Unpublished Opinions

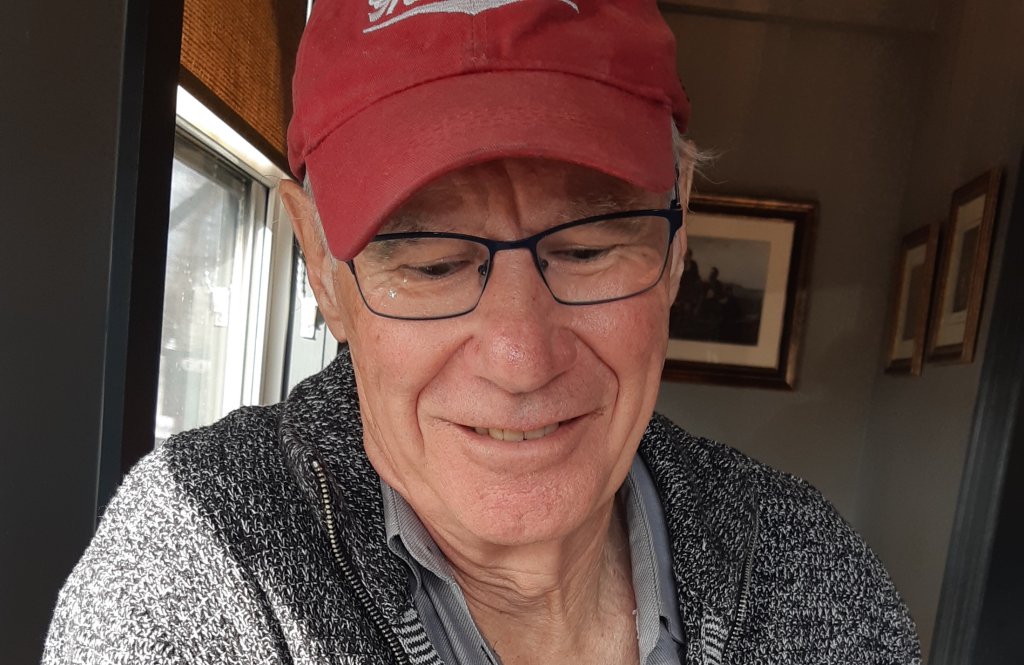

Clive Doucet is a distinguished Canadian writer and former Ottawa city councillor. He was elected for four consecutive terms from 1997 to 2010 when he retired to run for Mayor. As a city politician he was awarded the Gallon Prize as the 2005 Canadian eco-councillor of the year. He was defeated twice by Jim Watson in 2010 and 2018 when he ran for the Mayor’s chair.

The Watsonics, Part III (b): Amalgamation squashes democracy

“When two-tier local government was blended into one across Ontario, the greatest strength of local government, participatory democracy, was squashed.” –Clive Doucet

