of the more difficult Carling intersections could easily dealt with small underpasses. We did a good deal of work on the Carling proposal and I have confidence in this Concept Design Study.

- Rationale for Carling Corridor

- Implementation Issues

- Network Integration

- Operations Concept

- Capital cost

- Maintenance Facility

Why Carling Avenue?

Professor Richard Soberman commented many years ago that transit users in Toronto did not actually want a few high density transit corridors (subways) but would prefer a medium density corridor network, given a choice. The access and service levels provided by medium density networks are superior to high density corridor operations. Medium density corridors are characteristic of London and Paris which are not high density cities for the most part. Ottawa is a medium / low density city. This study addresses the Carling Corridor in that context.

Characteristics of the Carling Avenue Corridor:

- Carling Avenue was identified by the Peer Review Panel convened by the City in May 2008 as a priority element of the ultimate network. It is the artery for an area of Ottawa which is a combination of commercial, retail, medical and adjacent residential development. Re-development along Carling is evident and would increase significantly if a fast and convenient connection to the central business district (CBD) was available. From a public transit perspective it has a multiplicity of activity centres all of which generate high volumes of people movement throughout the day:

- There is a significant employment generated in the corridor: public sector (Booth / Rochester area and hospitals), retail (shopping centres), medium-rise office complexes.

- Two major hospitals and a series of medical centres (all of which have parking capacity and cost issues).

- The three major shopping centres are all directly on Carling Avenue.

- A concentration of high-rise apartment blocks between Woodroffe and Lincoln Fields.

- The street allowance of Carling Avenue, and the centre median layout are compatible with a surface operation in a segregated median right-of-way. This will provide a western LRT corridor at lowest capital cost.

- An efficient interchange with the BRT system (at Lincoln Fields) will provide good network connections for passengers.

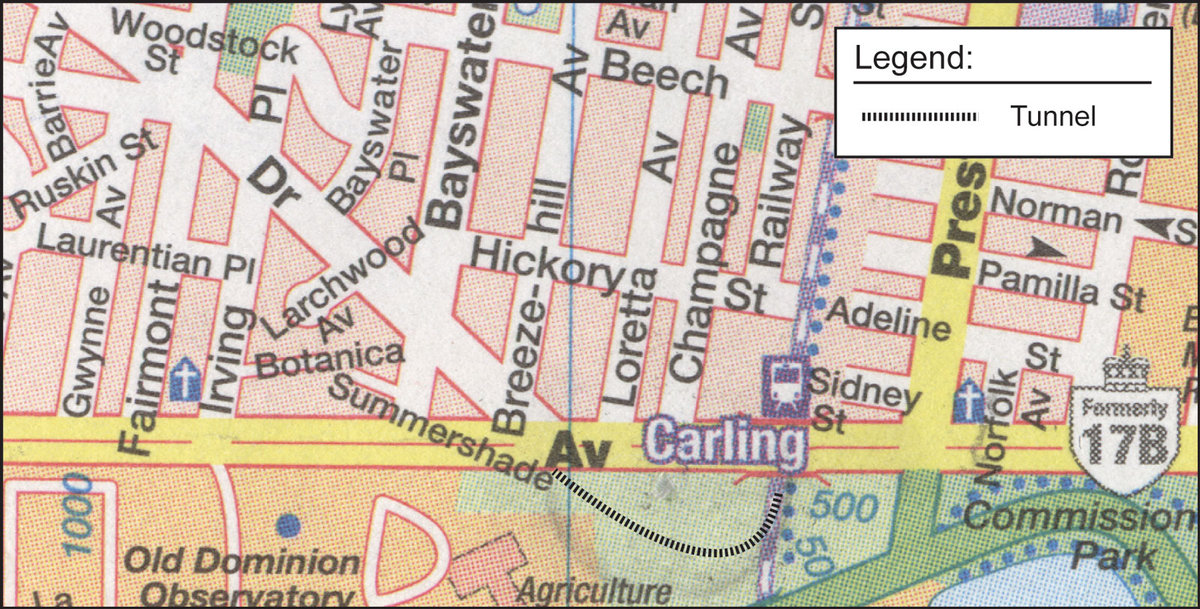

- A junction with the N-S line immediately south of the present O-Train Carling station (by a short tunnel under the NCC parkland) will provide a through route to the CBD. It will also provide access to the maintenance facility at Bowesville.

