Unpublished Opinions

Clive Doucet is a distinguished Canadian writer and former Ottawa city councillor. He was elected for four consecutive terms from 1997 to 2010 when he retired to run for Mayor. As a city politician he was awarded the Gallon Prize as the 2005 Canadian eco-councillor of the year. He was defeated twice by Jim Watson in 2010 and 2018 when he ran for the Mayor’s chair.

The Watsonics, Part IV: Grandfather's Farm

“All happy families resemble one another, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” is the famous line which Tolstoy begins Anna Karina. He may be right about families, but I’m not so sure about childhood. I would put childhood this way. “All children are happy in their own way and all unhappy children are unhappy in the same way”. —Clive Doucet

I had a happy childhood but that doesn’t mean I had a childhood that would suit another child. Today for the middle-class children, summers are for camps, cottages, road trips and hang out time. My parents had other ideas. They sent me half-way across the continent to spend the summer with my recently widowed grandfather in a little Acadian village buried in the Cape Breton highlands. My father and mother thought this was a good way for their eldest child to spend his summer. Their thinking was I could learn French because everyone in the village spoke French and I would be good company for him. As they drove me to the airport, Dad said: “I didn’t pack the kites. You’re too big for this now. Help your grandfather around the barn.” Mother said: “Have a good summer.”

I have no idea what I replied but it never occurred to me to say: ‘No, I’m not going’. I got on the plane and flew off into the unknown. Did it ever occur to my parents it could have been terrible to live with a Grandfather who thought television was an interesting gadget or an Aunt who could wildly startle over nothing discernible like a horse hitched to a cart without blinkers.

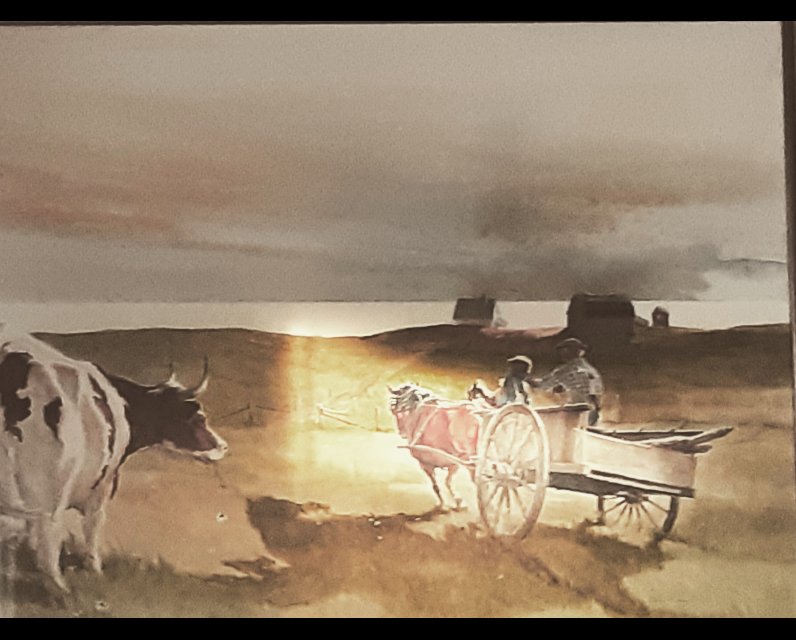

Grandfather’s idea of a good day was milking cows, making cream, feeding barn cats, splitting stove wood, and in the afternoon, he might hitch up the mare up and drive to the sawmill to see Uncle Gerard for some fence posts. This wasn’t exactly spiderman territory, but it suited me fine. The days spread before me from porridge, brown sugar and cream to supper and my aunt’s pan fried cod fish like big fat berries where every bite was delicious. Didn’t matter what we were doing or going it was all wonderful, including sitting on the sharp edge of a springless dump cart jumping like crazy over a rough field. I swear the old mare was smiling when I flew off.

Those summers changed my life forever, not just because I grew in confidence and affection but because they gave me a different idea of what life could be like. One that has followed me all my life. When I was a city councillor, my children sometimes thought I would have been more acceptable as a candidate for Mayor if I had been less determined to change the way the city was run. After I lost in 2010, Emma who had worked hard on my campaign, bringing her youngest to the office in a portable crib explained our loss this way: “People want Uncle Freddie for Mayor because Uncle Freddie can always be depended on for candy. Mr. Watson makes a great Uncle Freddie. They don’t want to hear the roof needs to be fixed.”

Mr. Watson certainly made a great Uncle Freddie, but I wasn’t driven by a nostalgia for streetcars and the small farms of my childhood. I was because they worked. Nostalgia is hearing the beautiful harmonies of the Mamas and Papas. I hear Cass Elliott wail into ‘California Dreaming’ and the present instantly disappears into memories of friends and smiles, and beautiful eyes that rise like bullets in the throat. That’s nostalgia.