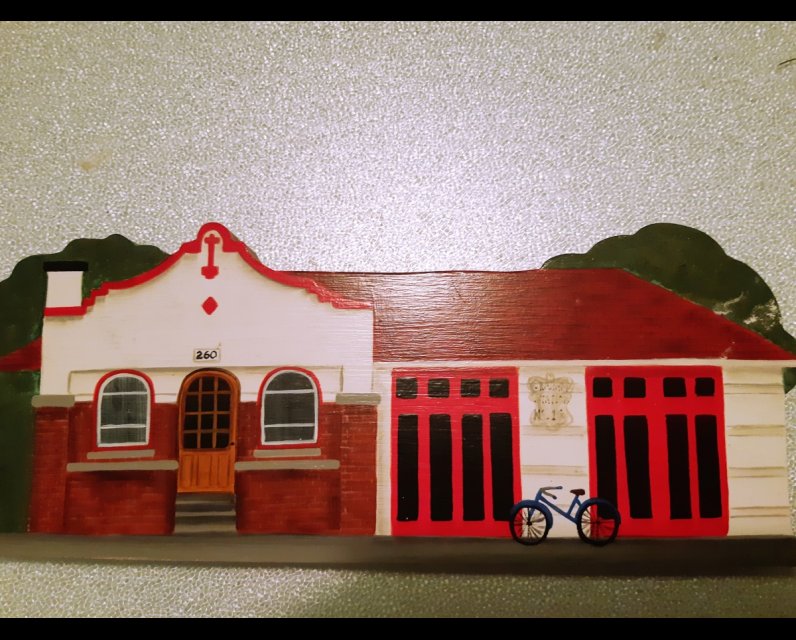

The first difficult issue that came at me after my election was similar to the Aberdeen, but much smaller beer. The City of Ottawa had decided it would like ‘to save money’ by selling off the city’s ward yards. These yards were small, fenced in workspaces often in the dead centre of a neighbourhood. The yards were used by the city’s maintenance crews for storing vehicles and equipment needed to maintain city streets, fill wading pools, trim trees and so on. The Ward Yard which concerned the Old Ottawa South community was directly adjacent to a busy community park called Windsor. The Community wanted it greened up and integrated into the park instead of being sold to developers for condos.

My first political act as a Regional Councillor was to put together a brief outlining why this city yard shouldn’t be sold ‘to save money’, but instead integrated into the park. With the President of the Community Association at my side, we went down to City Hall with petitions and documents in hand to make a presentation to Mr. Watson who had now graduated from ordinary city councillor to become the mayor of the old city. It was quite a moment for me. I wore my best duds and to my delight a city hall reporter interviewed me where I earnestly made the case for preserving city Ward Yards as public spaces. Then we entered the committee room with Mr. Watson presiding above us on a raised platform wearing his chain of office, looking very mayoral.

The mayor watched me approach the public table to make my presentation with some interest for it wasn’t a usual thing for a Regional Councillor to present at City Council. The Region had different responsibilities from the city, mostly based on scale. Region wide services, such as water, electric corridors, the largest green spaces, regional land use planning, regional roads and so on were our responsibility. Small scale stuff like community parks, recreation, neighbourhood streets, local road snow clearance, culture belonged to the local municipality.

Mr. Watson gavelled the meeting to order with the sound cracking out in the room. Papers in hand, I sat up straight ready to engage. Whereupon, the mayor said in a calm, but slightly bored way using his fine baritone to good effect. “This is a no-brainer. We should add this Ward Yard to Windsor Park.” He looked around for support from his committee, had it, the gavel hit with a crack again and it was over. Decision made and our delegation was dismissed without doing much more than announcing our presence for the committee clerk to record.

I felt a little foolish. The mayor treated the whole issue as if there never had been any intention to privatize the yard and our trip to City Hall had been a waste of time. His response was so effective that neither the Community President nor myself grasped that we had just been given a master class in news cycle management. The story of developers buying up valuable city ward yards for a song vanished in the media as if it had never happened. People in the community quickly forgot the mayor had any intention to privatize ‘their’ yard. So, did I. I was busy and like an unexpected bend in the Dumoine River, the little meeting at City Hall went out of my mind. What was there to remember anyway? Wasn’t this the way democracy was supposed to work? Your elected representatives propose, the people react, there is debate and a decision is made at City Hall. Hopefully in the community’s favour.

What none of us understood was the Harris government’s proposal in the year 2000 to amalgamate the regional level city government with all the other local governments in the county from the edge of Arnprior to Burritt’s Rapids hadn’t been designed to strengthen democracy but to weaken it. To prevent what had happened at the Cattle Castle and Windsor Park Work Yard protests from ever occurring again.

When two-tier local government was blended into one across Ontario, the greatest strength of local government, local participatory democracy was squashed. Under the Ontario Planning Act, people who live closest to city planning, housing, park projects, etc. are supposed to carry the most weight at City Hall, not those furthest away, which makes sense because it is the residents close by who will benefit the most or suffer the most from these developments. After amalgamation, the local voice would not just be reduced, it would disappear. People living beyond the Greenbelt, an hour’s drive from Lansdowne Park, east, south and west would decide that a mall was an appropriate use of the city’s oldest, most important park because in the new, amalgamated city, the local reps at City Hall would become stick figures with a voice but no authority.

I’d love to say I had all this figured out at the time, but I didn’t. Nonetheless, I did understand at a most profound level that the fight to save Lansdowne Park was a fight to save the city’s soul. If developer interests could privatize this historic, city landmark, then they could do anything. Nothing would be sacred in the suburbs or the city centre. Happily, I was not alone. The community put up a terrific fight. Led by June Creelman, the community took the city all the way to the appellate court in Toronto. They protested, sang songs, marched on city hall, donated money, hired lawyers. They gave it everything they had.