- Bus feeder services from the adjacent residential areas can be provided efficiently and cost-effectively due to the north-south arterial street intersections.

Conclusion: In almost all respects the Carling Corridor offers the desirable attributes which would justify a significant transit infrastructure investment. It is particularly worth noting that LRT service along Carling would attract development compatible in location with an efficient transit operation - the primary objective of transit-oriented development.

1. Why LRT for the Carling Corridor?

Rail transit is attractive to the public and to development investors alike. The worldwide examples (London, Paris, Berlin, Charlotte, Dallas, Vancouver, to name a few) confirm:

- The permanency of rail provides the confidence required for long-term investment.

- Rail system capacity can be expanded to meet increasing passenger demand by the exploitation of signalling and control rather than additions to infrastructure.

- LRT is more comfortable and dependable than buses, especially in winter.

- LRT is environmentally desirable due to lower emissions and noise.

- The operating economics of LRT are significantly better than buses. A large bus can carry 100 passengers at a cost of approximately $80 per hour whereas a double-articulated LRT can carry 250 passengers at approximately $125 per hour. (Multiple-car LRT trains are even more cost-effective.)

Toronto is a classic example of the effectiveness of rail transit in shaping development:

The picture above shows Yonge Street from St Clair north to Eglinton Avenue by the early 80’s. Each cluster of high rise is located around a transit station. There was nothing higher than a few stories when the subway was built in the early 50’s. Note the compatibility of low-density residential and high-rise development. Effective planning control has preserved the gracious older neighbourhoods.

The picture below shows the same area ca. 1952 when the first subway line was under construction. The white scar is the open-cut tunnel construction in progress. Note the street-cars which even at that time were contributing to traffic congestion.

2. Why not street-cars on Carling?

The enthusiasm for street-cars is a carryover from history. When street traffic was much less than today the street-car could function reasonably effectively, but that time is long gone. In the street-car era construction costs were significantly lower than the cost of any rail system today (of course the same is true for busways – the major costs lie in the acquisition of right-of-way, not the technology). Operating a $5 million vehicle, designed to run at 80 km/hr, in street traffic at 20 km/hr makes no sense at all. If traffic is the limiting factor in productivity then a bus is a much more appropriate solution.

Unless there is a clear right-of-way, and a minimal number of intersections and station stops, the cost-effectiveness of the street-car is unreasonably low. Safety is also a consideration because the stopping distance of a street-car is longer than that of a car or truck and the street-car driver cannot anticipate the actions of the car drivers. Collisions are frequent in street-car operations. At a minimum the street-car tracks should be protected by raised curbs to prevent intrusion by other vehicles (i.e. a segregated right-of-way). Schedule keeping is no better than a bus in rush hour in mixed traffic.

The picture below of St Clair Avenue in Toronto illustrates the point.

The urban integration concept of street-cars in pedestrian malls is perceived by some as the pinnacle of transit concepts. It is appealing but inappropriate for LRT. The safety concerns are obvious from this photograph of the San Jose system. The objective of a pedestrian mall is to preserve the freedom of movement, however this can also reduce pedestrian vigilance (especially in an age of MP3 players), as the rail vehicle runs very quietly at low speeds.

The Carling Avenue application is a rapid transit corridor. A segregated operation is essential and appropriate for service quality and reliability, especially when Ottawa winter conditions are taken into consideration.

The picture below shows the low-level boarding and designated median right-of-way in the Houston CBD. Despite road markings the lack of a raised curb has permitted auto collisions.

3. Carling Corridor LRT implementation issues

- Two of the features of Carling Avenue are that the median boulevard blocks all but a few secondary street crossings and that the road allowance provides adequate width for a median track location. Additional land take will be required in a few locations, and there may be a loss of one road traffic lane in some sections. There are 21 traffic signals between Champagne Avenue and the Lincoln Fields BRT station and one unsignalled road crossing. Traffic signals are clustered at:

- Woodroffe North/South - Carlingwood (4 closely-spaced signals),

- Westgate Shopping Centre (3 closely-spaced signals),

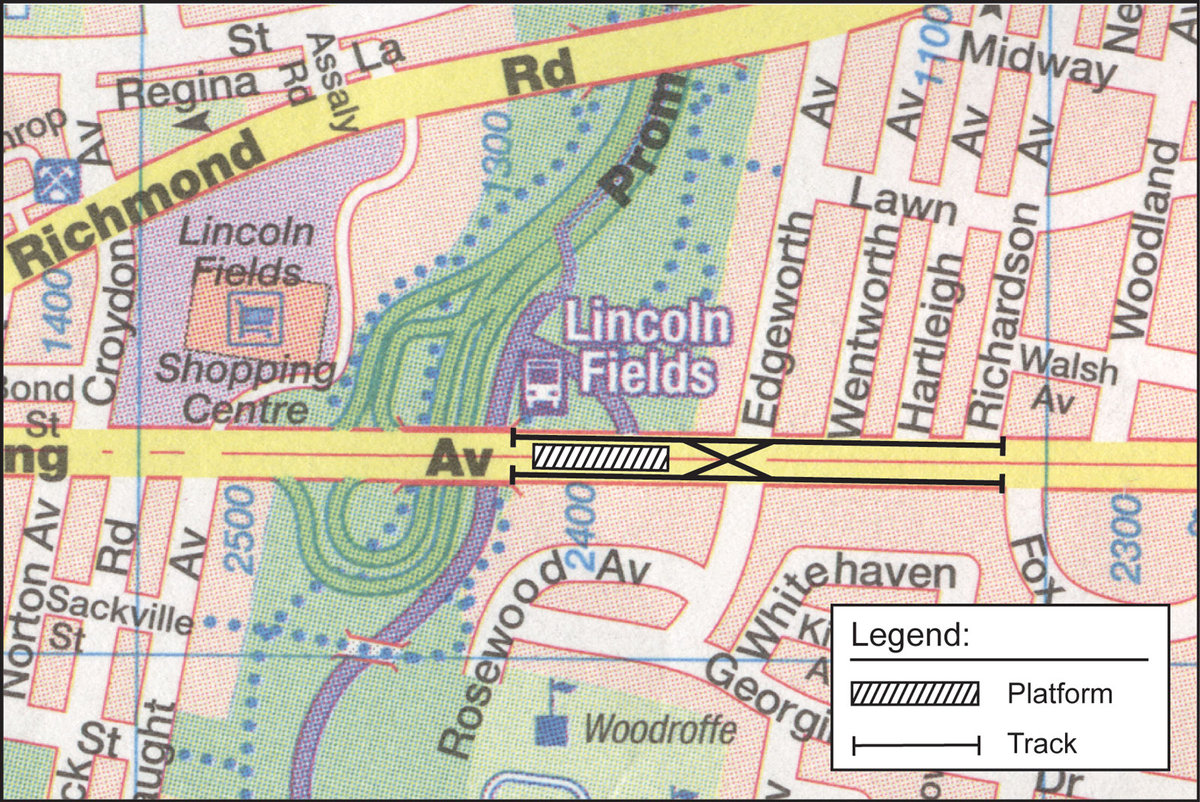

- Island Park-Holland-Parkdale-Civic Hospital (4 closely-spaced signals).

- Each of these clusters of traffic signals can potentially be handled by co-ordinated, pre-emptive signal control except for the Island Park-Holland-Parkdale-Civic Hospital zone which will require grade separation due to the road layout and traffic congestion. Several of the other crossings are close enough to be treated as pairs by locating stations between them on the far side of intersections to avoid left-turn lane interference. The simplification of traffic signal interference will aggregate 10 locations of which 7 will be stations. The one unsignalled road is proximate to Fisher and the Island Park crossing and could conceivably become a T-intersection on the Carling Eastbound carriageway.