The feelings I have for my grandfather’s farm are entirely different, more complex where the present does not disappear at all, instead those memories make the present more vivid. One does not cancel the other. Even as 12-year-old, I knew that my Grandfather’s farm could not go on. The conversion from the horse to the tractor even in highland Cape Breton was well underway. It just hadn’t driven the old ways entirely away yet. My grandfather would look at a neighbour cutting hay with a tractor much faster than he could with a team of good horses, shrug and say, ‘the day a man buys a tractor is the day the bank owns the farm.’

He was right but that didn’t stop the farms from getting so big, whole sections of the county disappeared back into bush along with the rural infrastructure which supported the small farms, the dairies, butchers, truckers until today barn milking parlours are serviced by milking robots. The dairy farmer today doesn’t even have to be present at milking time. The robots and cows can get along by themselves. The little farms fell like leaves from a tree in the autumn.

I’m convinced that climate change and the sprawl of urban meltdown got their start and continue to grow in the rapaciousness of ‘just-in-time’ supply chains which pumps cheap food across the planet much as oil is pumped in physical pipelines. This isn’t about nostalgia for another time. It’s about the consequences of shifting local and global economies to the present world of just-in-time delivery. It’s a world which is easy to disrupt and control. Real democracy shrinks because just-in-time delivery likes authoritarian government which focuses decision and makes it easier to control. Control the Mayor and you control the city. Authoritarian government also suits Russian oligarchs, Saudi and Texas oil sheiks, and Canadian grocery magnates. It also determines how we build cities and treat our own countryside.

The ship passing through the Bosporus from the Ukraine or Russia loaded with wheat and the one passing through the Panama Canal loaded with wine from Chili or bananas from Mexico needs 18-wheel trucks at the dock and Texas high hat cities with big box malls surrounded by fields of asphalt. At the production end, just-in-time global delivery has turned the developing world into plantation economies to service the richer countries. Less will understood is how just-in-time deliver has affected the first world landscape. It’s spread it out and enfeebled it.

When I was first elected in Ottawa, the first crisis we faced was the 1998 ice storm which destroyed the electrical infrastructure of eastern Ontario and Western Quebec. I learned two surprising things during that climate event. The first is that the private car doesn’t mean much. People can quickly learn to get along with out it. What cities and modern civilization can’t cope with is, no electricity and no 18-wheel trucks. Without long haul trucks people go hungry very fast, because no city has more than 3 days supply of food. Without the trucks, stores everywhere become empty fast. The other thing cities absolutely need is electricity. It’s a social version of blood. Without electricity the city’s most fundamental operations stop, starting with providing clean water and removing the dirty. Every city pipe system depends on banks of computers and massive pumping stations.

Without electrical blood, there is no mass transit, no emergency services, no restaurants, no heat in homes or public buildings. Without electricity, life quickly becomes insupportable. Putin’s generals have grasped this essential of modern life. You don’t need to bomb buildings, you just have to make them unusable. High rises are especially vulnerable. If the war expands beyond the Ukraine the focus will remain on shutting down urban electrical systems. It’s relatively easy to do and creates months of havoc.

At the end of the day, life is about how we chose to live together; and that depends on how we can imagine this is possible. We, the people, if we want, can imagine a different kind of city and a different kind of countryside because we’ve done it before and it’s worked. In 1960, more people per capita rode Ottawa’s streetcar and bus system than it does today after spending billions. The old Ottawa wasn’t magic. The city had a surface, rail system that served every part, that paid for itself and was entirely locally built and powered. It was torn up to serve the automotive industry. It didn’t have to be, and we can get it back. We can again create neighbourhoods where it is not necessary to jump into a car for anything, but a weekend jaunt. We can have farms which produce all kinds of fine food near cities, not an ocean away.

We can do this because it’s happening now in all kinds of ways. Today, we can imagine that a gay marriage is not only possible, but it happens. Mr. Watson grew up in a world where it didn’t. Times change and sometimes for the better. I am standing with city councillors Alex Munter and Elizabeth Arnold at the doors of City Hall. We are there to welcome the very first gay couple to be married in Ottawa’s new city hall. The unimaginable has happened and the world is a better place for it.

We need the unimaginable to happen for our entire society. We need to go back to the best of the old without abandoning the best of the new, but how do you do this when democracy itself has been defanged? This has been the great accomplishment of the Watsonic Years.

Clive Doucet served as Capital Ward’s City Councillor from 1997 to 2010. He ran for Mayor twice in 2010 and 2018. His last book is Grandfather’s House, Returning to Cape Breton. The Watsonics is a nine part political memoir being published in instalments, here first on Unpublished.ca.

More in this series...

The Watsonics, Preface: A Hard Slap >

The Watsonics, Part I: Walking Through the Door >

The Watsonics, Part II: Looking Back >

The Watsonics, Part III (a): Battle at the Ol' Cattle Castle >

The Watsonics, Part III (b): Amalgamation Squashes Democracy >

The Watsonics, Part V: Reality Vs. Idealism >

The Watsonics, Part VI: Ottawa—A Reflection Of Ancient Uruk In Canada >

Comments

Be the first to comment