But we had no chance for the Lansdowne story was intertwined with this larger story of killing the political voice of the old communities across Ontario. On January 1, 2001, every single municipality in the old County of Carleton were blended into one. The new City of Ottawa would now be bigger than many countries, have a larger budget than several provinces, and would force together communities that had nothing in common except the profits and problems of sprawl. It would take a couple of years to accomplish the amalgamation but by my second term, I was now part of a single tier, one stop political shopping centre. The old city was gone.

Nothing in the Province’s inquiry into the mismanagement of the city’s LRT system has surprised me. The back door decision making, the hiding of information, the manipulation of the facts, etc. Because we saw this exact same behaviour during the struggle to save Lansdowne. I remember the Ottawa Sun ran a picture of the people’s plan for Lansdowne. Readers loved it but it was described as the developer’s plan, not the peoples. Misrepresentation had become as common as grass but this time I felt obliged to bring a motion to council to stop the proponents from running misleading pictures of their plans. Nothing changed. As with the LRT, Council was treated without the slightest respect. Council was a problem to be overcome, not a participant in city decision-making.

Amalgamation made all this possible. Democracy depends on community and amalgamation disconnected Ottawa communities geographically and politically from the people they elected. Initially, I had supported amalgamation. Why not have one police force, one fire service, one set of parks and so on? Why have the duplication? It was time to move on. The old city was too small.

The new amalgamated cities of Ontario would be based on freeways, malls and multi-story downtown condos. The old cities would become servants of this new urban vision of the future, which is called Texas High Hat. A Texas High Hat City from above or the side looks like a sombrero with a narrow but tall city centre spike surrounded by a vast brim of low-rise development. In a frenzy of city centre development, Ottawa would rip apart its old neighbourhoods and re-seed them with high rises while the size of the brim would explode.

The speed of the change has been amazing. It has all been done in the name of densification, which is supposed to be good for the environment. I don’t believe it is. I believe images of busy, friendly, denser streets often with streetcars running on them and little cafes beside them, have been used to justify ignoring community wishes and turning streets into parking lots with toaster boxes. Over-development now sits like a canker on the old city reducing the city’s quality of life and exploding under development in the brim. Sprawl is now at levels never anticipated by anyone. Ground water pollution is dealt with by just extending city pipes. The village of Russell, Ontario is now ‘on city water’. Densification like the promise of football at Lansdowne has been used by politicians and developers as a sound bite to make greater profits possible, not to serve the needs of communities or the environment.

During my tenure as a city councillor, I did not allow a single new building to be constructed that contravened the city’s zoning for height or density. My approach was simplistic. If the zoning law called for four or six stories on a busy street, it should be four or six, not ten or twenty, forty or fifty. I was happy to help a developer achieve this and did, but his plans had to conform to the city’s zoning. Either the law was the law, or it wasn’t. Turned out, it wasn’t. During the Watsonic years, city zoning has had about as much meaning as fish wrap. Even winning at the province’s appeal board doesn’t mean anything.

Diane McIntyre’s cottage/house on a narrow triangle of land, next to Central Park was torn down for a massive, lot-line to lot-line building that looks like a toaster with windows. Side lot, back lot and front lot trees have come down everywhere to make way for these ‘infill’ toaster buildings and condo high rises. Diane moved out of the community. The matriarchs were shunted aside.

Clive Doucet served as Capital Ward’s City Councillor from 1997 to 2010. He ran for Mayor twice in 2010 and 2018. His last book is Grandfather’s House, Returning to Cape Breton. The Watsonics is a nine part political memoir being published in instalments, here first on Unpublished.ca.

More in this series...

The Watsonics, Preface: A Hard Slap >

The Watsonics, Part I: Walking Through the Door >

The Watsonics, Part II: Looking Back >

The Watsonics, Part III (a): Battle at the Ol' Cattle Castle >

The Watsonics, Part IV: Grandfather's Farm >

The Watsonics, Part V: Reality Vs. Idealism >

The Watsonics, Part VI: Ottawa—A Reflection Of Ancient Uruk In Canada >

Comments

Be the first to comment