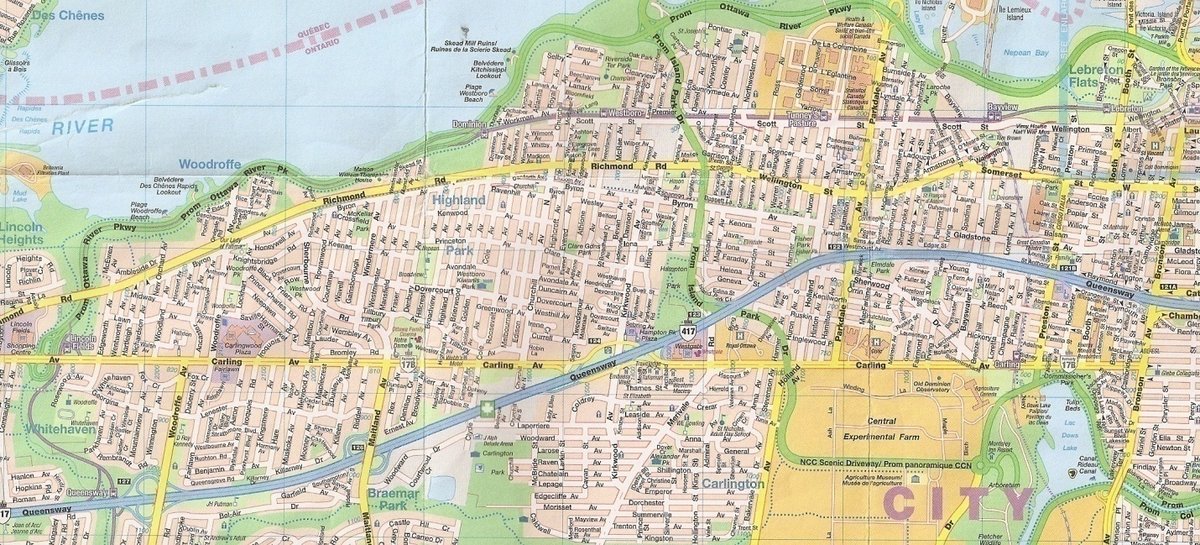

- The LRT requires an alignment as direct as possible across the 417 at Kirkwood in order to maintain a high average speed and to minimize traffic controls on Kirkwood. (Tracks in the Carling Avenue carriageways are not desirable for this reason.) The preferred alignment is an underpass through the 417 embankment between the Carling overpass structures from the median on the east side crossing Kirkwood to the area behind the fire station and headquarters complex. The westbound ramp to the 417 presents a challenge which can be overcome by starting the ramp further east to provide clearance for an LRT underpass. The LRT tracks will then be in line with the Carling median to the west.

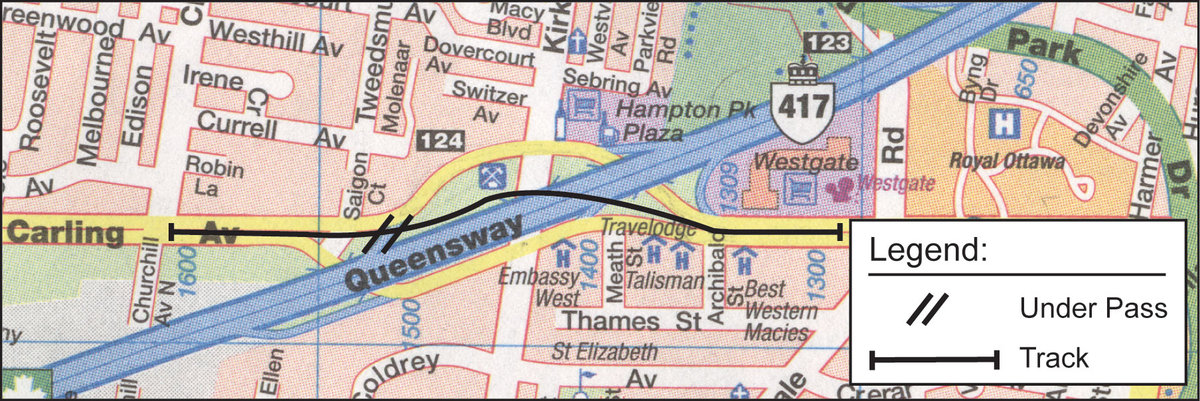

- Since the LRT will continue west from Lincoln fields at a future time the optimum location for the western terminal will be in the median opposite the existing entrance to the Lincoln Fields busway on the north side of Carling. The available road width can accommodate a centre platform and tracks. The trains will use a track crossover to enter and exit the station.

- The current Woodroffe N-S alignment at Carlingview will create a problem for vehicles traversing Carling in the presence of LRT median tracks and a station at Carlingview. A redesign of the intersection will be required to provide an efficient N-S crossing point with adequate lane capacity for waiting vehicles. Widening of Carling Avenue will be required.

- The Island Park-Holland-Parkdale-Civic Hospital network of crossings and surface space requirements can be separated from the LRT trains by an open-cut underpass. The rise in the ground level at this location partially compensates for the required entry and exit from the cut and will permit street level access to the stations at the Civic Hospital and Royal Ottawa Hospital / Westgate Shopping Centre locations.

- The junction with the N-S LRT tracks at the existing O-Train Carling station will require crossing the Carling eastbound carriageway and dropping down to the N-S track level by a curving tunnel under the NCC land to the south of Carling between Sherwood Drive and the N-S rock cut alignment. This will be done by open cut construction through the park which will then be restored when the tunnel is complete. The merge of the two tracks at the Carling station will provide same platform transfer between N-S and Carling lines, and access to the maintenance facility at Bowesville. The design of this junction will provide for the smooth interleaving of the two services by accommodating normal fluctuations in timetable operation.

It should be noted that the maintenance facility will be required 2 years in advance of revenue operation in order to commission, test and accept any part of the LRT network.

- A typical median station will have a level-boarding slab platform with passenger access from each side of the avenue at a pedestrian crossing which will normally be located at an intersection. The platform will be easily accessible by wheelchairs, prams or other wheeled devices. (Location shown is Portland, Oregon MAX LRT)

In summary, there will be challenges in the detail but solutions for all of the critical areas in the Carling median alignment have been identified.

4. Operations concept

An Operations Concept integrates the planning objectives with the practical options for running the trains such that the end result is convenient and cost-effective.

- The development of an Operations Concept requires a long-range perspective of the ultimate transit system configuration. It is clear that the interleaving of several services (East, West, N-S) through the CBD tunnel must be accommodated by any practical system operational plan. The completed Ottawa transit system network should provide for efficient transfer hubs served by BRT and LRT to maximize passenger capacity and destination choice.

- The Carling Corridor has the advantages described in part 1 of this study, the most important of which is the ability to link directly into the CBD by using the N-S line as part of an integrated network. This approach is the basis of the successful systems in Europe and Asia which create cohesive cities. (The N-S line also provides access to the maintenance facility).

- The integration with the Bayview BRT / LRT via the N-S line hub will provide for either efficient and timely single transfers from the East branch of the Ottawa network to the West branch or through running East – West. This flexibility will permit matching system capacity to daily demand fluctuations.

- Trains from Carling Avenue will access the Bowesville maintenance facility via the N-S line. The AM start-up, off-peak schedule changes and PM close-down will dovetail with the N-S operations.

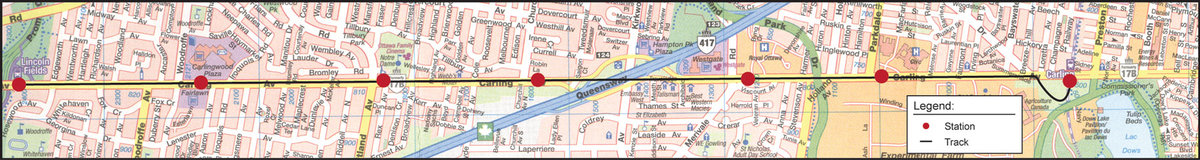

- For the Carling corridor LRT to be successful it must offer fast service in the peak hours. The average station spacing will be 1 km which will permit an average speed of 35-38 km/hr depending on the final configuration. The trip time from Lincoln Fields to the CBD will be 17-18 minutes depending on the CBD exit point. A maximum speed of 60 km/h has been assumed to conform to road traffic safety requirements. Increasing the maximum speed to 80 km/h results in an insignificant reduction in trip time. (Refer to Appendix B for the derivation of these data.)

- The Carling corridor passenger demand is not explicitly defined at this time but an interpolation from the 2006 study indicates a probable 6000 passengers per AM peak. This can be accommodated by a 5-minute headway which will permit track sharing with the N-S service from Carling to the CBD on a dual track between Carling and Bayview.

- The stations envisaged at this time are shown in the table below.

|

Type of station |

Activity centres served |

|

|

Lincoln Fields |

Carling Avenue median |

Shopping Centre, bus station, high rise apartment area |

|

|

Carling Avenue median |

Shopping Centre, medical centres, local residential |

|

|

Carling Avenue median |

Commercial, local residential |

|

|

Carling Avenue median |

Commercial, local residential |

|

|

Carling Avenue median |

Shopping centre, Royal Ottawa Hospital, commercial, local residential |

|

Ottawa General Civic Campus* |

Carling Avenue partially in cut |

Civic Hospital, medical centres, local residential |

|

|

Below grade transfer station |

Commercial, Federal Govt. Complex at Booth-Rochester, Carleton University and Federal Govt Confederation Heights campus (via same platform transfers to N-S line) |

|

|

Multi-level transfer hub |

BRT-LRT transfers |

|

CBD stations |

|

Entire downtown area |

(*Hospital access and parking costs are a major problem for many employees, visitors and outpatients. The provision of stations close to two major hospitals will benefit all of these groups.)

The spacing of the Carling Avenue stations harmonises with the basic planning criterion of a 400 metre walk-in access radius for the majority of passengers. The locations at major north-south arterial roads will provide for efficient bus feeder services from residential areas. The 2006 passenger demand study for the N-S service showed that the AM peak hour southbound passengers to Carleton University substantially exceeded all other stations including the northbound demand to the CBD. The transfer provision between Carling LRT and N-S LRT service can be expected to increase the Carleton traffic.

5. Capital cost

This cost projection is based on typical unit costs. No detailed design is available at this time on which a precise estimate can be based. The $ 460 million estimated cost includes:

- Carling Avenue road works;

- Traffic signals;

- 7 stations (slab plus shelter);

- Station E&M costs;

- Global estimate for water / sewer relocations;

- Tunnel at N-S line junction;

- Modifications to Carling station;

- Open-cut underpass at Island Park/Parkdale/OCH;

- Underpass at 417 crossing;

- LRT wayside system costs;

- LRV fleet required (incremental to serve Carling);

- Engineering, project management;

- Contingency; and,

- Property acquisition.

The total projected cost is which breaks down as follows:

|

Work element |

Est. Cost $m |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A previous study (dated 30.04.08) confirmed that the N-S LRT provides better value-for-money than an O-train upgrade. In order to maximize the cost-effectiveness of the integrated network this Carling Corridor cost estimate assumes the completion of the N-S line to enable full network access and shared use of facilities. The Bowesville maintenance facility will be required 2 years in advance of revenue operation of any LRT line in the network.

Appendix A Location of the Maintenance and Storage Facility (MSF)

The MSF is the location where planned maintenance cycles and exchange of major subsystems for overhaul and refurbishment of LRV’s are performed. Maintenance cycles occur typically at intervals from two weeks to ten years, depending on the accumulated kilometres of the vehicle. The elapsed time for such cycles varies from a few hours to one (for the major cycles possibly two) full shift. As much as possible the shorter cycles are performed during the day between peak service hours to maintain a high fleet availability and reduce night shift requirements.

Several sites were considered in a 2005 study. The location of the former Pepsi bottling plant on Belfast Rd. has now been added to these. The conclusion in 2005 was that the Bowesville site was the preferred location. When all factors are considered this recommendation still stands.

1. Belfast Rd. Site factors

a) Assuming the LRT East alignment will follow the busway from Hurdman to VIA the only apparent option for accessing the yard site would be to cross the VIA tracks at the east end of the station. There is a safety issue when crossing the VIA tracks. VIA trains depend on the train driver to stop the train - there is no automatic stop at red signals. The LRT trains can be safety interlocked to stop automatically when the VIA train is proceeding, but not vice versa. The stopping distances required by a VIA train (hence the safety distance allowance from the intersection with the LRT crossing) will be several hundred metres which would cause a significant delay to a waiting LRT train.

b) Assuming the LRT trains have successfully crossed the VIA tracks they now enter a single-ended yard (i.e. no exit at the east end). This is highly undesirable because any blockage of the sole access track will seriously interfere with maintenance operations and scheduling. A single-ended yard requires approximately 1.5 times the length of the storage tracks in order to transfer trains from one storage track to another, which means 300-350 m linear length of track (minimum) because of the track switching geometry required to move trains from one track to another. In contrast, the Bowesville site provided 8-car-length storage lanes which were accessible from both ends so that a failed train did not block the exit of healthy trains. A double-ended yard also enables the movement of trains into the maintenance building from either end of the storage tracks, thus reducing train movements.

c) If the Belfast Rd site were to be the maintenance (as opposed to cleaning and inspection) facility for the future fully developed LRT system it will require a building accommodating 6 tracks plus working space inside which implies a width of 70 metres plus the offices, workshops, parts warehouse, in addition to staff parking and bulk storage areas outside. The useful width of the building area will have to be at least 100 metres over the length of the yard. In addition to this at least 3 storage tracks (parallel to the rest) will be required for trains which are awaiting maintenance or are ready to re-enter service. The required total useable site width will be 150 metres.

d) When no programmed maintenance is required a daily cleaning and inspection track, parallel to the main line at the east end between Aviation Parkway and Blair Rd, would be sufficient.

e) The residences on the lanes off Tremblay Road will be very close to the active tracks of the storage yard. There will be an inevitable noise exposure to train movements on tight curvature tracks which will generate a noticeable level of wheel squeal. This will be more apparent at night when the ambient noise level has decreased.

2. Operational Factors

a) The full-build LRT system will include E-W and N-S lines. Bayview and Carleton University will be among the highest patronage stations during the peak hours. East line services are likely to terminate south of Carleton because the demand for no-transfer access to these stations from the east will be greater than the relatively small demand for through travel to the west. Running trains through from east to west will be a very inefficient ratio of vehicle-kms vs passenger-kms. Passengers from west Ottawa will use both express bus service to the Bayview interchange and Carling Avenue LRT for convenient connections to Carleton, Confederation Heights and the airport.

b) The termination of services at, or south of, Bayview at the end of the AM peak will facilitate removal of trains from service in the southbound direction and re-inserting them northbound for the PM peak.

Conclusion: The fully-developed system configuration should drive the MSF location. The site location and layout of the maintenance facility has a significant influence on the operating cost and operational reliability of an LRT system and should not be based on incomplete operational requirements.

Appendix B Derivation of performance

|

Derivation of Performance - 60 km/h max speed |

N-S line chainage |

stn spacing kms |

trip time |

station stop (secs) |

||||

|

|

||||||||

|

U of O - Bayview |

39.50 |

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

3.47 |

315.45 |

|

||||

|

Bayview |

36.03 |

|

|

15 |

||||

|

|

|

1.6 |

146.36 |

|

||||

|

Carling |

34.42 |

|

|

15 |

||||

|

|

|

1.2 |

91.67 |

|

||||

|

OCH |

|

|

|

15 |

||||

|

|

|

0.8 |

67.72 |

|

||||

|

Merivale - ROH |

|

|

|

15 |

||||

|

|

|

1.3 |

94.67 |

|

||||

|

Churchill |

|

|

|

15 |

||||

|

|

|

1.0 |

79.70 |

|

||||

|

Maitland |

|

|

|

15 |

||||

|

|

|

1.3 |

94.67 |

|

||||

|

Carlingwood |

|

|

|

15 |

||||

|

|

|

1.0 |

79.70 |

|

||||

|

Lincoln Fields |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Station platform approach and crossover @ 25 km/h |

|

0.2 |

28.82 |

|

||||

|

Total run time + station dwells |

|

11.8 |

1103.77 |

105 |

||||

|

Trip time-one direction (mins) |

|

|

18.40 |

|

||||

|

Turnback dwell (secs) |

|

|

|

300 |

||||

|

Round trip time (secs) |

|

|

2807.54 |

|

||||

|

Travel time Bayview-Lincoln Fields (mins) |

|

|

13.14 |

|

||||

|

Average speed (m/sec) |

|

|

10.67 |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Train performance assumptions: |

|

time to (sec) |

dist. to (m) |

|

||||

|

accn to break point m/s² |

1.0 |

|

|

|

||||

|

break point km/h |

35.0 |

|

|

|

||||

|

break point m/s |

9.7 |

9.70 |

47.0 |

|

||||

|

max speed m/s |

16.7 |

|

|

|

||||

|

average accn above constant torque limit m/s² |

0.7 |

9.53 |

127.4 |

|

||||

|

braking from cruise speed |

0.9 |

18.56 |

125.50 |

|

||||

|

total |

|

37.78 |

300.0 |

|

||||

Comments

Be the first to comment